By FuturARc

Jan. Feb. 2018

WATER WORLD

Groundbreaking solutions are being invented by forward-thinking architects to show how coastal cities can become more resilient, viewing climate change as an opportunity to lead the way in waterborne and floodresistant architecture.

Sea levels are rising to new highs, temperatures are increasing, and floods and storms are getting fiercer and more widespread. Climate change is not just about the risk of floods and drowning, but also the financial cost of damaged property and businesses; as well as how it will redefine which parts of a city are sought after and which are unsafe. A 1-metre sea level rise would reorganise maps and affect financial stability in many of the world’s biggest waterfronts, in cities like New York and Miami, and low-lying areas in Bangladesh, Vietnam and the Philippines. By resolving the issues stemming from climate change and urbanisation, water-based architecture is redefining urbanism. Offering a minimally invasive method of construction, modern floating developments take advantage of coastal zones, rivers, lakes and canals in spacestarved cities and provide flexibility as they may be modified, moved and reused until the end of their life cycles when they are recycled. The technologies and innovations required for water-based constructions already exist, but now changing the perception towards floating schemes is key to a more sustainable and safer future that will be able to meet modern-day challenges. What if instead of fighting rising sea levels, we embrace the water by integrating it into our cities, creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can deal with extreme flooding and heavy rains?

A leader in floating architecture who sees the potential that water can bring in making cities more resilient and safer, Koen Olthuis and his Amsterdambased firm Waterstudio (founded in 2003) have been showing the benefits of building on water and how befriending water is a means for survival. Olthuis believes that for centuries, as the climate and sea levels have been relatively stable, the resulting built environments have become too static. Now, with the arrival of uncertainty, cities should be designing with mobility and flexibility, viewing urban water as a chance to upgrade cities rather than a side effect. He states, “We are at the tipping point of entering the next kind of city. We have now the static modern city, but in one or two years from now, we’ll see that the green city will flourish. Then the next city to start will be the smart city with autonomous cars and more data availability—all to create a better city. But we are even one step further. We believe in the rise of the blue city. Cities that are next to, connecting to 1 or have water will start to use that water to create

cities that are more flexible, responsive, adaptive and built to change. So if there’s a need for cities that react to the seasons, that are different in winter than in summer, we can do it on water. We can do it better on water than on land because on water, everything is flexible and you can move complete

urban components.” Dynamic hydro-cities adaptable to changing needs should already be letting water in and making it part of the city, so that rising sea levels or storms would mean living with a bit more water instead of a sudden shock when conditions go from dry to flooded.

To plan for the future, a resilient city should concentrate on which areas should be kept dry, which can be changed from dry to wet, and which existing waters can be expanded; it is all about fighting water with water, wetting up the city. At-risk cities have to make the choice to become climate refugees or adopt floating technologies and become climate innovators.

NEW YORK CITY

New York has few flood protections, but that will soon change. In 2012, Lower Manhattan flooded and was left in the dark during Hurricane Sandy, with the greatest extent of inland flooding along the borough’s eastern edge, costing the public billions of dollars. Floodwaters up to 3 feet deep not only inundated the East River Park esplanade, ball fields and plantings, but they also crossed FDR Drive, enveloping streets and buildings. It was following the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Rebuild by Design competition in 2013, seeking new ideas for improving coastal resiliency in the Sandy-affected region, that a proposal led by Danish architectural firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) came about. Dubbed the BIG U, it called for separate but coordinated plans for three contiguous sections of the East River waterfront in Lower Manhattan named compartments, in close coordination with residents, stakeholders and city officials.

