By Antony Funell

ABC Australia

2019.Oct.11

Dutch marine architect Koen Olthuis has floated a novel idea. He wants to make the Olympics more affordable by staging them on water.

He predicts that would bring down the enormous infrastructure costs involved in staging the Games and allow poorer countries to bid for them.

The Olympics, he believes, needs to take on a bluer, not just a greener, tinge.

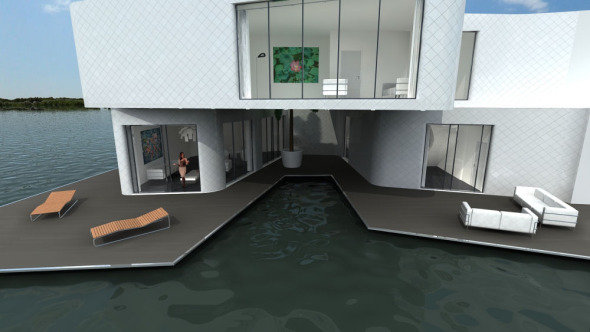

“You do it on water and you say, ‘We will build some floating stadiums and floating hotels and you can lease these structures for your city. And you use them and pay for their use for three or four months,’” Mr Olthuis says.

“Then they move to another city. It becomes much more logical.”

His vision might seem fanciful until you realise that the world’s largest ocean liner, Symphony of the Seas, already accommodates just under 7,000 passengers, and its length is the equivalent of almost four football fields.

So, engineering a floating hotel or stadium clearly isn’t a problem.

“In Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, we’ve already been active in designing these kinds of structures,” Mr Olthuis says.

“It’s more where do you place them, what kind of water you have, is it deep enough, what kind of flow is there, what kind of extreme weather you can expect.”

BECOMING LESS DEFENSIVE ABOUT THE OCEANS

The ocean-going Olympics is, for the moment, a thought experiment.

But it reflects a changing attitude among architects, engineers and urban designers.

“With improved technology we’ve found so many more ways that we can build into the sea,” says environmental scientist Katherine Dafforn.

That reassessment, she says, is being driven by the twin factors of climate change and urban congestion.

“We can’t easily remove those drivers, those stressors, so we do need to find a solution. And the oceans do offer some opportunities to find more space to house our population,” she explains.

Mr Olthuis believes the experience of the Netherlands can serve as an example of best practice.

The Dutch have traditionally viewed the sea as the enemy, he says, as a force to be conquered, but that’s now quickly changing.

“We live in a country where we shouldn’t live — it’s all beneath sea level. And now with climate change and a higher sea level we see it’s more difficult to keep our country dry,” Mr Olthuis says.

“So, we’re rethinking that and saying, maybe in some parts of Holland we should just let water come in and then start building on top of the water.

“WE SEE WATER AS AN OPPORTUNITY.”

A BOOM IN OFFSHORE ACTIVITY

The Queensland University of Technology’s Brydon Wang says that attitudinal change is beginning to transform our near coastal environments, with a wide range of vital urban infrastructure now being located offshore, especially energy-related facilities.

The Hywind floating wind farm is a prime example. It commenced operation 24 kilometres off the coast of Scotland in 2017. Its five massive turbines are 250 metres tall and are tethered to the ocean floor using giant chains.

They’re purpose built for resilience — to work with nature, not against it.

Hywind is one of around 50 floating wind farms currently planned or under construction in Europe.

Late last year it proved its long-term viability by continuing to generate power during hurricane-like conditions.

Mr Wang says the “natural moat-like environment of the sea” offers protection to such facilities. And the fact that they float provides maximum flexibility.

“For example, if you put a desalination plant in the ocean, you might have a situation where there is drought in a particular city and you can float that desalination plant to where it is needed,” he says.

That philosophy also appears to underpin the controversial development of Russia’s first floating nuclear power station.

It took more than 10 years to construct and began its maiden voyage in August.

Its role, according to Russian authorities, will be to service remote mining operations in isolated areas above the Arctic circle.

But this new focus on the oceans isn’t just about energy production or population expansion.

Mr Wang believes that by taking a “floating cities” approach, town planners can also enhance the cultural life of urban areas.

“One of the main problems with the way our coastal urbanisation has occurred is that we’ve got very flat and linear cities that are compressed against the coastlines, and that actually doesn’t make for very vibrant cities,” he says.

“If you look at Korea and Singapore they are starting to put immense cultural facilities in the water.

“Singapore has its massive floating stage that sits right in the marina. We’ve got a lot of cultural and exhibition spaces in Seoul that are floating in the nearby water bodies.”

FROM URBAN CONGESTION TO MARINE SPRAWL

Another way in which governments are choosing to deal with the twin difficulties of climate change and congested coastal cities is by “reclaiming” land from the sea.

Katherine Dafforn’s research, conducted with colleagues in Singapore, Italy and the US, suggests 450 artificial islands have been created in recent years to meet a whole range of needs — from military applications to tourism to airport construction.

Dr Dafforn also notes vast areas of the coastal marine environment have been walled off and filled in, with estimates that up to 25 per cent of Singapore is built on reclaimed land. For Tokyo it’s 20 per cent.

But China, she says, has been the most expansive.

“They’ve reclaimed extensive stretches of their inter-tidal zone. Around 13,000 square kilometres of their intertidal mudflats have been lost due to land reclamation,” Dr Dafforn says.

