By Stas Margaronis

RBTUS

April.29.2019

Source: Waterstudio

Sea level rise is magnifying the flood damage from hurricanes and storms posing a growing threat to coastal communities around the world. In response, a growing number of flood and storm specialists as well as architects, home builders and developers are arguing that coastal cities need to be rebuilt for sea level defense.

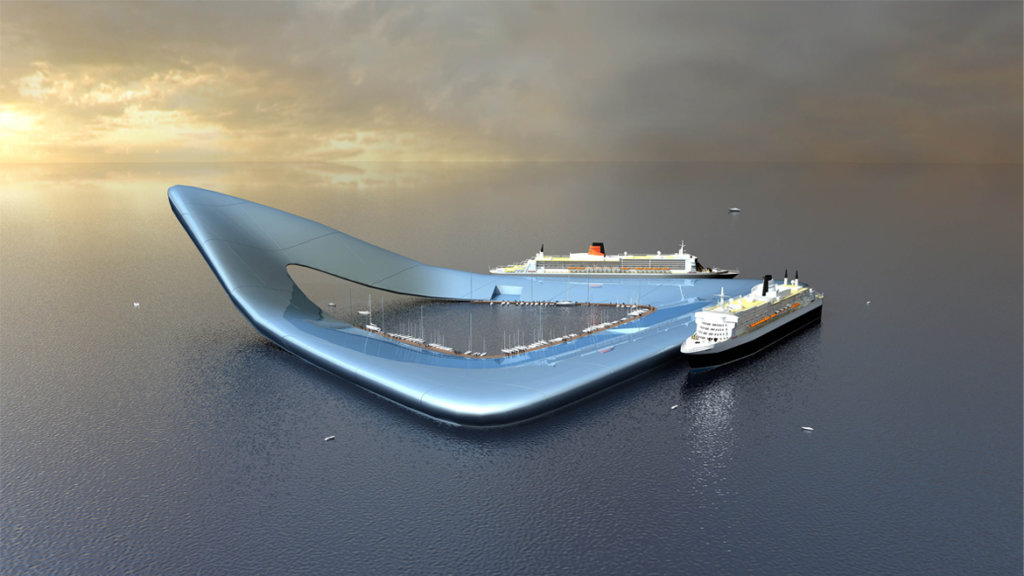

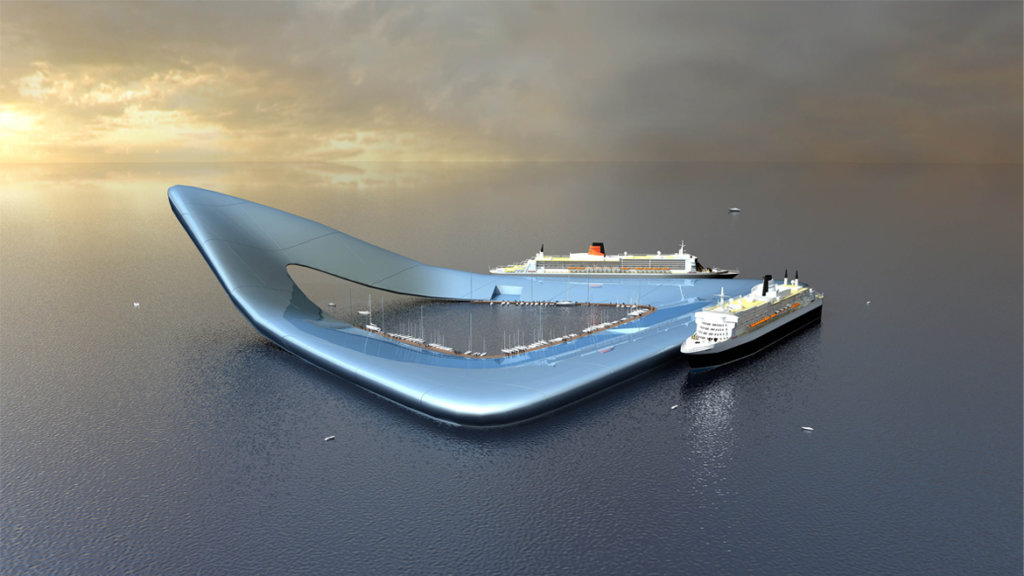

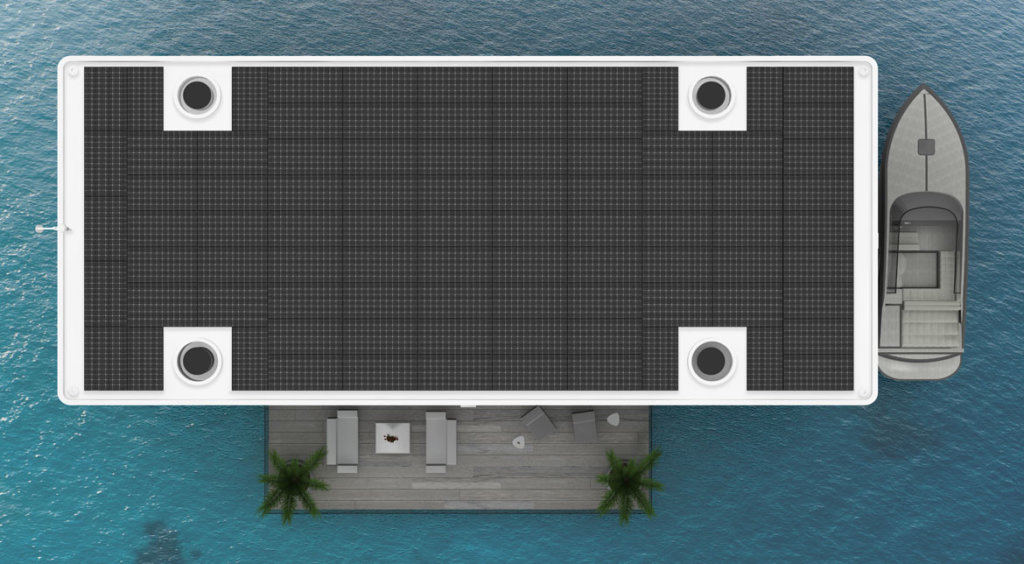

The movement toward floating structures is growing and looking at how investing in sea level defense can also create new real estate development. The key is to inspire coastal cities and communities to build new houses, garages, farms and even cruise ship terminals (see rendering above) on the water.

Koen Olthuis, a Dutch architect of floating homes and structures who began his architectural firm Waterstudio in 2003, believes that floating structures can provide one component of the climate change adaptation strategy.

He argues that: “Waterstudio.NL is an architectural firm that has taken up the challenge of developing solutions to the problems posed by urbanization and climate change. Prognoses are that by 2050 about 70% of the world’s population will live in urbanized areas. Given the fact that about 90% of the world’s largest cities are situated on the waterfront, we are forced to rethink the way we live with water in the built environment. Given the unpredictability of future developments we need to come up with flexible strategies – planning for change. Our vision is that large-scale floating projects in urban environments provide a solution to these problems that is both flexible as well as sustainable.”

Olthuis says that political and business leaders as well as planners and urban development stakeholders need to start thinking about rebuilding their waterfronts with floating structures in mind: “A next step would be expanding (the) urban fabric beyond the waterfront: building normal urban configurations on water locations, with normal densities and usual typologies such as apartment-buildings, semi-detached housing, etc. Water-based neighborhoods that look and feel just like traditional land-based areas but just happen to have a floating foundation that allows them to cope with water fluctuations.” [1]

