Watervilla IJburg

Urgent Architecture, Bridget Meinhold, 2012

A floating home in Amsterdam takes advantage of the water-based site, easily adapting to fluctuations in water levels

Urgent Architecture, Bridget Meinhold, 2012

A floating home in Amsterdam takes advantage of the water-based site, easily adapting to fluctuations in water levels

G8, Dec 2011

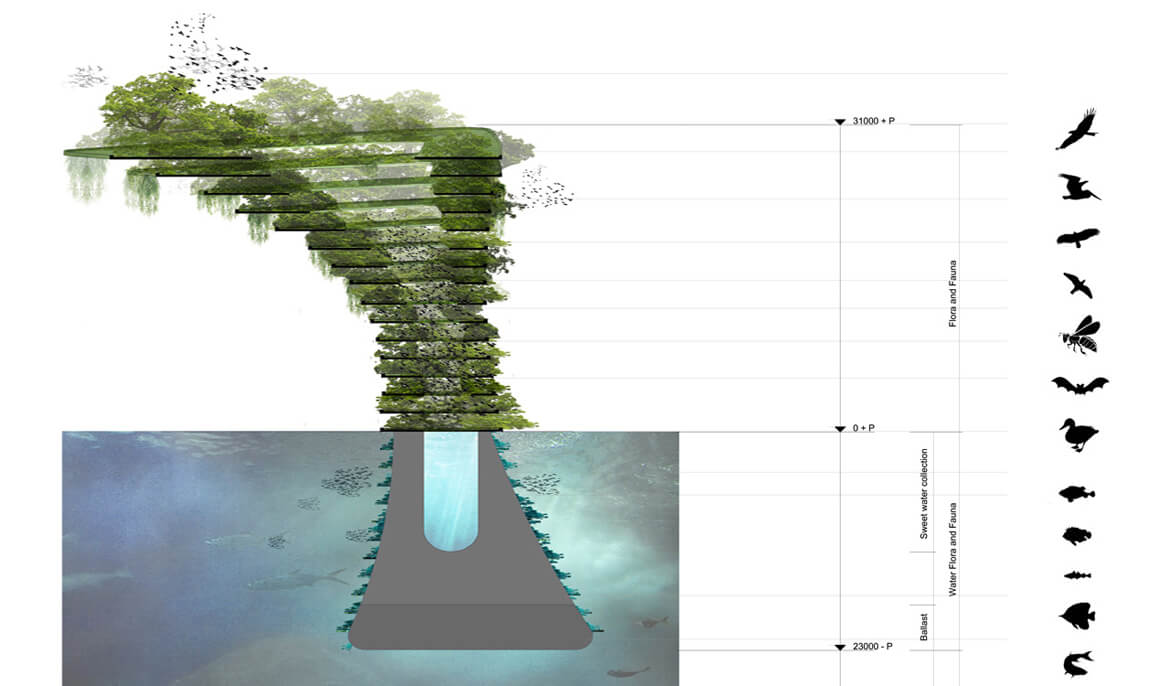

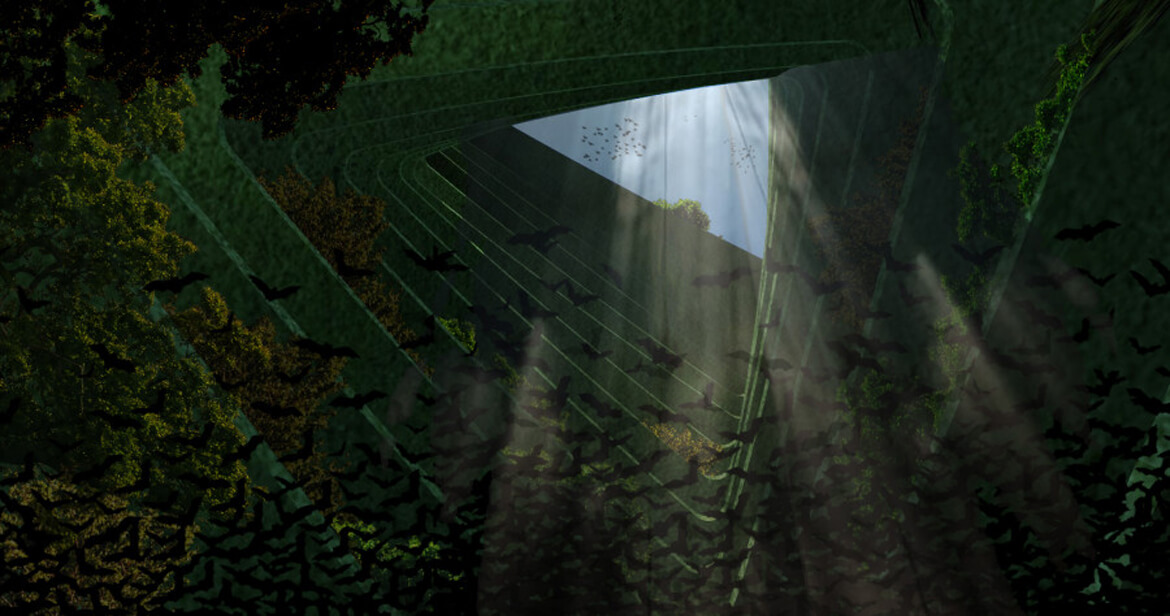

The Sea Tree, striking a keen resemblance to the hanging forest in an Avitar film, are floating habitats that create a safe haven for flora and fauna both underwater and above it. As urbanization and climate change advance, the respective habitats for animals and plants are at a great risk, especially in urban centers. To counteract some of those factors, Waterstudio.nl came up with these protected reserves to help bring positive environmental benefits to the city.

The Sea Tree is a floating structure moored out in the water by a cable that holds a series of layers for a variety of species. The structure would be built using offshore technology similar to oil storage towers, which can be found on open seas and can be designed for specialized locations like rivers, lakes or the ocean. Totally self-sufficient, the structure serves as a base that will eventually grow and support a wide range of flora and fauna including birds, bees, bats and other small animals that will help bring a positive environmental benefit to the city. The structure is also designed with narrow and steep sides at the water line so that people cannot trespass and bother the animals.

Waterstudio.nl developed this concept to help protect natural habitats in urban areas and they thought it would be especially perfect for New York City. Their hope is that large companies, like oil companies, would purchase these structures and donate them to cities as a way of showing their concern for animal habitats. Moored to the bottom of the water floor, the structure can move slightly with the wind and waves. Eventually the animals would overtake these forms and make them their own without taking up valuable space on land.

The Financial, Madona Gasanova, Dec 2012

On 19 December, widely renowned Dutch architectural companies will be presenting the latest trends and tendencies in the contemporary Dutch architectural sector. The exhibition aims to present leading Dutch architectural firms with innovative designs to a Georgian audience and architectural market. Modern technologies, sustainable, intelligent buildings – which respond to nature, the environment, social needs, are innovative in their design and materials, are incorporated in the projects of these Dutch architects.

