In the Market for a Hyper-Luxurious Floating Island?

Biscayne Times, Erik Bojnansky, July 2014

A Dutch company has submitted plans to anchor 30 artificial floating islands in Maule Lake, a privately owned lake in North Miami Beach. Maule Lake lies east of Biscayne Boulevard, adjacent to the Aventura community of Point East, the North Miami Beach neighborhood of Eastern Shores, and the twin 24-story towers of Marina Palms Yacht Club & Residences, currently under construction at 172nd Street and the Boulevard.

The project’s name: Amillarah Private Islands — North Miami Beach. The project’s developer: Dutch Docklands USA, a company owned by Frank Behrens, chairman of the Miami Dutch Chamber of Commerce.

Behrens didn’t return several phone calls for comment, but in August 2013, he told Miami Todaythat his company was considering a body of water somewhere in Miami-Dade County as the site to unveil Dutch Docklands’ floating-home concept in the United States.

“You can create whole new communities, and because it’s floating and on the waterfront, it would mean very high-end real estate,” he told the weekly newspaper. “You can create private beaches, private islands. Those big projects could be easily realized in Miami and would be fantastic attractions.”

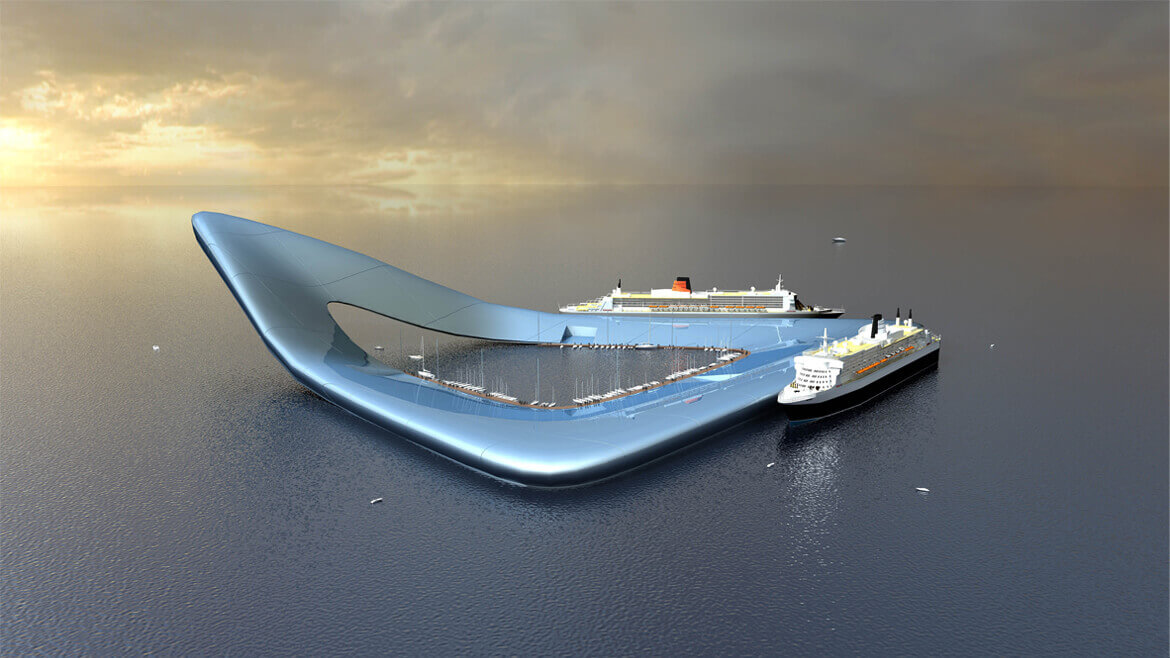

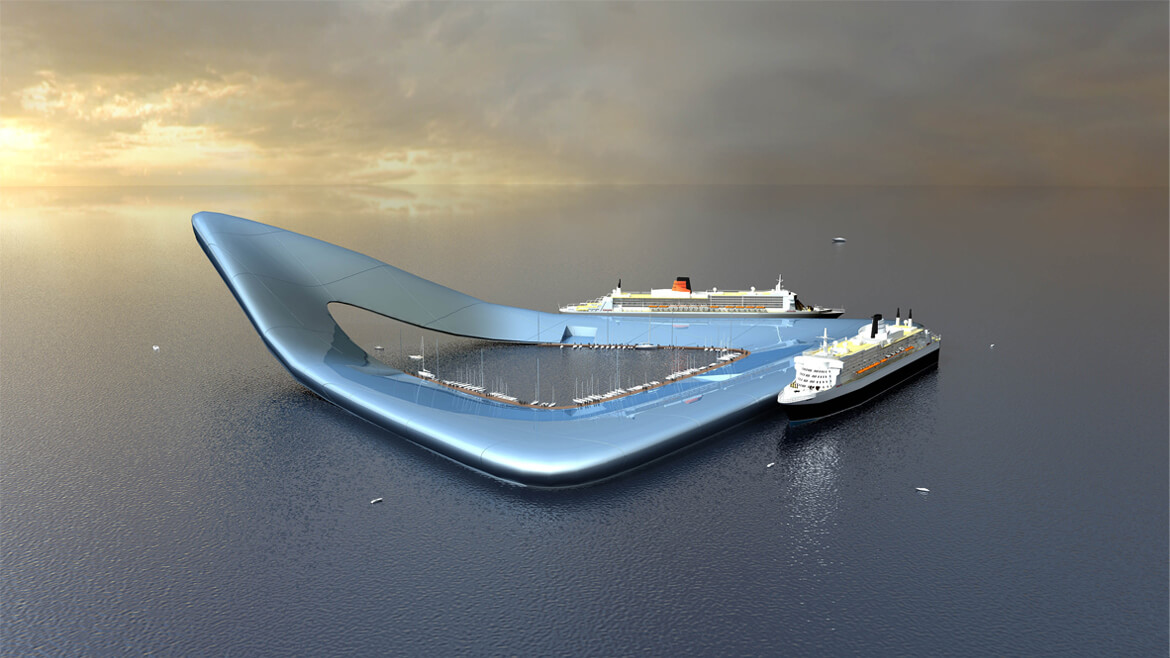

Dutch Docklands, based in Delft, the Netherlands, is the parent company of Behrens’s U.S. subsidiary. The award-winning firm, which specializes in floating technologies and design, was founded in 2005 by real estate developer Paul H.T.M. van de Camp and Koen Olthuis, an architect who has made a career designing luxury homes and other floating structures via his architecture firm Waterstudio. Olthuis also has patents for floating foundations strong enough to hold dozens of homes, roadways, cars, and parks, even cruise ship terminals.

Utilizing Olthuis’s patents, Dutch Docklands is designing a floating apartment complex for South Holland, re-engineering the floating islands for Dubai’s Palm Island project, and building a series of floating projects for the Maldives. In fact, the proposed floating islands within Maule Lake are named after another Dutch Docklands project, Amillarah, in the Maldives. The word amillarah means private island in Maldivian, according to Dutchdocklands.com.

Maule Lake, with direct access to the Intracoastal Waterway and the ocean, covers 174 acres and has a deep bottom that can accommodate yachts up to 100 feet long, according to a real estate website.