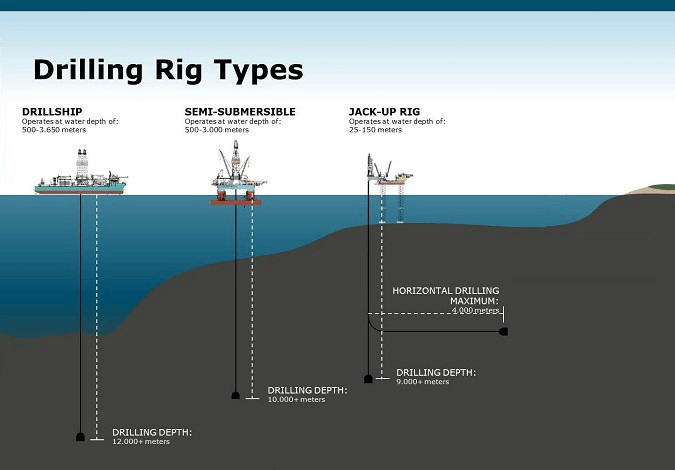

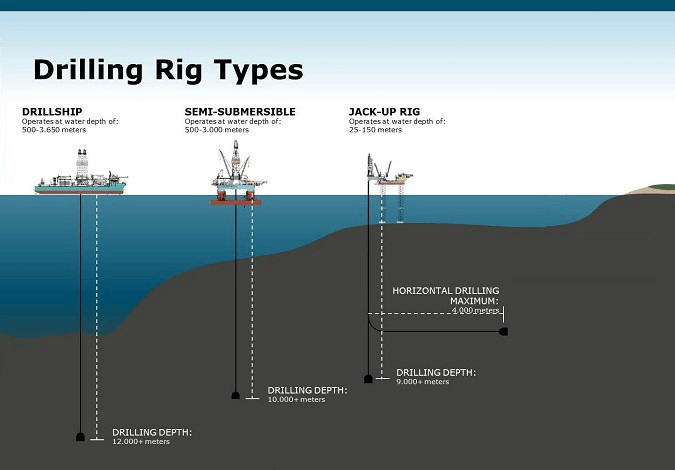

Olthuis, who is descended from a family of shipbuilders, notes that the offshore oil and gas industry provides a role model. Offshore drilling platforms suggest ways to build structures in the age of sea level rise: “There are many important lessons we can learn from the offshore oil and gas industry about building safe and sustainable houses in the water.”

Offshore drilling is more challenging than onshore drilling due to the lack of stability (particularly for floaters), the corrosive water environment, space constraints and the need for more complex logistics and support. Offshore drilling rigs are broadly divided into bottom-supported rigs and floaters.

Olthuis has been inspired by the jack-up rig which he uses in the design of a house. The jack-up rig allows for offshore deployment in shallow water:

“Jack-up rigs are floated out to the drilling location, and they have retractable legs that are lowered down to the seafloor. Jack-up rigs can only work in water depths less than the length of their legs, typically limiting operations to less than 150 meters/500 feet. When drilling is completed, the legs are raised out of the water, and the rig becomes a floating barge that can be towed away (‘wet tow’) or placed on a large transport ship (‘dry tow’).”2

Source: Maersk

Another potential model is the Allseas Pioneering Spirit, a mega ship, which lifts and transports offshore drilling platforms to and from their foundations in the open sea. This shows that the technology already exists to transport large structures like apartment buildings that could be built on land and transported onto pedestals in the water as the photo below suggests: 3

Source: Allseas

FLOATING & JACK-UP HOUSE DESIGN

Olthuis has recently returned from Miami, Florida where he has designed a house that can float on the water or be raised above the water by an internal jack up system.

Olthuis says the hybrid floating and jack up house would provide the stability of a house on land with the versatility of being on water so as to compensate for sea level rises and storm water surges. He is looking at markets in Florida and New York for the new housing developments.

Source: Waterstudio.nl

The Waterstudio design allows the homeowner to “live in comfort and luxury in total autonomy, and enjoy life between the sea, the sky and the city. Dock in a metropolitan marina or anchor in a tranquil bay.”