Architect Bjarke Ingels states, “The BIG U focuses on Manhattan to address the question: how can we create 10 contiguous miles of flood protection without creating a sea wall, separating the life of the city from the water around it?” Winning the 2015 AIA Institute Honor Awards for Regional & Urban Design, the 1,000,000-square-metre BIG U is a protective system that stretches over low-lying geography from West 54th Street south to The Battery and up to East 40th Street, comprising multiple but linked design projects based on different scales of time, size and investment, where each local neighbourhood customises its own set of programmes, functions and opportunities. More than just a flood barrier, it also provides community-desired amenities. BIG analysed the social, cultural, historical and environmental landscape of each community to determine the best site-specific strategies for protection. At East River Park, it raised the topography of the underused areas between the sports fields and along service roads to screen the park from highway noise and protect the neighbourhood from floods. The introduction of bike lanes and conversion of caged bridges into High Line-like green passages allow for pedestrian access into the newly elevated, resilient coastal parkland, while other modes of circulation such as the highway or future subways could be integrated as well. Ingels says, “Many of the world’s cities are threatened by flooding. Most coastal cities today are using typical flood protection measures that create a wall between the city and the water. We’re looking at how existing infrastructure in coastal cities can serve new and better uses—take the High Line for example, a piece of decommissioned railroad that has become one of the most popular promenades in the city. We thought, ‘What if we could learn from the High Line, and create the Dry Line?’ Instead of waiting for infrastructure to become obsolete before converting it into a public amenity, what if we could design the resilient infrastructure of Manhattan to come with positive social and environmental side effects from day one?”

The USD760-million East Side Coastal Resiliency Project was born from the BIG U concept. Jointly funded by the City of New York and the federal government, it runs from East 25th Street to Montgomery Street. Led by the NYC Department of Design and Construction, Department of Parks and Recreation as well as the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency and working with community partners and residents, it will provide improved coastal protection to more than 110,000 vulnerable New Yorkers through 2.2 miles of enhanced waterfront, ecology and urban spaces, demonstrating a new model for integrating coastal protection into

neighbourhoods upon its expected completion in 2024.

BANGLADESH

Mohammed Rezwan, Bangladeshi architect and founder of the non-profit organisation Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha, is well aware that local livelihoods depend on strategies for living alongside and benefitting from waterways.

“I thought as an architect, I would design exciting things to help the poor in my own communities,” Rezwan says. “I considered dedicating my life to building schools and hospitals in flood-prone areas, then realised they would be underwater soon. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that by 2050, the country could lose 16 per cent of its land to floods, and as many as 20 million people could be left with nowhere to live. Ten per cent of people worldwide live less than 10 metres above sea level and in high-risk zones for floods—about 75 per cent of them in Asia. Not only do floods cause the loss of lives and livelihoods, they also severely interrupt children’s education. That’s why I started designing spaces on boats for school. I thought that if children cannot come to school, then the school should come to them.” The floating school collects students from their homes, moors to the riverside and provides on-board small-group instruction. After school, students take home a recharged, low-cost solar lantern, which provides light at night by which they can study and women can do craftwork to earn extra income, which is also sold to community members to fund the initiative. In the evening, the boats project educational programmes onto screens that people can watch from their homes. The project has even helped to develop floating crop beds to ensure year-round food supply and income for families in flood-prone areas.

Working with local boat builders, Rezwan designed the schools by altering traditional Bangladeshi wooden boats, using native materials and building methods. With a main cabin that can fit 30 children, the boats are 55 feet long by 11 feet wide, incorporating a flat-bottomed hull; flexible wooden floors; top-hinged side windows for daylight and natural ventilation; arched metal beams for column-free spaces; outward-inclining bamboo and wood walls; and monsoon-proof curved roofs with large overhangs equipped with solar panels. It costs BDT1,350,000 to build a single-storey school boat, exclusive of equipment, school supplies and other operational costs. Rezwan began with USD500 in 1998, then received a USD5,000 grant from the Global Fund for Children in 2003, followed by USD100,000 from the Levi Strauss Foundation, and a USD1 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2005. Today, Shidhulai’s floating school model has spread across the world, and school boats serve children in flood-prone regions in Cambodia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Pakistan, India, Nigeria and Zambia.

