Vingt mille lieux sur les mers

By Frederic Joignot

Le Monde

Vinght mille lieux sur les mers: Comment les architectes voient la vie sur l’eau

Projet “Citadel” d’appartements, agence Waterstudio (Hollande). Il s’agit de construire dans des polders ouverts des habitations flottantes adaptées à la montée des eaux. C’est une “citadelle” parce qu’il s’agit “du dernier rempart contre la mer”, disent les architectes.

Un vieux rêve de l’humanité est de se réfugier sur une île pour y refaire sa vie, voire le monde, inventer une société meilleure, expérimenter des voies nouvelles pour l’humanité. C’est sur une île que Thomas More situait Utopia (1516), sa société idéale, au cœur d’une île encore que Tommaso Campanella imaginait la Cité du Soleil (1602) ou Sir Francis Bacon La Nouvelle Atlantide(1624), menée par les philosophes. Aujourd’hui, ces utopies insulaires sont rattrapées par la réalité terrestre : construire des cités écologiques sur des îles nouvelles est devenu un mouvement architectural. Né dans l’urgence de la menace environnementale, ce courant qui a gagné l’urbanisme interpelle, depuis dix ans, économistes, institutions internationales et gouvernements.

Ce mouvement a un drapeau – bleu, couleur des océans – et un pays pionnier : les Pays-Bas. Elu en 2007 parmi les personnes les plus influentes de l’année par le magazine Time, l’architecte Koen Olthuis, cofondateur de l’agence Waterstudio, à Ryswick, est l’un de ses praticiens et théoriciens. Il signe ses mails Green is good, blue is better (« le vert [le souci écologique], c’est bien, le bleu, c’est mieux ») et avance plusieurs arguments pour expliquer pourquoi construire sur les mers est une idée d’avenir : « D’ici 2050, 70 % de la population mondiale vivra dans des zones urbanisées. Or, les trois quarts des plus grandes villes sont situées en bord de mer, alors que le niveau des océans s’élève. Cette situation nous oblige à repenser radicalement la façon dont nous vivons avec l’eau. » Car, rappelle-t-il, les cités géantes du XXIe siècle sont mal en point : « La préoccupation “verte” qui saisit aujourd’hui architectes et urbanistes ne suffira pas à résoudre les graves problèmes environnementaux des villes. Comment allons-nous affronter les problèmes de surpopulation ? De pollution ? Résister à la montée des eaux ? » Sa réponse : en bâtissant des quartiers flottants, de nouvelles îles, en aménageant des plans d’eau pour un urbanisme amphibie. « La mer est notre nouvelle frontière », affirme l’architecte, détournant la formule de John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Car si l’espace manque sur terre, la mer est immense – et inhabitée.

Waterstudio n’est pas la seule agence néerlandaise à développer cette vision « bleue ». Plusieurs cabinets d’architecture et entreprises expertes, reconnues internationalement, bâtissent déjà sur l’eau. Il faut rappeler qu’aux Pays-Bas, contrée où l’on compte 3 500 polders et des villes sillonnées de canaux, s’adapter et résister aux assauts de la mer et aux inondations est une activité séculaire indispensable : en 1953, une violente tempête a causé près de 2 000 morts et provoqué l’évacuation de 100 000 personnes. Ce savoir-faire est devenu symbolique de la lutte de l’homme face à une nature menaçante, perturbée par le changement climatique. Désormais, « le monde est un polder », écrivait le biologiste Jared Diamond dans Effondrement. Comment les sociétés décident de leur disparition ou de leur survie (Gallimard, 2006).