Source: Waterstudio.nl

In the manner of a semi submersible oil rig with a propulsion system, the Waterstudio floating house is also self-propelled:

Source: Waterstudio.nl

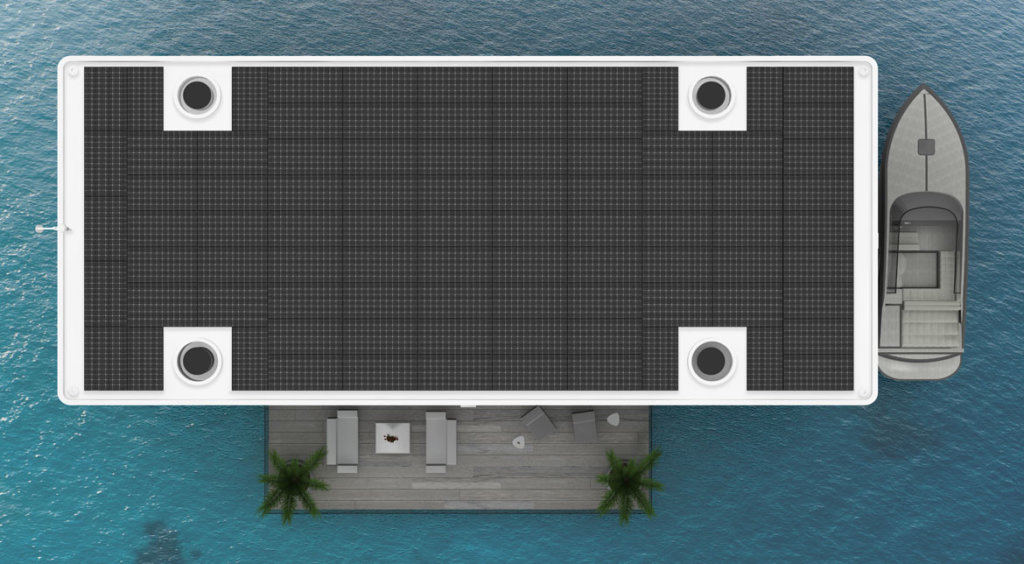

The design also contains a solar roof and batteries to make it largely energy self-sufficient:

Source: Waterstudio.nl

However, Olthuis’ floating home “is not cheap and costs 5.5 million Euros (or about $6.1 million) to build, but it offers some elements that could help establish the foundation for floating houses, apartments and retail outlets being built in the water.”