Under the plans Dutch Docklands submitted to the City of North Miami Beach on June 26, the Maule Lake version of Amillarah would consist of 29 manmade, anchored islands, each of which would include a two-story, four-bedroom villa, a patio, garden, sandy beach, swimming pool, rooftop terraces, al fresco dining areas, and two boat slips. A 30th island would be an “amenity island” staffed 24 hours a day for the exclusive use of residents and their guests.

If the project moves forward, all 30 of the islands, co-designed by Waterstudio and Coconut Grove-based Bermello Ajamil & Partners, would be constructed offsite and transported to Maule Lake.

Boats would be an essential element for the islanders: Each island would be at least 500 feet from shore and about 80 feet from its nearest neighbor.

Another interesting feature of Amillarah Private Islands: They would be off the grid.

“Dutch Docklands have designed the floating islands to be virtually self-sustaining,” according to Greenberg Traurig environmental attorney Kerri Barsh, a lobbyist for Dutch Docklands in a letter to Carlos Rivero, North Miami Beach’s acting planning director.

“By deploying cutting-edge technology and sustainable building designs, Dutch Docklands will eliminate the need for the floating islands to connect to existing potable water supplies, waste water collection systems, or to electric utilities,” her letter states.

Freshwater would be provided by “collectors and advanced filtration systems,” according to the letter. Solar panels and “hydrogen-powered generators” would provide electricity. Solid waste would be gathered by a private contractor and a special vessel “will be kept ready at all times for the exclusive use of municipal emergency responders.”

As for the disposal of human waste, each of the 6900-square-foot villa islands, and the 6800-square-foot amenity island, would be equipped with a “biological sewage facility” to “address wastewater and sewage consistent with U.S. EPA regulations.”

Perhaps the best news for a city in search of additional revenue, the letter points out, is a U.S. Supreme Court decision last year that floating homes are “akin to real property and not vessels,” and thus can be taxed. (The case was brought by North Bay Village resident Fane Lozman against the City of Riviera Beach, which demolished his houseboat.)

Since the islands will be marketed to affluent islanders who will live on Amillarah only “40 percent of the time,” there will be few, if any, floating homeowners claiming a homestead exemption.

“Assuming each residential island is appraised at a value of $12.5 million and applying 2013 millage rates,” according to Barsh’s letter, “we anticipate that the project will generate approximately $2.8 million annually in [property] tax revenue for the city.”