LIFEARK

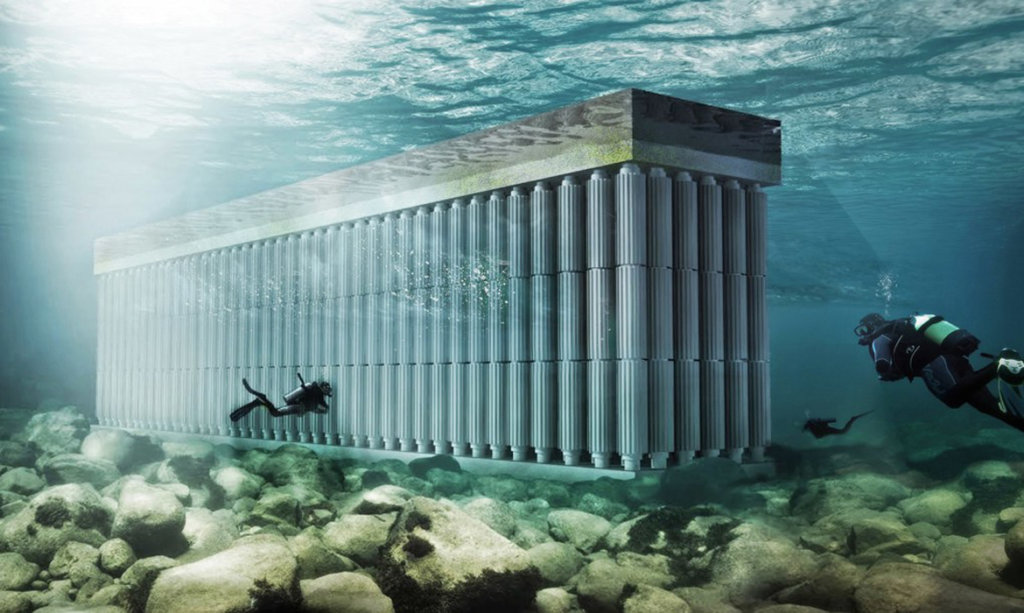

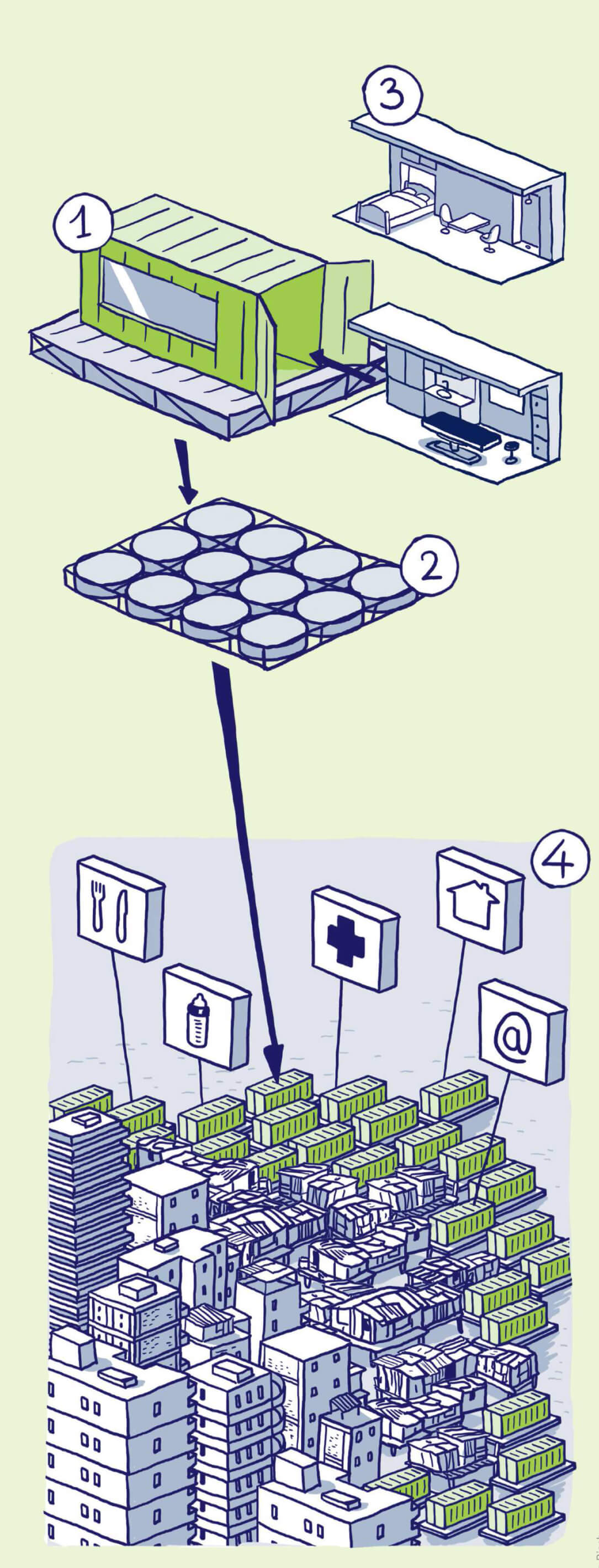

LifeArk is a prefabricated, modular building system for mass-produced, affordable, safe, sustainable and easily deployable and assembled housing. Designed for disaster relief and refugee or homeless housing, these self-sustaining, lifesaving homes for water or land that will mobilise economic development and regeneration for millions of slum dwellers and displaced peoples worldwide can be scaled up into communities in different configurations: a school, hospital, livestock or hydroponics farm, or community centre for small businesses. With the option to operate 100 per cent off-grid, allowing units to be moved around as

needed, LifeArk’s modular roof can be fitted with photovoltaic panels, a rainwater harvesting system where a single-family home can store over 30,000 litres of filtered drinking water, a filtration system so that water needed for all other uses can be pumped up from the river, and a portable sewage treatment system. It was selected as one of 17 semi-finalists in the 2017 Buckminster Fuller Challenge, an annual honour known as “socially-responsible design’s highest award”.

Korean-born American architect Charles Wee, founder of GDS Architects and LifeArk, discusses the need for affordable floating architecture, “There are many floating structures being built around the world to address rising water levels. However, many of them are still extremely expensive and are essentially conventional homes being built on buoyant foundations, and mainly serve a high-priced waterfront housing market. Several factors inhibit existing solutions to truly scale as a solution for communities most affected by climate change: speed, cost and policies. Often, existing floating structures require a significant amount of site preparation, much like that of a conventional home—the speed of delivery and assembly cannot adequately address the rapidly growing need.

Additionally, current projects are simply unaffordable for those who need it most. With the number of climate refugees expected to increase mostly due to flooding, there is a pressing need to proactively respond to this challenge. Many major cities in the developing world are already struggling to properly house their rapidly growing population—a trend that is only expected to grow. For example, in Nigeria, the scarcity of land and affordable housing has pushed people out onto the waters, resulting in the Makoko floating slum community (home to nearly 250,000 residents). LifeArk can rapidly provide resilient homes by master planning communities onto the water, addressing the land scarcity [issue] many cities are facing.”