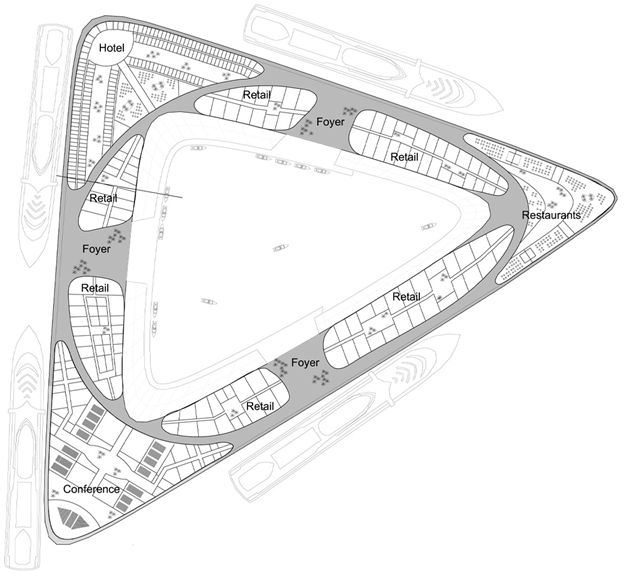

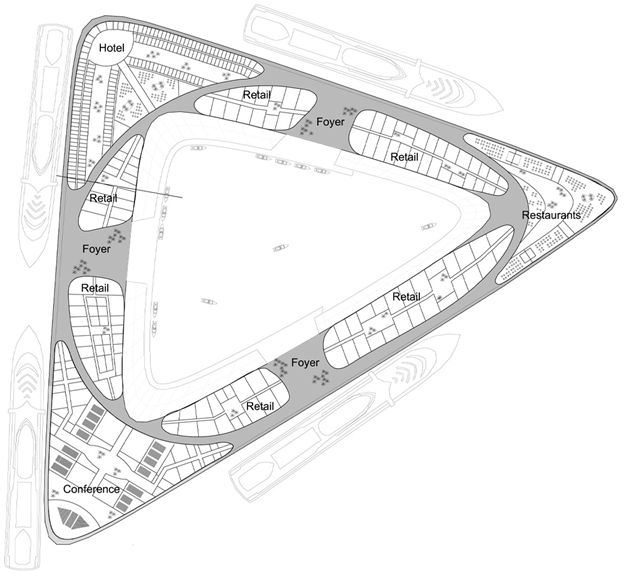

FLOATING CRUISE TERMINAL

As demand for cruise ship travel is on the increase, more ports are looking to build cruise ship terminals to attract tourism.

Waterstudio proposes to build floating passenger ship terminals that can reduce capital costs compared to building terminals on land. This creates the possibility for ports, that lack deep financial pockets, to access state-of-the-art cruise ship terminals at lower costs and with less permit approval delays. Please see the rendering above.

Olthuis says the floating cruise ship terminal concept can also provide temporary housing for an Olympic Games or World Cup soccer event. The cost of putting on special events can be reduced if floating structures are used that can be towed from venue to venue.

His idea is to build the terminal, support it with shopping and other amenities and berth several cruise ships so as to accommodate thousands of floating bedrooms. Below is the floor plan:

Source: Waterstudio NL

FLOATING GARAGES

As downtown areas become increasingly congested, Olthuis makes the case for floating parking garages.

McGregor, the maker of vessel hatch covers, built a floating garage in Sweden that was completed in 1991:

Floating parking structure, Gothenburg, Sweden Completed 1991. Client: Municipality of Gothenburg, Sweden Main particulars: Mooring and access equipment. The floating garage, the P-Ark, can hold more than 400 cars and can be relocated to respond to changing parking requirements. Certified: Lloyd’s Register (LR) Source: McGregor

McGregor argues that as land is limited in both urban areas and ports, the building of parking garages is increasingly constrained. A shallow draft, multi-story, floating parking garage offers an ideal solution to congestion problems.

The company says that “A floating car park requires minimal civil works on the quay side before it can be towed into position and put into use. Compared to building a fixed garage, there is very little disturbance to the surroundings and the unit can be re-located in the future, should the parking situation change… Our floating garages can be designed and painted to blend in with the surroundings, or the large exterior surfaces can feature graphics for advertising, thus generating additional income. All our floating car parks are tailored to suit the customer’s requirements.” [4]