“According to the global picture, more than half the population is living in cities, cities becoming “places for urban exchanges”. All over the world, it turns out; there is enormous demand for convincing examples of architecture that provide solutions. In many cases these solutions take the form of social projects, intended to bring about immediate improvement in living conditions,” Dr. Lena Kiladze, Curator of Exhibition Days of Dutch, told The FINANCIAL.

“In this case it’s becoming very important to have dialogue, discuss problems and define new language in contemporary architecture,” Kiladze said.

“Today Dutch design and architecture has established a world reputation. Dutch architects and construction have also established a strong international reputation for their innovative, ground-breaking, problem-solving approach. Over the centuries, Holland’s architects and builders have been tried and tested by the country’s struggle against the sea and the challenge of accommodating the population in a small country. Today Dutch architecture is reinventing itself and proving that architecture works – not just in direct function, but also in its programmatic reach, in its cultural effect, and ultimately in its value to society,” said Kiladze.

“Today Dutch design and architecture has established a world reputation. Dutch architects and construction have also established a strong international reputation for their innovative, ground-breaking, problem-solving approach. Over the centuries, Holland’s architects and builders have been tried and tested by the country’s struggle against the sea and the challenge of accommodating the population in a small country. Today Dutch architecture is reinventing itself and proving that architecture works – not just in direct function, but also in its programmatic reach, in its cultural effect, and ultimately in its value to society,” said Kiladze.

The following Dutch architectural companies will be participating in the event: Allard Architecture; Casanova + Hermandez Architects; Cie; Concern; Hans Moor Architects; Mecanoo Architects; MVRD; Neutelings; NIO Architects; UArchitects; UNStudio; Waterstudio; Rene van Zuuk Architecture.

Kiladze said that with the collapse of the Soviet Union architectural problems in all former republics became more visible. “Georgian architecture started changing from state-controlled and state-approved architecture, globalization, critical regionalism, post-modern culture and integration with the West, forced a restructuring of Soviet architecture and soviet urban planning.”

She added that there are lots of questions on many problems, for example whether Georgia should move toward globalization or toward critical regionalism and how we can define contemporary Georgian architecture. “In today’s globalized world it is very hard to define the meaning of architecture,” Kiladze said.