Sauf que les polders, ces terres artificiellement gagnées sur l’eau, ne suffisent plus. Waterstudio a notamment conçu des maisons flottantes à IJburg, un quartier expérimental au sud-est d’Amsterdam. D’autres projets maritimes sont en cours. En 2009, l’agence a dessiné le projet Citadel, une cité flottante de 60 appartements installée dans un polder délibérément ouvert aux eaux. « Nous l’appelons Citadel, car ce sera la dernière ligne de défense contre la mer », explique Koen Olthuis, pour qui ce projet « montre clairement les possibilités infinies de la construction sur l’eau »

Au pays des polders, le fait de bâtir des immeubles flottants offre un complet renversement de perspective : « Nous cherchons à nous adapter à la mer, à l’accompagner, plutôt que lutter avec elle », explique l’architecte. Quand les habitations flottent, nul besoin de pomper l’eau, de renforcer en permanence les digues. Un nouvel urbanisme s’invente, où des quartiers entiers, jardins et maisons, reposent sur l’eau, parfois ancrés au sol, parfois mobiles. Une telle conception, avance l’architecte, va bouleverser toutes nos habitudes urbaines. Elle nous oblige à revoir « notre vision statique des villes » : la terre habitée ne sera plus tout entière « ferme ». Elle nous engage à repenser notre « exigence du sec » sur des territoires protégés par les digues, pour vivre sur l’eau. Elle annonce la multiplication d’habitats flottants et amphibies sur les zones côtières.

« Une ville plus mouvante, plus dynamique, se dessine. Certains habitats et services se déplaceront. L’urbanisme, la vie citadine vont en être transformés », conclut Koen Olthuis. Il n’est pas le seul à le penser. Du 26 au 29 août, signe des temps bleus à venir, se tiendra à Bangkok Icaade 2015, la première conférence internationale sur l’architecture amphibie. A Lagos, au Nigeria, l’architecte Kunlé Adeyemi a conçu une école flottante pour les enfants du bidonville de Makoko, sur la lagune. Posée sur des barils, équipée de panneaux solaires, elle a été inaugurée en février 2013. Kunlé Adeyemi prévoit de bâtir une flottille de maisons sur le même principe.

Les architectes de l’agence DeltaSync, à Delft, aux Pays-Bas, ont synthétisé ces idées dans un manifeste architectural et économique : « Blue Revolution ». Si les terres viennent à manquer, écrivent-ils, « où irons-nous ? Dans le désert ? Les ressources en eau manquent. Dans l’espace ? C’est toujours trop cher. Reste l’océan ». Notre planète de rechange est là. Car 71 % de la surface terrestre est maritime. Le texte continue : « Ce siècle verra l’émergence sur l’océan de nouvelles cités durables (…). Elles contribueront à offrir un haut standard de vie à la population, tout en protégeant les écosystèmes. Un rêve ? Non, la réponse au principal défi du XXIe siècle. »

L’agence DeltaSync, qui a construit en 2010 un pavillon flottant dans le port de Rotterdam, conseille le gouvernement néerlandais sur ses projets d’aménagement urbain, travaille sur la flottabilité et la stabilité de l’architecture aquatique. Elle développe avec l’université des sciences appliquées Inholland un projet de parc sur l’eau dans le port du Rhin, à Rotterdam : imaginez un petit archipel abritant un marché, une piscine, des restaurants, un centre de sport, une salle de concert. L’idée pourrait être reprise dans plusieurs villes néerlandaises, dans les ports ou sur des polders ouverts.