FLOATING HOUSING DEVELOPMENT

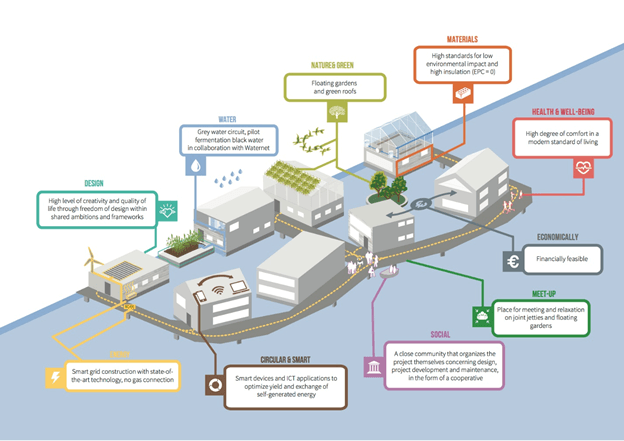

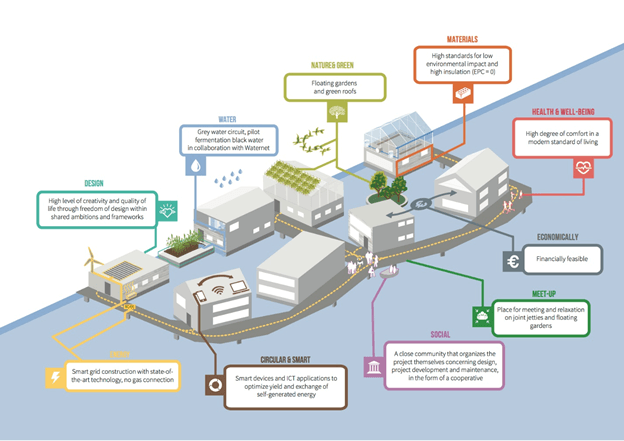

For centuries, the Dutch have built up their cities and towns reclaiming land from the sea. At a time when land is scarce and expensive, they have also begun building houses and other structures on the water. In Amsterdam a new floating housing development generates new housing and new homeowners adding value to the existing community.

The Schoonschip floating community creates new value to an older neighborhood by adding 46 households and a community center on 30 floating platforms. Source: Schoonschip

The Schoonschip housing development is composed of structures floating in the water on concrete foundations that its builders say will be sustainable and alleviate the challenge from higher sea levels:

The water homes are well-insulated … and will not be connected to the natural gas network.

The heat will be generated by water pumps, which extract warmth from the canal water, and passive solar energy will be optimized.

Tap water will be heated by sun boilers in warm water pumps; all showers are equipped with installations that recycle the heat.

We are producing our own electricity with photovoltaic solar panels. Every household has a battery in which temporarily unneeded energy can be stored.

All water homes are connected to a communal smart grid. This smart grid makes it possible to trade energy efficiently amongst the households. 46 households will share only one connection to the national energy grid!

Gray water (i.e. washing machine) and black water (i.e. toilet) will be ‘flushed’ by a separate source of energy. Waternet will eventually include us in their pilot project, which delivers the toilet water to a bio-refinery, in order to ferment it and transform it into energy.

All homes will have a green roof covering at least one third of the roof’s surface.[5]

Sjoerd Dijikstra, a spokesman for the Schoonschip development, explained how the floating housing development works: “The Schoonschip … development in Amsterdam has been 10 years in the making.”

Sjoerd Dijikstra, a spokesman for the Schoonschip development, explained how the floating housing development works: “The Schoonschip … development in Amsterdam has been 10 years in the making.”

He works in the materials industry for a company called Metabolic and “so I went to all of the suppliers of materials we use for building our houses to check that we had the most sustainable materials free of harmful chemicals and carcinogens. “

Metabolic is a partner in developing the Schoonschip houses. It was founded by Eva Gladek, born and raised in New York City, who began her career as a molecular biologist.[6]

Dyjikstra notes that Schoonschip is building the floating houses “at an industrial area outside of Amsterdam and then the houses are taken from the land by crane and lowered into the water where they are towed by boat to the development site inside a small Amsterdam canal…. Several of the 30 floating units have been split into apartments so there are actually a total of 46 units altogether. Soon my wife and I will be living in our own floating home. People need to like the water for this type of life. You live closer to the elements of wind and water and when the wind blows you feel the waves gently rolling the house. If you like the sea, it’s a great experience.”

He notes the floating houses are three stories high: “The bedrooms are located at the water line, the living room and kitchen and study in the second storey and an outdoor terrace on top.” The average home is 1,600 square feet and “will cost about 650,000 euros ( about $726,000) but this includes legal costs and the infrastructure to support the houses including electrical, water, sewage. The net cost would be about 450,000 euros (about $503,000). As we build more units the cost of construction will go down since we are sourcing our homes from a manufacturer who can reduce their costs with more unit construction and pass on some of the savings to the customer. I think there is a good chance of this since we have had a good public reaction and we have a long waiting list of people who want to order the floating homes.”