Roto-moulded with environmentally-stable, recyclable and zero-maintenance high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and injected with polyurethane foam with inherent additives to form a composite material to provide fire resistance, buoyancy, thermal performance and structural values, LifeArk units are prefabricated via a module-based construction system that ensures efficiency in manufacture, assembly, relocation and reassembly, with a lifespan of 20 to 30 years. Interior walls, flooring and finishes may be customised. Arriving on-site, each module can be quickly assembled by unskilled workers using standard tools in just two hours. The only skilled labour required on-site is connections to sewers. LifeArk cuts the total design and construction time for prefabricated architecture in half, while its persquare- foot cost is expected to be approximately one-third of the price of conventional ground-up housing. LifeArk will apply a manufacturing protocol using US life safety standards to all parts of the world to use locally sourced HDPE and set up factories for manufacture, final assembly and site adaptation as required in future.

Olthuis concludes, “We are in a very exciting moment in time where architects and urban planners have to rethink the way we live and use our resources. We have to look carefully at how space is being used, and that space can change functionality immediately if it’s on water. You can pop in or take out floating functions for different uses throughout the year: parks, offices, houses, entertainment and car parks. If you go one step further, cities that are close to each other, like 50 or 100 kilometres from each other, both next to water, could start to build and share big public functions. A city is in constant evolution: from a normal city to a green city, a smart city and eventually a blue city, and that blue city should be better than all the cities before it.

Water is the next frontier; it’s the next place where cities will start to expand, while improving liveability, sustainability, safety and flexibility.”

Click here for the full article

Click here for the website