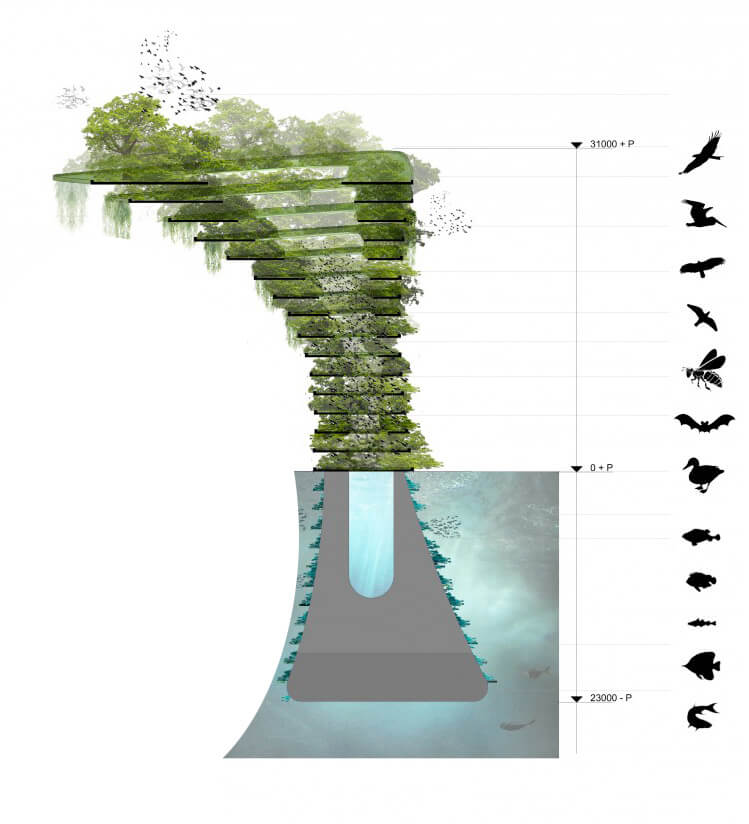

Un autre projet conçu pour un bassin portuaire est le Sea Tree, l’arbre de mer. Conçu par Waterstudio, encore dans les cartons, il révèle une autre dimension de l’architecture bleue : son exigence écologique. Il s’agit d’une haute structure en terrasses, entièrement végétalisée, construite selon les principes de la technologie offshore. Chaque grande ville côtière pourrait en installer. Ces arbres maritimes géants pourraient aider à lutter contre l’épuisement environnemental des grandes cités : ils comporteront des potagers verticaux et des terrasses plantées pour nourrir les citadins, ils capteront le CO2, ils abriteront quantité d’animaux utiles – oiseaux, abeilles, chauves-souris insectivores – qui rayonneront sur la côte et la ville proche. A Manhattan, à Singapour, les municipalités réfléchissent sérieusement à en installer, assure-t-on à Waterstudio.

On retrouve, dans ce projet de tour portuaire, plusieurs des idées-forces du courant dit de l’« architecture écologique », en plein essor. C’est un autre volet stratégique de la construction « bleue » : récupérer et consolider les principes de la construction « verte ». Autrement dit, s’appuyer sur les énergies durables (éolien, solaire, chauffage passif, géothermie), végétaliser les terrasses et les toits, intégrer les immeubles à l’écosystème local, s’inspirer des formes naturelles. L’architecte malaisien Ken Yeang, l’un des théoriciens de cette écoarchitecture, auteur de The Green Skyscraper (« Le gratte-ciel vert », non traduit, Prestel, 1999), a poussé cette réflexion très loin : selon lui, un immeuble doit être conçu dès l’origine comme un « système vivant construit », afin de pouvoir entrer « en symbiose » avec son environnement : sobre en énergie, recyclable, bioclimatique, l’habitat doit participer du cycle naturel, réintégrer la biosphère et dépolluer, tel un arbre colossal.

Pour bâtir cette cité aquatique, il faudra d’abord concevoir des grands caissons flottants de différents formats qui s’emboîteront jusqu’à former des îlots constructibles. Les premières unités doivent être mises en chantier cette année. Les commanditaires ont hâte de les tester : la pollution des grandes villes chinoises est telle que les autorités envisagent de construire rapidement à l’écart des zones atteintes. Sur l’eau, en face des cités enfumées. Demain, ces cités pourraient abriter une partie de la population littorale, désengorger les mégapoles, être économes en énergie, alléger la dégradation environnementale