He noted that “We paid a great deal of attention to insulation and we used hemp to insulate the houses. The appliances are all electrical and we built an array of 33 solar panels to provide 10,000 kilowatts of electricity which is supported by a battery system to provide sustainable energy at night when the sun doesn’t shine. We also worked on air filtration so that the air you breathe is clean and free of emissions and chemicals.”

As housing is very expensive in Amsterdam, “apartments are expensive and small we offer a good alternative for middle income people who want to live close to Amsterdam and still enjoy being on the water with a sustainably built house that is not overly expensive and will cost less as we build more units.”

The Schoonschip Foundation is headed by Peer de Rijk (chair), Siti Boelen (treasurer), Marjan de Blok (secretary and initiator) and Marjolein Smeele (general board member and architect). [7]

BUOYANT HOUSES

Source: Buoyant Foundation

In Louisiana, the Buoyant Foundation Project (BFP), was “founded in 2006 to support the recovery of New Orleans’ unique and endangered traditional cultures by providing a strategy for the safe and sustainable restoration of historic housing.”

The foundation says: “Retrofitting the city’s traditional elevated wooden shotgun houses with buoyant (amphibious) foundations could prevent devastating flood damage and the destruction of neighborhood character that results from permanent static elevation high above the ground.”

A buoyant foundation “is a type of amphibious foundation in which an existing structure is retrofitted to allow it to float as high as necessary during floods while remaining on the ground in normal conditions. The system consists of three basic elements: buoyancy blocks underneath the house that provide flotation, vertical guideposts that prevent the house from going anywhere except straight up and down, and a structural sub-frame that ties everything together. Utility lines have either self-sealing ‘breakaway’ connections or long, coiled ‘umbilical’ lines. Any house that can be elevated can be made amphibious.”

Since 2006, the Buoyant Foundation says its mission “has broadened to apply not only to post-Katrina New Orleans but also to numerous other flood-sensitive locations around the world. The Buoyant Foundation Project is a registered non-profit organization in the State of Louisiana. The team consists of students, professors, and alumni of the University of Waterloo (Canada) School of Architecture.”[8]

The project founder is Elizabeth English, associate professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture in Cambridge, Ontario. She was formerly associate professor – research at the Louisiana State University (LSU) Hurricane Center. When not in Canada she resides in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, where she continues her research on hurricane damage mitigation strategies with particular application to post-Katrina New Orleans.[9]

FLOATING FARMS

In the Port of Rotterdam, a floating concrete barge has been constructed that contains a floating dairy farm to produce milk, yogurt and other dairy products.

Floating farm under construction at the Port of Rotterdam

A report in the American Journal of Transportation quoted Minke van Wingerden, a partner at Beladon BV – the floating farm builder, as saying that the original idea for the farm came from a visit to New York after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

At that time, she and her husband, Peter van Wingerden, saw that food supplies were disrupted for days in the New York and New Jersey areas after the hurricane hit. Flooding and road damage prevented trucks from making deliveries. This food supply and transportation disruption has been repeated during Hurricanes Katrina, Maria and mostly recently with Hurricane Michael in Florida in 2018.

The van Wingerdens began researching ways to improve food deliveries during such emergencies. Originally, they focused on supporting more urban or rooftop gardens, but instead shifted to a popular trend in the Netherlands to offset limited and expensive land by building floating houses and offices.

So, they decided to build a floating farm.

The floating farm, Minke van Wingerden said, can adapt to changes in the climate and be hurricane-resistant.

“You go up and down with the tide, or the water, and it has no influence on your food production, so you can still make fresh food in the city,” she said.

“During our research, we saw that many cities are built on or near the sea and along rivers and deltas just as we see here in the Netherlands. This gave us the idea for the floating dairy farm so that the food supply could be brought closer to cities and consumers using floating structures.”