But for Amillarah to happen, part of Maule Lake will need to be rezoned, Barsh noted. North Miami Beach’s swath of Maule Lake is currently designated “as an open water and transportation corridor.”

Thus Barsh is asking for PUD-3 zoning for a 39-acre section of the 174-acre lake. Under PUD-3, a developer could construct up to 1941units in buildings as tall as six stories on 39 acres. With bonuses, a developer could create 2911 units in towers up to 12-stories in height on PUD-C zoned land. (Development is not permitted in Aventura’s sliver of Maule Lake, which the city refers to as a “conservation district.”)

Dutch Docklands USA still needs to close on its contract to buy the lake from a trusteeship headed by Raymond Williams, a descendant of E.L. Maule, founder of the Maule Rock Mining Company.

During the early 20th Century, 60 train carloads of limestone rock each day were mined from what is now Maule Lake, and used to construct roads, bridges, and buildings in Dade and Palm Beach counties. The limestone also served as ballast for Henry Flagler’s railroads before being replaced with granite, says local historian Seth Bramson. Maule Rock Mining wasn’t alone. Ojus Rock Mining Company, owned by A.O. Greynolds, was extracting rock from the earth just a mile west of Maule’s mine. Sometimes the competition turned nasty. In January 1921, Ojus Rock Mining took out an ad in the Miami News claiming that Maule’s rock was shoddy.

Eventually, Maule’s rock pit became a lake. “When you go down to a certain level in South Florida,” Bramson explains, “you hit water.”

Whereas Greynolds gave his rock mine to the county for Greynolds Park (see “Green Piece,” June 2013), Maule Rock Mining sold chunks of its 300 acres to real estate developers and to the state (for highways). In 1957, Maule Lake was dredged for fill for the creation of Eastern Shores.

Brackish water flows in and out of Maule Lake via Snake Creek, the Oleta River, and neighboring Dumbfoundling Bay. So, too, does aquatic life. Snook, catfish, and tarpon have been fished at Maule Lake for decades. The lake was even used in a few scenes for the hit show Flipper, according to a 1964 Miami News article.

Maule Lake was popular for boat racing, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. But in 1991 the state enacted strict speed limits at the lake to protect manatees. Between 1974 and 1993, 19 dead manatees were found in or near Maule Lake, according to the Miami Herald.

Since 1998, Patrick Killen, commercial director of Keller Williams Elite Properties, and his wife Karen, broker/owner of The Villas, LLC, have been trying to sell Maule Lake on behalf of the Williams trust. (In this pending deal, Patrick Killen is representing the potential buyer, Dutch docklands. Karen Killen represents the seller.)

A picture of Maule Lake adorns the top of Patrick Killen’s Facebook page. At one point, according to Killen, Donald Trump was under contract to buy Maule Lake so he could fill it in and build a high-rise there.

“I think most people don’t know that it’s a private lake,” Patrick Killen says. “For whatever reason, it’s not common knowledge.”

Maule Lake is not only private, it is pricey. Four years ago the asking price was $17 million. More recently it was listed at $19.5 million, says Killen.

Maule Lake will be a nice fit for Amillarah, explained Barsh in her letter to the city. The lake’s depth of 22 feet means it’s unlikely that “sensitive environmental resources” will be present at the bottom. Then there’s the fact that North Miami Beach and Maule Lake happen to be in South Florida.

“No place in the United States is as vibrant and exciting as South Florida,” Barsh notes in her letter. And no place in the U.S. is as threatened by sea-level rise, she adds.

In as few as 50 years, low-lying areas, such as Eastern Shores, Keystone Point, and Sans Souci Estates, may be regularly flooded during high tide. (See “Lost in a Rising Sea,” September 2012.)

For this reason, Amillarah is not just a quirky, alternative lifestyle — it’s also the future of development in South Florida, according to Barsh, writing that “Dutch Docklands believes its technology will help address some of the threat of sea-level rise. By choosing North Miami Beach for its first project in the United States, Dutch Docklands hopes its approach can become a model for the whole of South Florida and the world.”

Whatever Dutch Docklands’ intention, Marina Palms developer Neil Fairman can’t help but like the company’s top executives. Fairman says he met them a few months ago and was struck by their agreeable demeanor. Among other things, they assured him that their project won’t interfere with the operation of Marina Palms’s 112-slip marina.

“They seem like nice people, and they seem very soft-spoken and ready to cooperate with the community,” he says. As for the project itself, Fairman says, “I think it’ll be very cool.”

Eerste City App klaar voor inzet in sloppenwijk

Architectenweb, June 2014

De Stichting Floating City Apps presenteert de eerste concretisering van het City Apps-concept, bedacht door architect Koen Olthuis. De Communication App is een drijvende eenheid die in waterrijke sloppenwijken een sociale of educatieve rol kan spelen.

