By Evolve Arena & Björn Audunn Blöndal

Evolve arena

May.2018

The ocean might be the prime real estate of the future cities. This is what Equinor Innovation Team is set to explore in a series of expert workshops on the topic of floating cities.

The idea to explore Floating Cities at Evolve Arena in 2018 was initially brought by Anastasia Malafey, project leader at Evolve Arena in the meeting with Margaret Mistry, Strategy & Innovation projects leader at Equinor Innovation Team. Their common understanding that this can create new business applications and solve global urban development problem made them continue the dialog and turn discussion into action.

— For Equinor, the ocean space has been a massive source of value creation and competence building. Over the past 40 years, we have become the biggest offshore operator, we know marine operations, and we are a world leader on floating wind turbine farm market. Far from shore is where we feel close to home, says Anders Hegner Hærland, vice president at Equinor Innovation Team.

Equinor, formerly Statoil, have established Equinor Inovation Team to look into new business opportunities for the traditional oil and gas company. Its role is to explore and mature radical ideas and business model innovation. With a legacy stretching more than four decades back, Equinor, former Statoil, have drilled, built and run project both far out and deep into the sea. With high end skill, competence and a worldwide network of suppliers, Equinor is one of the companies most suited for being a major player in the arena of building the future of floating cities.

To kickstart a phase of exploration and learning Equior have invited companies, architects, engineers, urbanists and visionaries to a series of workshops. The workshops are facilitated by Xynteo and will be held in Equinors offices on Fornebu outside Oslo and other sites. The sessions are also live broadcasted to off-site participants.

— Building on our experience of the ocean as a commercial space, it still feels like a big step to the inspiring vision of Floating Cities. To most people, it might seem like a distant idea, but today major cities are running out of space to grow. Infrastructure is overloaded and quality of life for inhabitants diminished, Anders Hegner Hærland explains.

— The phase we are embarking on now is the exploration phase, says Margaret Mistry, Strategy & Innovation Projects Leader in Equinor Innovation Team.

— Evolve Team is grateful to see the high level of engagement and interest from Equinor Innovation Team, Xynteo and all partners involved. Now it is time for Equinor to step out of its comfort zone and become a spearhead and leading force toward new alternative applications of its competence and experience in solving major global challenges. We believe this explorational sessions and event at Evolve Arena give us unique opportunity to connect innovators, creative minds and industries and build clear momentum toward sustainable society, says Anastasia Malafey, project leader Evolve Arena.

— It’s an invitation to join us in exploring these possibilities together. Our conviction is that the technology, the commercial ideas, and the other ingredients for making floating cities a reality are within our grasp. But realizing them will require more than any one company can achieve alone. So we must begin with dialogue and collaboration, Margaret Mistry explains.

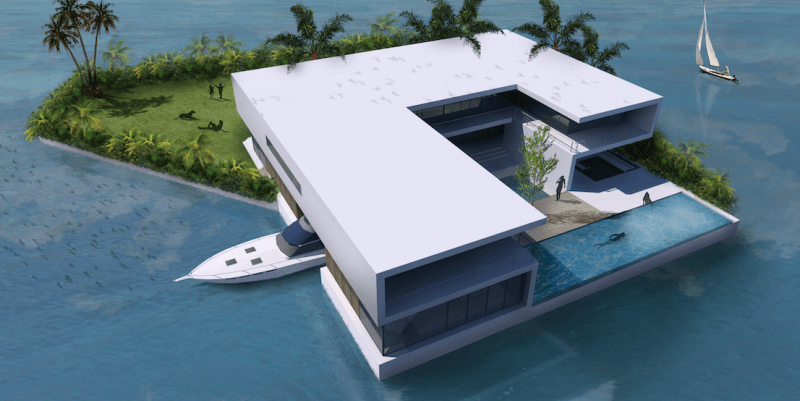

Floating cities represent a huge potential for urban development, food production, energy generation and minerals extraction on and under the water nearby coastal cities.

The first keynote speaker kickstarting the sessions is Koen Olthuis, visionary architect and CEO of Waterstudio, a dutch architectural firm that is set to develop solutions to the problems posed by urbanization and climate change. Olthuis compares the future of floating cities with smartphones populated with apps.

— Why can’t we use the cities like we use the smartphone? Why can’t we have floating buildings with different functions that we can move in and out as we need them — like floating city apps.