Privately, while they applaud the innovation, some people in Rotterdam think that the dairy products from the floating farm will cost too much and will not compete with land-based dairy farms.

Van Wingerden concedes that the cost of producing milk products will be higher from a floating farm than from a land-based farm.

However, she argues that the Beladon floating farm will be located close to Rotterdam consumers, reducing transportation costs and providing fresher products with faster delivery times.

The added advantage is that the floating farm will have a much smaller CO2 foot print than conventional farms: “We will use solar panels to power the farm and use rain water from the roof to supplement our water supply.”

To reduce the environmental impact further: “We will be using existing food waste to feed our cows. There is a brewery nearby so we will use the beer broth that is a product of brewing beer and feed it to our cows. They love it. Another source of food for the cows is potato peels from a food processor. In both cases these waste products would be burned or dumped onto a garbage disposal site. Instead, we feed the product to our cows.”

She hopes that companies like Amazon, and its Whole Foods subsidiary, will find that the Beladon floating farm fits into their fast delivery and organic food business model: a new technological creation to source dairy and other farm products requiring only an urban pier base of operations.

Van Wingerden said the floating farm is estimated to cost 2.6 million Euros (about $2.9 million). Its dimensions are 30 meters by 30 meters or 89 feet by 89 feet.

The structure is built on a concrete floating base. The second deck is composed of a kitchen to mix the feed for the cows, a processing facility for milk and yogurt products and a shop to sell the milk products. The top deck will be the pasture for forty cows that is connected by a bridge to allow the cows to walk off the farm and on to a land-based pier space for more walk-around space.

Van Wingerden describes the floating farm as “a floating laboratory” for developing new food supplies closer to cities on sea coasts or adjoining rivers and lakes.

She believes Asia will be a major market for the floating farm because many cities are located close to a body of water. There, she sees China as a major market, not just because of the large population living by the coast, but also because of the cities located along rivers such as the Yangtze.

Beladon is also looking at markets in Europe and North America, especially along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Floating farms can help address rising demand for food by bringing farm production closer to consumers and providing sustainable advantages that lower the carbon foot print and provide an organic food product.

Beladon believes these advantages will mitigate the lower cost advantage of larger land-based farms, which rely on trucking and diesel-powered harvesting.[10]

CONCLUSION

The movement toward floating structures is growing and looking at how investing in sea level defense can also create new real estate development. The key is to inspire coastal cities and communities to build new houses, garages, farms and even cruise ship terminals (see rendering above) on the water.

The Netherlands, with its long history of reclaiming land and building dikes to defend against the sea, has now begun to build more floating structures that increase commercial value so as to offset the costs of sea level defense.

The Dutch example influenced the Buoyant House project’s investment into floating houses as a defense against flooding and sea level rise for coastal communities in Louisiana and around the world

Cities need to begin investing in new floating developments now, Koen Olthuis argues, or they will be threatened by rising seas and storm surges.

“In 20 years,” he adds, “cities are going to be different than they are today.”

NOTES

[1] Waterstudio.NL ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING & BUILDING ON WATER COMBINED PROJECT OVERVIEW SELECTION & COMPANY PROFILES (January 2019)

[2] https://www.scmdaleel.com/category/offshore-jack-up-rigs/213

[3] http://3kbo302xo3lg2i1rj8450xje-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/2016-0822-03-Move-out-01.jpg

4] https://www.macgregor.com/Products-solutions/products/port-and-terminal-equipment/floating-car-parks/

[5] http://schoonschipamsterdam.org/en/

[6] https://www.metabolic.nl/projects/schoonschip/

[7] http://schoonschipamsterdam.org/en/#mk-footer

[8] http://buoyantfoundation.org/about-us/

[9] http://buoyantfoundation.org/about-us/

[10] https://www.ajot.com/insights/full/ai-in-rotterdam-green-acres-meet-green-seas

Click here for the source website

Click here for the pdf