De City Apps zijn drijvende eenheden, gebaseerd op een standaard zeecontainer op een drijflichaam, en kunnen verschillende functies vervullen. De eenheden zijn door Koen Olthuis van architectenbureau Waterstudio.NLbedacht om op relatief eenvoudige manier de leefomstandigheden in sloppenwijken aan en op het water, zogenoemde wetslums, te verbeteren.

De Stichting Floating City Apps presenteert de eerste concretisering van het City Apps-concept, bedacht door architect Koen Olthuis. De Communication App is een drijvende eenheid die in waterrijke sloppenwijken een sociale of educatieve rol kan spelen.

Vorige maand is de Communication App met tablets en twee grotere beeldschermen getest door een schoolklas van 25 kleuters. Het digitale klaslokaal functioneerde succesvol, volgens de Stichting Floating City Apps. De Communication App is nu klaar om te worden ingezet, wat waarschijnlijk binnenkort in de Filippijnen gaat gebeuren.

Drijvende functie-uitbreidingen

De City Apps zijn drijvende eenheden, gebaseerd op een standaard zeecontainer op een drijflichaam, en kunnen verschillende functies vervullen. De eenheden zijn door Koen Olthuis van architectenbureau Waterstudio.NL bedacht om op relatief eenvoudige manier de leefomstandigheden in sloppenwijken aan en op het water, zogenoemde wetslums, te verbeteren.

Olthuis vergelijkt de City App met de functie-uitbreiding van de smartphone. De sloppenwijk is de hardware; de installatie van City Apps voegt daaraan functies toe. Verschillende drijvende uitbreidingen kunnen de wetslum voorzien van energie, sanitaire voorzieningen, waterzuivering of een leslokaal.

De nu gerealiseerde Communication App dient als een sociaal en educatief platform. Tablets zijn verwerkt in wandmeubels, die zijn vervaardigd uit solid surface-materiaal, dat sterk en ongevoelig voor vocht en vuil is en kwalitatief fraai oogt. De Communication App geeft de bewoners van de sloppenwijk toegang tot internet en daarmee mogelijkheden als particulier ondernemerschap of leren in groepen.

Flexibel inzetbaar

Volgens de architect bieden de City Apps in het algemeen kleinschalige ‘bottom-up’ oplossingen , afgestemd op de behoeften in een specifieke wetslum. Daarbij zijn ze flexibel inzetbaar: er hoeven geen (al dan niet omvattende) projectplannen te worden ontwikkeld, maar er kunnen steeds aanpasbare en herbruikbare eenheden worden ingezet. Als ze niet meer nodig zijn, kunnen ze eenvoudig worden verplaatst naar een andere locatie.

Het idee is een uitwerking van de inzending App-grading Wet Slums, waarmee Waterstudio.NL in 2012 de Architecture & Sea Level Rise Award heeft gewonnen. Vorig jaar hebben Olthuis en Menno van der Marel de Stichting Floating City Apps opgericht om daadwerkelijke implementatie van de drijvende eenheden in wetslums wereldwijd te verwezenlijken.