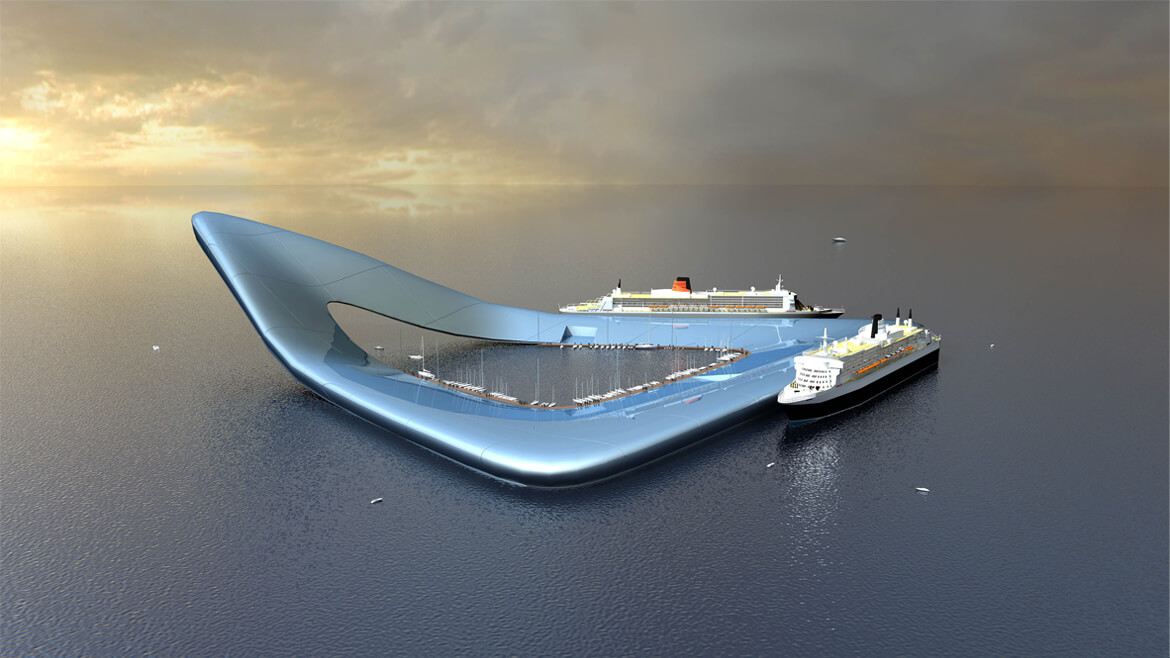

Olthuis elaborate how we can see projects as a service. Like for instance the Olympics, why do we build large stadiums and other facilities that is only used for a few weeks during the games? Why can’t we see expensive buildings like a floating stadium as a global asset that can be moved wherever the games are arranged? Qatar has already plans for renting huge cruise ships and connect them to a floating harbour and use them as hotels during the Olympic Games.

Blue Tech for Blue Cities

Building on water, done correctly, can also have huge environmental impact

Olthuis calls it blue tech for blue cities focusing on energy reduction, energy production and energy storage. As an example he mentions a breakwater project in New York that Waterstudio contributed in where huge rotating pillars serves both as breakwater, providing shelter and safe harbourage, as well as a dynamo, generating renewable energy.

Floating solar panels is another field of focus, as the global benefit of moveable panels would have enormous impact, and be of great value where electricity is needed.

Floating structures can also be beneficial for life at sea, both above and under the water. Olthuis have designed large steel structures based on existing offshore oil platforms. Built with layered floors with threes and plants above the water and aquatic plants under sea level, this can stimulate a wildlife oasis in urban areas.

— Oil companies have used these floating storage towers for years, we only gave them a new shape and function, Olthuis explaines.

To bring floating cities at scale we must move from pioneering, innovation and experimenting to standardization and regulations. At the same time we should take advantage of this phase of experimenting, because when things are standardized, the innovation will slow down, says Olthuis.

— Lack of regulation makes it simpler to experiment.

Olthuis emphasise that floating cities is not something that is happening in a science fiction future. Its happening now. There are several projects already in progress all over the world.

— Its not like we are building huge cities in the middle of the ocean. The first floating cities will be hybrid cities where part of the city is on the mainland and new facilities and functions are added on the water like an extension of the city. This kind of tech and mindset can change the structure of a city in a real short period of time.

In Desember Oslo will be the scene for a ground breaking exhibition and conference Evolve Arena on the theme of shaping the future of our cities. Equinor and Xynteo will host one of the side events workshops at the Evolve-conference.

— We will use the Evolve platform to host another creative work session with partners where we hope to emerge with a better understanding of where we can play a role and a unifying idea about the solutions that will bring affordable and viable floating cities a step closer to realisation, says Margaret Mistry.

Article deliver in collaboration with Björn Audunn Blöndal / PRESSWORKS

Cover picture: Floating harbor with cruice ships as temporary hotels by Koen Olthuis /WATERSTUDIO

Bron: Waterstudio

Bron: Waterstudio