“Architecture has always been a reflection of the collective consciousness, a physical encapsulation of evolving lifestyles. Our new perceptions of life arise from this changing society and develop according to which region, culture or city they are from. Our architecture reflects our life and our problems,” Kiladze told The FINANCIAL.

Home review, Mala Bajaj, Dec 2012

Waterstudio.NL is an architectural firm located in The Netherlands that is confronting the challenge of developing solutions to the problems posed by urbanisation and climate change head on.

The general prognosis is that by 2050 approximately 70% of the world’s population will be living in urbanised areas. Given the fact that about 90% of the world’s largest cities are situated on the waterfront, Waterstudio.NL has arrived at a solution; it is asking people at large to rethink the way we live with water in the built environment.

Considering the unpredictability of future developments and unanticipated needs, Koen Olthuis, the principle of the firm, believes that we should come up with flexible strategies – equipped to combat the imminent progression towards urban areas. Koen’s vision is that large-scale floating projects in a metropolitan environment can successfully provide a tangible solution to future problems, one that is both flexible as well as sustainable.

The Dutch are long known to link technology and progress, in fact, The Netherlands is a country that would not be inhabitable without its sophisticated flood defenses and a superior water management structure.

We at Home Review are delighted to introduce you to a truly inspirational, driven, creative professional who through his compassion for the Earth’s environment is busy acquainting the world with his very learned and intrinsic solutions.

How would you classify the architecture you practise?

According to me, today’s designers are an essential part of the climate change generation and I strive to enhance their perspective by considering urban components that are dynamic instead of static.

My firm’s solutions called City Apps, are floating urban components that add a particular function to the existing static grid of a city. Using existing urban water as building ground relieves space for a new density, providing worldwide opportunities for cities to respond flexibly to climate change and urbanisation.

How did you your unique style of architecture develop?

As a young architect, I became fascinated by the structure of the Dutch landscape with its water and land connection. At that time, living on water was still limited to the well-known traditional houseboats. After two years of combined land and water projects, I started up Waterstudio.NL with Rolf Peters at the end of 2002. Ours was the first architecture firm in the world exclusively dedicated to living on water. The company was a pioneer in a new market. To bring the market to maturity, the main focus was to change the perception of the general public. Waterstudio began with an ambitious plan to develop innovative concepts in both technological and urban design fields. The firm conviction that living on water is essentially no different from living on land, just with a different foundation technique, spurred the bureau on to develop types of housing with a greater density and higher quality than the usual houseboats in a recreational countryside setting.

Where did you first apply your novel vision?

The first city, in which this vision is being developed, is The Westland, located near The Hague in Holland. This project incorporates both floating social housing, floating islands, and floating apartment buildings.

In 2010, the government of the Maldives too agreed to develop a floating city, floating islands, floating golf courses, floating hotels, and a floating conference center as a part of a joint venture. This masterplan for the Maldives is a solution in response to the urgency caused by rising sea levels, but these new developments will also be beneficial in encouraging social and economic advancement. All over the world people have started to see the potential of floating developments. This has resulted in projects in several countries like China, UAE, and European countries.

Can your ideas be applied in third world countries, where architecture is often seen as providing lesser solutions and creating more problems?

Floating developments, in particular, have the ability to make a positive impact on slum communities that are living in conjunction with water. There are many communities all over the world that are threatened by rising sea levels, and Waterstudio seeks to ease the lives of people that are currently living without the most fundamental of necessities.

Slum communities are here to stay, and aiding these communities by upgrading living standards will fortify the cultures associated with these areas, unmatched by any other communities in the world. Our project City Apps offers a flexible and adaptable design, creating solutions to specific needs of each area.

What steps have you taken to spread your vision and allow the world to benefit from your unique architectural solutions?

In the first few years, it became clear to me that the market was lagging behind my vision. So Waterstudio started to target the media. Not just in the Netherlands, but worldwide.

In a time when new media was rapidly emerging via Internet, and climate change and water issues were receiving a lot of attention because of the flooding in New Orleans, the tsunami in Asia and Al Gore’s film ‘An Inconvenient Truth’, Waterstudio’s vision was soon noticed. News teams from Discovery Channel, the New York Times and Newsweek paid attention to the story. My vision grew rapidly: from water houses to larger complexes, culminating in floating cities and dynamic urban components.

Neeraj Bhatia, Mary Casper, Dec 2012

The petropolis of tomorrow, Neeraj Bhatia & Mary Casper, 2013

In recent years, Brazil has discovered vast quantities of petroleum deep within its territorial waters, inciting the construction of a series of cities along its coast and in the ocean. We could term these developments as Petropolises, or cities formed from resource extraction. The Petropolis of Tomorrow is a design and research project, originally undertaken at Rice University that examines the relationship between resource extraction and urban development in order to extract new templates for sustainable urbanism. Organized into three sections: Archipelago Urbanism, Harvesting Urbanism, and Logistical Urbanism, which consist of theoretical, technical, and photo articles as well as design proposals, The Petropolis of Tomorrow elucidates not only a vision for water-based urbanism of the floating frontier city, it also speculates on new methodologies for integrating infrastructure, landscape, urbanism and architecture within the larger spheres of economics, politics, and culture that implicate these disciplines.

Articles by: Neeraj Bhatia, Luis Callejas, Mary Casper, Felipe Correa, Brian Davis, Farès el-Dahdah, Rania Ghosn, Carola Hein, Bárbara Loureiro, Clare Lyster, Geoff Manaugh, Alida C. Metcalf, Juliana Moura, Koen Olthuis, Albert Pope, Maya Przybylski, Rafico Ruiz, Mason White, Sarah Whiting

Photo Essays by: Garth Lenz, Peter Mettler + Eamon Mac Mahon, Alex Webb

Research/ Design Team: Alex Gregor, Joshua Herzstein, Libo Li, Joanna Luo, Bomin Park, Weijia Song, Peter Stone, Laura Williams, Alex Yuen

Co-published with Architecture at Rice, Vol. 47

Architectenweb.nl, Nov 2012

Met zijn inzending App-grading Wet Slums heeft Waterstudio de Architecture & Sea Level Rise Award 2012 gewonnen. Het bureau stelt drijvende bouwwerken voor om in te spelen op specifieke behoeften van verschillende sloppenwijken.

Momenteel woont naar schatting een miljard mensen in sloppenwijken en wereldwijd dijen deze gemeenschappen uit. Voor sloppenwijken die gesitueerd zijn langs en op het water – de zogenoemde wet slums – kunnen drijvende toevoegingen een positieve bijdrage zijn.

Aanpasbare oplossingen

In wet slums, die net als de meeste sloppenwijken kampen met een hoge dichtheid, kan de ruimte worden gevonden op het water. De drijvende uitbreidingen of City Apps, zoals architectenbureau Waterstudio ze noemt, kunnen worden toegevoegd waar dat nodig is.

City Apps kunnen voorts verschillende functies vervullen. Waterstudio heeft een aantal City Apps ontwikkeld om wet slums te voorzien van voedsel, energie, onderdak en waterzuivering. De applicatie of applicaties waaraan in een specifieke sloppenwijk grote behoefte is, kan of kunnen worden toegepast.

Inhabitat, Bridgette Meinhold, Nov 2012

Waterstudio.nl, the leader in floating architecture, is now working on helping slums cope with climate change and rising sea levels with a collection of floating functions called City Apps. Slums are tight on space and many have grown up along the water and are at risk for rising sea levels. Waterstudio.nl’s City Apps can provide critical infrastructure as needed. Whether the area needs additional safe housing, sewage treatment, more electricity or space to grow food, these modular and flexible units can serve as catalysts for change. The Netherlands-based studio was recently awarded the prestigious “Architecture & Sea Level Rise” Award 2012 from the Jacques Rougerie Foundation with their entry: App-grading Wet Slums.

Wet slums are slum communities that live in conjunction with the water and many occur around the world. The connection to the water also puts them at risk for climate change and rising sea levels. To aid these communities, Waterstudio.nl has been researching how they can put their know-how of floating architecture to good use. They’ve come up with a series of flexible, adaptable City Applications or City Apps that can aid these communities now and in the event of disaster. With little space available inside the slum, the nearby water provides open space in which to add critical infrastructure to the community.

The City Apps consist of four different types of floating infrastructure designs that can provide food, water, shelter and energy. A floating field can be used as a large community garden to grow food for consumption in the slum or produce food that can be sold in the city. Floating sewage stations can provide potable water for drinking and help process waste to improve hygiene. Floating buildings can be used for additional housing or used as schools, clinics or community centers. Finally floating photovoltaic systems generate energy for the community.

In conjunction with the design of the City Apps, Waterstudio.nl has been researching about 20 Wet Slums around the world and determining their characteristics. This fingerprinting of the slums will help leaders understand the needs of each community and more aptly be able to provide aid and support especially in the event of a disaster. Waterstudio.nl hopes to partner with more organizations to spread their research and help these communities. Their work was recently awarded the “Architecture & Sea Level Rise” Award 2012 from the Jacques Rougerie Foundation.

Le figaro magazine, Nov 2012

Des Villes Flottantes

L’architecte Koen Olthuis est surnommé “le Hollandais flottant”. Sa dernière idée, Thalassophilanthropy, repense la construction des villes qu’il considerère comme obsolete. Dans sa ville, les fondations flottantes permettent à lafois de déplacer les maisons et d’éviter les inondations. Comme si l’île de Manhattan avait pu se serélever ou fuir l’ouragan Sandy. Prix Architecture et problématique de la montée des eaux.

Architizer, Lamar Anderson, Oct 2012

Vincent Callebaut’s Coral Reef Island, a proposal for Haiti. Photo courtesy of Vincent Callebaut

What is it about water that captures our imaginations? Yes, we certainly have been warned about rising sea levels and the 100-year flood’s awkward rechristening as the 3-to-20-year flood. But if stats really got through to us, obesity wouldn’t be a crisis and we would all have retirement savings. When it comes to visionary designs for the future of the built environment, flood scenarios dominate the design briefs—standard-issue earthquakes, tornadoes, and volcanoes just can’t catch a break.

In our collective architectural imagination, the next century looks like a fanciful sci-fi resort in which we jet from floating airports to floating Scottish villages, soak in pools that float (wink-wink) in rivers, and furnish our floating apartment complexes with flat packs we bought in floating IKEAs.

And now that Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy has filled New York’s subway tunnels with water, it doesn’t seem so farfetched to imagine a fleet of gondolas sending commuters down a river underneath Broadway (which would certainly be an interesting entry in our Architecture + Weather category in the A+ Awards!). So, in preparation for only the most picturesque of disaster scenarios, we bring you some of our favorite futuristic designs for the all-waterfront property of tomorrow.

The Belgian architect and vertical-farming enthusiast Vincent Callebaut thinks planners in Haiti should take a cue from the organic architecture of coral reefs. His proposal calls for a modular reef built atop seismic piles on an artificial pier in the Caribbean. In Callebaut’s scheme, two wavy hills of wood-clad metal modules bookend a central valley built out with terraces and cascading food-producing gardens. The modules form passive houses that could shelter more than one thousand Haitian families come the next catastrophe.

As a lowland continually beset by flooding, the Netherlands already has its share of floating houses and villas. “The toolbox of floating developments in Holland is still not so large… concepts with high density are not available.” WaterStudio says in its design brief. So the firm is working on the Citadel, which will be Europe’s first floating apartment complex. Part of a 1,200-house urban development called New Water in the city of Westland, the project will push beyond the country’s usual relationship with its excess water—constant pumping—and intentionally flood the site. The apartments will be built from 180 modules surrounding a courtyard that will be anchored on a concrete caisson foundation. Like the luxury watercraft it actually kind of is, the 60-unit Citadel will rise and fall with the water, offering its residents wetland views and berths for small boats.

After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Tangram 3DS and E. Kevin Schopferwanted to boost the country’s resilience with an adjacent floating city in the Caribbean. The designers imagine this Harvest City as a solar- and wind-powered mini-metropolis for 30,000, complete with its own agriculture and light industry. Their plan calls for four zones of concrete-hull modules that span a diameter of two miles, linked by a linear system of canals. Residents would live in four-story tilt-wall concrete structures, run light-industry operations in Quonset hut warehouses, socialize in the harbor city center, and farm crop circles—dubbed “floating pie pans”—filled with topsoil.

This hotel/greenhouse/waterborne Slinky by the Russian firm Remistudiocan withstand tidal waves and grow vegetables.

Designed to ride out another Katrina, the New Orleans Arcology Habitat(NOAH) combines flood-ready buoyancy with an open triangular structure that sends severe winds straight through the center of the building. Proposed by E. Kevin Schopfer, the massive mixed-use complex would provide housing for 40,000 and include three hotels and casinos, cultural facilities, a district school system, and a health-care facility on the Mississippi River. Also: organic gardens.

For those of you who prefer tiny houses to floating high-rises, a Japanese company called Barier has the solution for you. Barier’s 32-sided, 540-square-foot watertight houses can survive earthquakes, will stay upright in a tsunami, and come with a reassuring slogan: “Soccer ball-shaped houses strong with disasters.”

No discussion of next-next-gen splashy, speculative urban aquatic design would be complete without Vincent Callebaut’s floating lilypad city for the year 2100, when 50,000 of Callebaut’s climate refugees will flee land to found their own eco-city. As you would expect from any decent post-apocalyptic Eden, this one thrives on aquaculture, organic farming, and amphibian metaphors.