“I think that there is definitely a shift and more countries are actually investing money in doing it, even places like Monaco, places like the Maldives, all have their own plans for artificial islands.”

MORE STORIES FROM FUTURE TENSE:

But that trend, warns Dr Dafforn, risks creating “marine urban sprawl” every bit as damaging as its onshore equivalent.

“It needs to happen with some more sustainable ideas in mind,” she adds.

“The technology for building artificial islands has grown at the same time ecological understanding of the impacts and how to manage them has grown.”

She points to the Pacific where several artificial islands and structures have been created over coral reefs, resulting in enormous ecological harm.

“So, if we can put ecologists and engineers together at the beginning, when construction is first being planned and designed, then I think we have a lot of opportunities to build these artificial islands in a much more ecologically sustainable way,” she says.

Mr Olthuis believes architects and engineers need to embrace a double-sided approach to their design: thinking not just about what they build above the water, but also below it.

“For every project that we do we first have to do an environmental impact assessment. We measure the condition of the ecosystem before we do anything,” he says.

“We work with what we call blue habitats, these are structures that we connect to the underside of our buildings or our floating parks or whatever we do on water.

“And they have an effect on the water life — a habitat for fish, for green life under the structures.”

THE ‘BLUE ECONOMY’ — ENLIGHTENED OR EXPLOITATIVE?

The growth in interest in marine architecture and offshore engineering is now being described by the United Nations and others international organisations as the emerging “blue economy”.

An exact definition for what that term encompasses is hard to come by.

Even some of its proponents agree it’s a nebulous phrase which is being used to embrace everything from sustainable aquaculture to ocean-floor mining.

Darren Cundy from the newly-created Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre in Tasmania believes the label should only be used for activities with a sustainable edge.

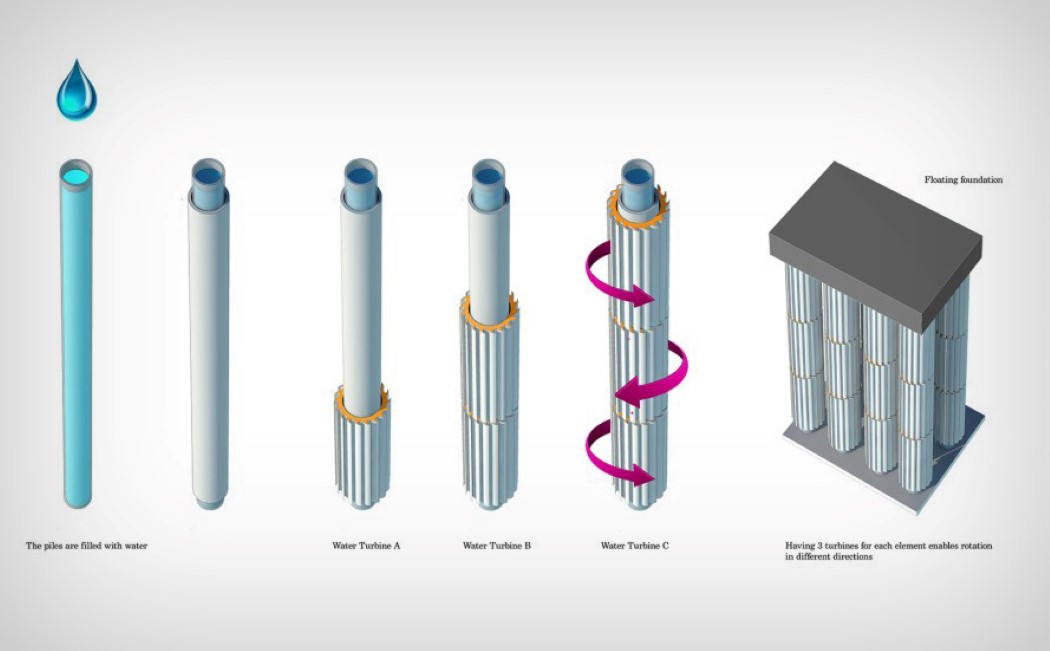

His $329 million project is researching the development of a giant floating fish farm. One that can also generate enough electricity to be self-sufficient.

“What really is clear is that the blue economy is challenging us to realise that the sustainable management of ocean resources is going to require a collaboration across borders and across sectors through a whole range of partnerships on a scale that really we haven’t seen before,” Mr Cundy says.

“The oceans are a vast resource and there are different perspectives on how the economic value of that might be tackled.”

But Fauna and Flora International’s Daniel Steadman worries about the veracity of an approach that tries to marry the seemingly contradictory aims of promoting environmental responsibility while increasing opportunities for exploitation.

“WHAT I FIND PROBLEMATIC IS THAT THE WORLD DOESN’T NECESSARILY WORK LIKE THAT,” HE SAYS.

“If you take rare earth metals from the ocean claiming that it’s because you’ll take less from the land, and then both the new extraction in the ocean starts up and the old extraction on the land continues, you’ve perpetuated a problem, probably created a new one, and not solved anything.

“Similarly, if you farm fish to reduce the need to catch them in the ocean, but then the fish in your farm need to eat fish from the ocean, you’ve created this sort of negative feedback loop of interdependencies where neither people nor the ocean are improving.”

The one thing that is certain is that as the world’s population increases exponentially — and as food, resources and space become a premium — more and more interest will be directed toward ocean resources, for better or worse.

Click here for the source website

click here for the pdf