Que répondent les architectes « bleus » à ces critiques et à ces risques d’une pollution aggravée ? Ils soulignent qu’ils ne veulent pas construire des îles artificielles, mais flottantes, qui n’altéreront pas les fonds marins. Et ils avancent un nouvel argument de poids : au XXIe siècle, l’humanité (9,6 milliards d’habitants attendus en 2050) va rencontrer de graves problèmes de terre arable, d’épuisement des stocks halieutiques et d’alimentation – toutes choses qui inquiètent beaucoup l’Organisation des Nations unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture (FAO). A Londres, pour les concepteurs de la Floating City, la cause est entendue : seule une future « colonisation » des mers permettra d’arrêter la conquête des terres par la ville. Ils écrivent : « La biologie terrestre a été soumise depuis longtemps à une exploitation si intensive que les terres encore inexploitées doivent être préservées de l’urbanisation. De nouvelles colonies maritimes devront être planifiées au XXIe siècle. »

C’est sur cette problématique de la disparition et de l’épuisement des sols, associée à une crise alimentaire, que les défenseurs de l’urbanisme marin rejoignent un autre volet de la « révolution bleue » : la croissance exponentielle de l’aquaculture mondiale depuis vingt ans. En 2008, selon un rapport de la FAO, l’aquaculture a fourni 46 % des poissons à l’échelle mondiale. Il s’agissait à 87 % de poissons d’eau douce, mais l’aquaculture marine est en progression constante, ainsi que l’algoculture et la conchyliculture (élevage des mollusques marins). Cela se comprend : la pèche industrielle menaçant d’épuiser les stocks de nombreux poissons, l’aquaculture apparaît comme une réponse viable pour nourrir les populations, même si elle rencontre de sérieux problèmes de gestion durable.

Or, les architectes bleus avancent que l’avenir de l’aquaculture maritime passera par l’édification de fermes et de bassins nourriciers à proximité des cités côtières. C’est l’idée qui est derrière un projet de l’agence DeltaSync, « Floating food cities will save the world » (« les villes alimentaires flottantes sauveront le monde »), développé par l’ingénieur Rutger de Graaf. Imaginant une nouvelle forme d’économie circulaire, il explique que la construction de récifs artificiels accueillant poissons et crustacés, de bassins d’aquaculture aquaponique recyclant les éléments nutritifs apportés par les déchets des villes flottantes, et d’îles agricoles permettra de nourrir les populations urbaines côtières. Selon lui, il suffirait que 1 % des mers soient consacrées à l’aquaculture pour nourrir l’humanité – le reste des eaux devant être sanctuarisé. Une étude de faisabilité accompagne ces projets

Les partisans de l’architecture « bleue » avancent enfin qu’elle devrait permettre d’éviter un des drames possibles du changement climatique : la submersion de nombreuses îles du fait de la montée des eaux. Le gouvernement des Maldives y croit, qui a lancé en 2010 un programme de constructions sur l’eau afin d’accueillir les populations menacées et de sauver le tourisme : des projets de villages amarrés mais aussi d’îlots de plaisance, d’hôtels et de golfs flottants sont à l’étude. Ces réalisations pionnières, encore très élitistes − « Les riches paient pour les prototypes qui serviront à tous », explique Koen Olthuis –, sont étudiées de près par les Etats insulaires d’Océanie, qui ont lancé en juillet 2014, lors du 45e Forum des îles du Pacifique, un appel de détresse aux pays industrialisés.

Ils ont rappelé que l’archipel de Kiribati, où vivent 110 000 personnes, risque de devenir inhabitable en 2030 – même si certains scientifiques assurent que les atolls vont s’élever avec les mers. Les autorités ont d’ores et déjà acquis 2 400 hectares dans les îles Fidji pour les reloger. Le président de la République des Kiribati, Anote Tong, a aussi évoqué la possibilité de construire une « île flottante » pour les futurs réfugiés climatiques. Or, deux projets de ce type existent dans les cartons des architectes bleus. Le premier, un ensemble de trois îlots végétalisés, agricoles, supportant une tour d’habitation géante, est étudié par le constructeur japonais Shimizu Corp.

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS