Liquid Assets, TIME

TIME, Carla Power, Sept 2011

The Amsterdam street that Monique Spierenburg lives on is a portrait of 21st century prosperity. Potted olive trees line balconies, and windows afford glimpses of minimalist kitchens and airy rooms decked with art. Spierenburg shows a visitor around her three-story house, pausing to point out her husband’s woodworking shop and their sauna. Recently she had the painters in, but midjob they downed tools and ran out in fright. “The house was moving,” she shrugs.

Or rather, bobbing. Like neighboring dwellings, Spierenburg’s house floats. Amsterdam has a history of watery habitations, of course, its houseboats having long attracted free-spirited types. But the floating houses in the neighborhood of IJburg are aquatic life 2.0: they’re not boats, but buildings with plots of water instead of earth. Kids wear life vests when they play on the jetties that serve as streets. Gardens grow on pontoons moored next to the houses, which rise and fall with water levels but are anchored to piles so that they don’t float away — unless the owners want to, in which case tugboats can move them elsewhere. “Normally you think of a house being stable,” Spierenburg laughs. “It changed our vision of what a house is.”

Altering preconceptions on a broader scale is now the aim of a whole cadre of Dutch water architects and engineers. Floating buildings, they argue, could help tackle three of the gravest problems facing the planet: rising seas, growing urbanization and ever greater numbers of people. With the planet’s population set to hit 9 billion by 2050, the world is going to need more housing, mostly in urban areas. Cities have always been built near water: about 90 of the world’s 100 biggest cities are built on coasts or rivers. But they’re going to have to learn to live with lots more water in the coming century, when seas are forecast to rise up to 60 cm. With 200,000 people moving from rural to urban spaces every day, they will also be more crowded, which means flooding will wreak even more havoc than it does now. According to Koen Olthuis, one of the architects involved in IJburg and founder of architecture firm Waterstudio: “For the climate-change generation of architects, the key task will be learning to work with water, rather than against it.”

Over the centuries, the Dutch have mastered doing both. Nearly half of the country is below sea level, so it survives thanks to elaborate improvisations, from a system of dikes to building on man-made forests of wooden underwater piles. The past decade has brought a new approach: building floating structures on platforms of polystyrene and concrete. The country now has hundreds of floating structures, ranging from four-bedroom houses to small-scale office buildings to a floating prison, currently docked near Amsterdam. The projects are getting bigger: next year, Waterstudio begins work on a floating apartment complex called the Citadel — complete with underwater parking — as part of a waterscape development in South Holland. “Floating structures are already part of our urban planning,” says Hans Ovink, director of national spatial planning at the Netherlands’ Ministry for Infrastructure and the Environment.

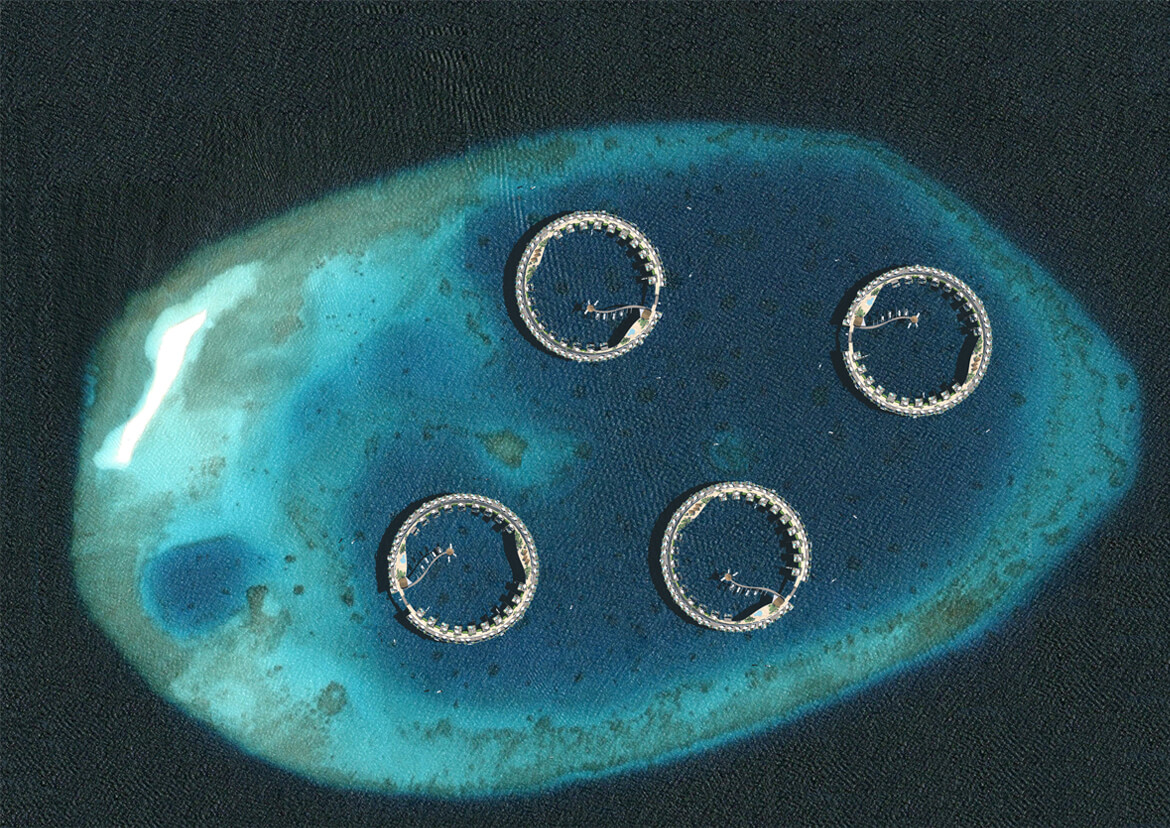

The Dutch aren’t the only people building on water — Dubai has famously fashioned islands shaped like a palm tree and a map of the world from sand dredged out of the Persian Gulf — but nobody is doing it quite as extravagantly as the Dutch. Dutch Docklands, a water-development company founded by Olthuis and hotel developer Paul van de Camp, has partnered with the Maldives, a country of 1,190-odd islets, to build a floating golf course, a convention center and 43 private islands in the Indian Ocean. When van de Camp proposed the developments to the Maldives President, “it was like in the ’60s, when you said, ‘We’ll go to the moon.’ ” Work on the $500 million golf course begins in January 2012, with the entire project due for completion in 2015. After that, there are plans for an even more ambitious phase of island development: a floating city, with 20,000 affordable homes for Maldivians.

How green are these visions? Very, insist their champions. The port of Rotterdam boasts a floating exhibition center designed by the Delft-based water-management firm DeltaSync. Made of three geodesic domes, it uses solar power and local water and energy sources, thus using 60% less energy than comparable structures. The mobility of floating structures is another green benefit, argues Olthuis. On land, unwanted buildings are left derelict or torn down. Floating ones can be recycled by being towed to new locations for a fresh purpose. The ocean’s breezes and water can also be harnessed for heating and cooling. Docked near a building yard outside the Dutch town of Hoorn is a three-story model home built by the De Peyler construction company, which has sold about 20 of them at around $470,000 each. The water the house sits on helps cool and heat it. Flexible pipes anchored to the land provide drinking water and electricity; another pipe removes waste. “The technology is here,” insists De Peyler’s Nick Capel, striding around the third floor’s master bedroom. “You are standing on it.”

Skeptics see the floating projects as novelties rather than serious solutions to urban congestion. The Maldives development is “an interesting experiment,” says Erik Swyngedouw, professor of geography at Manchester University. “But it’s one thing to build floating houses. It’s another thing to do it on a large scale, to get energy and food in, and to get all the garbage out.” And while building floating structures in sheltered inlets or at former ports is accepted practice, building further out to sea remains another issue altogether. “At the moment, it’s not possible to make very large or very high structures without taking into account the effect of the waves,” says Han Meyer, chairman of urban design at Delft University of Technology’s Faculty of Architecture. “When the weather is calm, it’s nice to live in a floating home, but you really have to think about what happens when there are extreme weather events.”

Olthuis’ solution is to think big. “A large structure reacts less to normal waves than a small one,” he says. Although it will be partly protected because it’s in a lagoon, the Maldives golf course he has designed will be supported on rigid floating structures surrounded by semirigid ones to absorb any energy from the waves. “The golfers will not feel the difference from a land-based course,” Olthuis claims. So confident are he and van de Camp of the success of their Maldives project, they have begun scouting water rights in cities around the world, from New York City and London to Rio de Janeiro and Hong Kong, purchasing tracts of water near developed areas (nondisclosure agreements prevent them from saying more). “He who controls the water, controls the development on it,” says van de Camp. His bet: that floating technology will turn rising seas into prime real estate.