Koen Olthuis’s Floating Krystall Hotel to Sparkle off the Coast of Norway

Inhabitat, Beverley Mitchell, August 2014

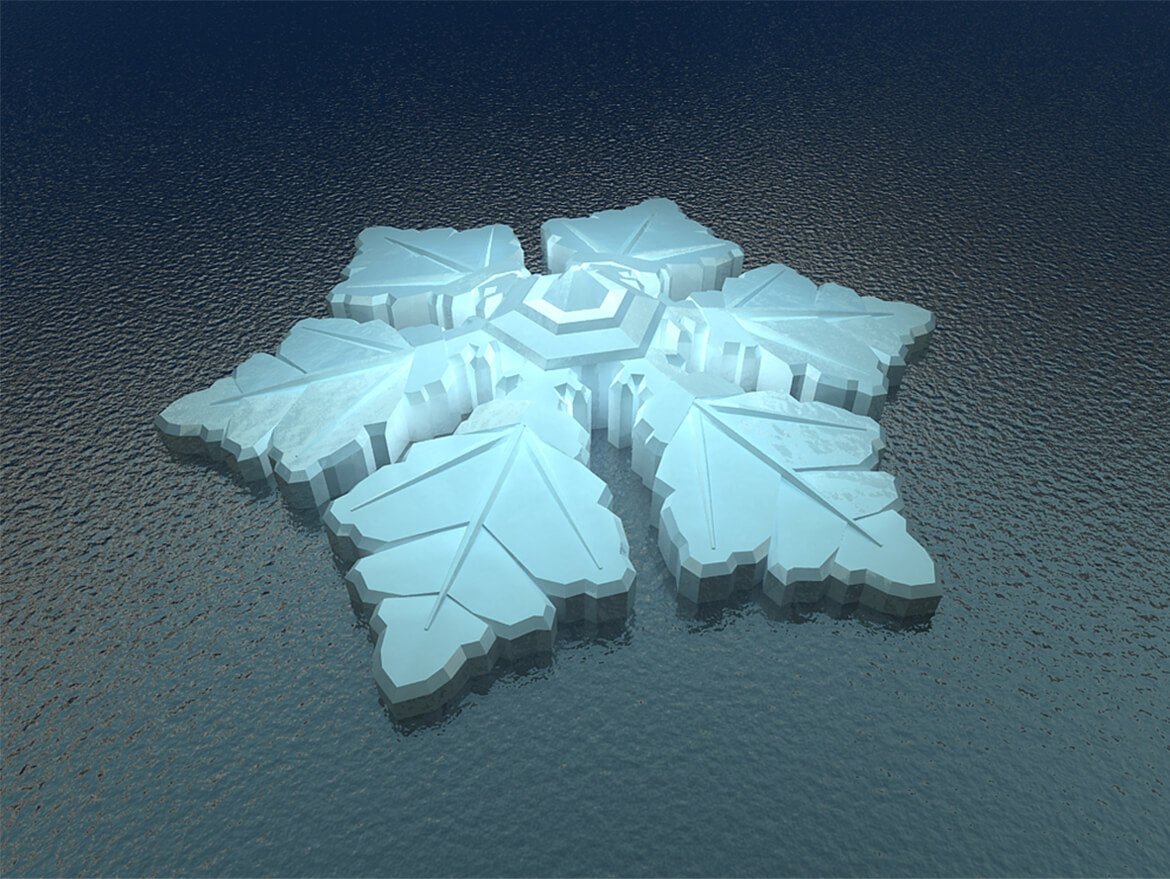

Koen Olthuis and Dutch Docklands have announced a new project: a five-star floating hotel off the coast of Norway named the Krystall. Reminiscent of their Maldives development the Greenstar, this cold-climate sister project will take the form of a six-pointed ice crystal. As with Dutch Docklands’ other floating structures the development will be low-impact, and it’s designed to “blend in with the ‘winter environment’ between the most beautiful fjords.”

The Krystall will float offshore from the northern city of Tromso, located within the Arctic Circle. Designed to be completely self-supporting and self-sustainable, the hotel will have a diameter of 120 meters, and facilities will include 86 guest rooms, conference rooms, and spa and wellness facilities. It’s also billed as a perfect spot for viewing the Northern Lights due to its glass roof.

The five-star luxury and spectacular nature of the project is aimed at attracting wealthy visitors from Japan, Russia and Europe. As Olthuis told CNN, “In the hotel, you’ll float through hallways lined with cool, futuristic blue shapes, recline by a fireplace faced in transparent bricks resembling ice blocks and sleep in rooms tricked out in minimalist, winter-themed designs.” But true to Olthuis’s green principles, the design is not just about the aesthetics. To be built in dry dock and then positioned in place, the hotel will not leave a lasting footprint on its location. “That’s the only way to bring a hotel to such a precious and beautiful marine environment,” he says.

Floating structures are a pragmatic design concern for the development company, as they ameliorate the risks to coastal properties associated with rising sea levels. As Olthuis explains, “We live in a dynamic world where static buildings do not bring us the needed flexibility. Building on water brings us new space for expansion, safety against floods and flexibility to adjust developments without demolition whenever needed.” The hotel is set to open in December 2016.

Flood risk and amphibious architecture

Rough guide to sustainability, Brian Edwards, 2014

This latest edition of Rough Guide to Sustainability remains a simple, no-nonsense reference source for all students and practitioners of sustainability in the built environment. It sets out the broad environmental, professional and governmental context underlying sustainability principles, and outlines the science, measures and design solutions that must be adopted to meet current definitions of responsible architecture.

The fourth edition covers the latest developments in a rapidly expanding sector. It offers a wider international scope than ever before, and includes new information on the role of BIM in sustainable design, assessment tools and techniques, and the RIBA Plan of Work 2013. Brand new material also discusses the impact of the latest legislative, social and technological developments.

Now in full colour and extensively illustrated throughout, this guide is essential reading for design and built environment students and professionals – and anyone keen to cut through to the facts about sustainability.

Devorar el mar

La Vanguardia Magazine, Eva Millet, May 2014

En el 2001 se sumergió la primera piedra de la llamada Palm Jumeirah: la más pequeña de las tres islas artificiales del proyecto Islas Palm, frente a la costa de Dubái. El emirato del golfo Pérsico empezó el siglo XXI inmerso en un frenesí constructor que no sólo preveía dominar el desierto y levantar el edificio más alto del mundo, sino también expandirse hacia el mar. En un lugar donde hasta hacía poco la hoja de palmera era el material constructivo básico, la silueta de este árbol, incrustada sobre el agua, formando la primera de las islas, se convirtió en una demostración de fuerza para unos y de megalomanía para otros.

En el 2001 se sumergió la primera piedra de la llamada Palm Jumeirah: la más pequeña de las tres islas artificiales del proyecto Islas Palm, frente a la costa de Dubái. El emirato del golfo Pérsico empezó el siglo XXI inmerso en un frenesí constructor que no sólo preveía dominar el desierto y levantar el edificio más alto del mundo, sino también expandirse hacia el mar. En un lugar donde hasta hacía poco la hoja de palmera era el material constructivo básico, la silueta de este árbol, incrustada sobre el agua, formando la primera de las islas, se convirtió en una demostración de fuerza para unos y de megalomanía para otros.

En Panamá, la llamada Cinta Costera, 26 hectáreas de terreno ganadas al mar, es ya una realidad: incluye una nueva autovía y numerosas zonas verdes. En el Mediterráneo, el Principado de Mónaco, un densísimo paraíso fiscal con mucha demanda de vivienda, ha decidido seguir ganando terreno al mar en este siglo, creando un nuevo barrio en la zona de Portier. En total, una superficie de seis hectáreas que incluirá una lujosa zona residencial y comercial y una marina para los yates.

El proyecto, una apuesta personal de Alberto II, el actual príncipe, ha sido otorgado a una constructora francesa y a tres despachos de arquitectura, entre los que destaca el del premio Pritzker Renzo Piano. No han trascendido planos ni imágenes virtuales, pero se sabe que la inversión superará los mil millones de euros y el proyecto se completará hacia el 2024. Una iniciativa similar, del doble de extensión, fue diseñada en el 2008 por los también arquitectos estrella Daniel Libeskind y Norman Foster. Se abandonó la idea debido a la crisis financiera mundial y, también, a motivos medioambientales.

El medio ambiente no parece ser una preocupación en los Emiratos Árabes: para sentar las bases de las dos primeras Islas Palm se requirieron casi 300 millones de metros cúbicos de arena, dragada del fondo del mar. Las obras fueron tan agresivas que, según diversos estudios realizados, se ha dañado de forma casi irremediable el ecosistema marino, además de llenar de cieno las otrora cristalinas aguas del golfo de Dubái.

La tercera fase, la llamada Palm Deira, precisó un volumen aún mayor de materiales, mientras que el archipiélago El Mundo (300 islas artificiales que conformaban la silueta de los países del planeta) arrojó otro gran número de toneladas de piedras y arena al fondo del mar antes de pararse, también por causas financieras, pero no medioambientales.

De todo lo desarrollado en menos de una década en el mar frente a Dubái, solamente está habitado el Jumeirah, donde se construyeron –y vendieron a precios astronómicos– decenas de villas y apartamentos. Según el diario inglés ‘The Daily Telegraph’, sus residentes se quejan hoy de las igualmente astronómicas facturas de electricidad que pagan por el aire acondicionado, que han de tener encendido de forma casi permanente. También se han dado problemas ocasionales con la fontanería que les han obligado, en más de una ocasión, a utilizar los baños públicos de uno de los centros comerciales existentes. La Palmera cuenta, por supuesto, con varios de estos complejos, además de las marinas y los hoteles de lujo que se publicitaron con el proyecto.

Lujo es un sustantivo que se repite constantemente en la actual tendencia de construir sobre el mar. En el siglo XXI vivir sobre el agua es signo de exclusividad. Algo chocante si se tiene en cuenta que (Venecias aparte) a lo largo de la historia, este hábitat ha sido sinónimo de precariedad. En Asia, los más pobres, los marginados, son quienes han vivido tradicionalmente mecidos por las mareas: como los tankas, que habitan en juncos en las zonas costeras del sur de China, Hong Kong y Macao y a quienes se les llama “los gitanos del mar”. En el Pacífico, los bajaut laut o “nómadas del mar” son una tribu remota y pobre que habita en barcazas de las que prácticamente no descienden o en cabañas construidas sobre postes a varios kilómetros de la costa.

El sistema de los postes ha sido copiado en muchos centros turísticos de lugares como la República de las Maldivas, donde las ristras de coquetos bungalows sobre las aguas del Índico se han convertido en sinónimo de vacaciones soñadas. Abundan en todo este país, compuesto de 1.200 islas, y es un modelo que se ha exportado a otros destinos similares.

Ahora, en una vuelta de tuerca, el Gobierno de Maldivas ha puesto en marcha un proyecto bautizado Las 5 Lagunas, que pretende urbanizar cinco atolones del paradisiaco archipiélago con infraestructuras flotantes. Se promoverán desde viviendas de lujo e islas privadas hasta un campo de golf y un centro de congresos, todo flotante. El proyecto se ha encargado a la empresa holandesa Dutch Docklands, especializada en estructuras de este tipo.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

El arquitecto del proyecto es el también holandés Koen Olthuis, cuya compañía, Waterstudio, se describe como la primera firma de arquitectura dedicada en exclusiva a “vivir en el agua”. Olthuis, de 42 años, se define como un pionero en “un nuevo mercado” que lleva la arquitectura “más allá de la costa, creando nuevas posibilidades flotantes para ciudades en crecimiento por todo el mundo”. La prognosis, explicada desde Waterstudio, es que, hacia el 2050, aproximadamente el 70% de la población mundial va a vivir en áreas urbanizadas. Dado el hecho de que el 90% de las ciudades más grandes del mundo está en la costa, “hemos llegado a una situación en la que estamos obligados a replantear el modo en el que vivimos con el agua”.

Contactado telefónicamente Olthuis, pionero de las islas flotantes, mientras se encontraba de vacaciones en la sólida Mallorca, explica que para él, construir sobre el mar es tanto una moda como una necesidad. “Expandir la ciudad hacia el mar, en casos como Nueva York, Tokio, Hong Kong o Singapur, ciudades cada vez más densas y pobladas, ha sido una necesidad”, explica. “Pero en el futuro las ciudades necesitarán más flexibilidad: las urbes cambian constantemente, por lo que lo interesante sería hacer ciudades flexibles, en el agua: edificios flotantes con distintas funciones, que puedas mover con bastante rapidez según las necesidades”, señala.

Olthuis añade que, dado que cada vez son más la urbes amenazadas por las subidas del agua, si se apuesta por construir edificios que floten, el peligro de inundaciones se minimiza. “Así que creo que construir sobre el mar se basa en tres cosas: la seguridad, el espacio y la flexibilidad –resume–. Aunque también hay una moda, una tendencia, porque los arquitectos y los urbanistas e, incluso, los gobiernos, vemos las posibilidades del agua. Cada vez hay más gente que se interesa por el tema!”.

La idea holandesa resulta, como mínimo, más discreta, comparada con los megaproyectos de Dubái, la isla artificial de Yas, en Abu Dabi (un monumental parque temático y comercial que se empezó a construir en el 2006) o la ambiciosa Pearl City, en marcha en Kuwait (una ciudad que quiere llevar el mar al desierto).

Olthuis asegura que fabricar las estructuras flotantes fuera del sitio y anclarlas al fondo marino es altamente sostenible. “Si un siglo después sacas nuestro proyecto –afirma–, no quedarán cicatrices en el paisaje, porque son edificios flotantes. No hay obras, no vertemos toneladas de arena ni dañamos el medio ambiente. Y eso es lo que el Gobierno de las Maldivas busca, porque no quiere estropear lo que atrae a la gente a la islas”.

Los promotores también recuerdan que el archipiélago podría ser uno de los primeros países del mundo en desaparecer por el aumento de los niveles del mar. “Por eso, para ellos, es esencial introducir nuevos modos de construir ciudades sobre el agua”, reiteran los diseñadores holandeses. Que este proyecto es casi la solución a la amenaza del cambio climático se repite como un mantra en la información (tanto gubernamental como privada) sobre él. Aunque, si las aguas suben debido el calentamiento global, no parece que la respuesta más efectiva sea construir villas para multimillonarios en lugares vírgenes como las Maldivas o en islas artificiales como las de Dubái… Pese a la diferencia de escala, en ninguno de los casos aparece la supuesta función social de la arquitectura.

“Sí, es cierto que lo que estamos haciendo en Maldivas está dirigido, por un lado, a los superricos, a la gente que podrá pagarse esas viviendas –admite Olthuis–. Sin embargo, todos los conocimientos tecnológicos que ganamos con estos proyectos podrán aplicarse a otros con función social. Estamos en conversaciones con el Gobierno de Maldivas para llevar a cabo un plan de vivienda asequible para la población de la capital, donde hay serios problemas causados por la densidad”.

Pero estos argumentos no convencen a todos. “Unas islas flotantes son turismo masivo”, asegura, rotunda, Pilar Marcos, la responsable de la campaña de costas de Greenpeace España. “Los atolones son espacios coralinos, supuestamente protegidos, y como no tienen prácticamente terreno, ya que la franja costera es nula para el desarrollo urbanístico, se ha ideado este sistema de chalecitos flotantes que, aunque parezcan muy monos, tienen un impacto que es brutal”, agrega.

Las organizaciones ecologistas como Greenpeace denuncian la mercantilización del medio natural en todo el mundo, donde el mar abierto parece ser la nueva frontera. “No conformándonos con destruir la primera línea de costa, como se ha hecho en España, ahora vamos a ir a ganar terrenos al mar”, denuncia Marcos. Para Greenpeace, casos como el de Dubái, que han tenido unas nefastas consecuencias medioambientales, ya han demostrado que al mar es mejor dejarlo tranquilo. “Se acude a él tratando de buscar más espacio o una confortabilidad en una zona que, como Dubái, es una locura, por la ausencia de agua y de recursos naturales… Es algo aberrante: el querer convertirse en destino turístico a toda costa y que pague el medio ambiente”, indica.

Marcos señala que con estos proyectos, a menudo justificados por motivos económicos, se hace caso omiso al propio sector turístico, que demanda cada vez más espacios protegidos y no masificados. Además, en el Índico, señala, la presencia de nuevas infraestructuras, como casas y hoteles, hace que se pierden las características naturales del mar, “que ya no va a ser tan cristalino como antes…; el desarrollo de los recursos naturales no nos va a sacar de pobres”, concluye. ¿Aunque se insista en su sostenibilidad?

Con esto, advierte la activista de Greenpeace, hay que ir con muchísimo cuidado, pues a la clásica justificación económica para mancillar el medio natural, hoy se le suma la tendencia del ‘greenwashing’, literalmente, “lavado en verde” o vender como ecológico y sostenible algo que no lo es, esté en el Mediterráneo, en el desierto de Dubái o en un atolón de las Maldivas.

‘Bouwen op water biedt ongekende mogelijkheden’

Het hele Westland, Paul van Delft, May 2014

Bouwen op water biedt een heel nieuwe dimensie aan de bouwwereld. Na de uitvinding van de lift, die verticale bouw mogelijk maakte, vormt het water een bron van nieuwe mogelijkheden. Lang leek het er op dat in de architectuur alles allang bedacht en uitontwikkeld was, maar dat blijkt niet zo te zijn. Bouwen op water geeft flexibiliteit, is milieuvriendelijk, biedt bescherming tegen datzelfde water en opent ongekende ruimtelijke mogelijkheden. Architect Koen Olthuis, die met zijn Architectenbureau Waterstudio wereldwijd actief is met bouwen op water, vertelde leden van VNO-NCW Westland en Jong Management Westland erover.

Historie

Olthuis schetste kort de historie van het bouwen. Al eeuwenlang worden statische, niet-flexibele gebouwen gerealiseerd. Ze zijn niet verplaatsbaar en niet makkelijk aan te passen aan nieuwe wensen. Dat, terwijl ze wel geacht worden vele tientallen en soms honderden jaren mee te gaan. De wensen van de gebruikers veranderen in de loop der tijd. Dat geldt ook voor de omgeving: die kan ook veranderen. Bijvoorbeeld door overstromingen, door intensivering van ruimtegebruik, door milieu-eisen die worden gesteld, door bevolkingsontwikkelingen. Bouwen op water biedt voor al deze tendensen een oplossing. Olthuis liet voorbeelden zien van prachtige kleine en grote woningbouwprojecten op water, van groenvoorzieningen op boorplatforms om flora en fauna te versterken, van stadsuitbreidingen op water. Of een drijvend conferentiecentrum dat van de ene stad naar de andere kan worden gesleept. Het meest aansprekende voorbeeld was misschien wel de woningbouw op de Maladiven. Vloedgolven zijn een grote bedreiging voor de inwoners van deze eilandengroep. De regering heeft zelfs evacuatieplannen klaarliggen voor álle inwoners. Olthuis werkt nu met de regering aan plannen voor drijvende woningen. Uit testen blijkt dat die veel stabieler en veiliger zijn tegen stijging van het waterpeil dan vaste woningen. In Westland waren ook vergevorderde plannen om waterwoningen te bouwen in het gebied tussen Naaldwijk en ’s-Gravenzande. Er was volop belangstelling, vooral voor de goedkopere woningen, maar het project is door de opdrachtgevers geschrapt toen de woningmarkt in heel Nederland inzakte. Hiermee heeft Westland de kans voorbij laten gaan om wereldwijd voortrekker te zijn op het gebied van bouwen op water en een oplossing voor lokale wateroverlast te bieden.

Floating City Apps

Koen Olthuis sloot af met een heel nieuw project: drijvende zeecontainers die gebruikt kunnen worden voor onder andere sanitaire voorzieningen, huisvesting of opleidingscentra voor kinderen uit sloppenwijken. Veel sloppenwijken liggen juist aan water. De wijken zijn overvol bebouwd. Bovendien zijn ze erg kwetsbaar voor overstromingen. De floating city apps zijn metalen zeecontainers met zonnepanelen op het dak. Ze kunnen makkelijk op een eenvoudige drijvende fundering geplaatst worden en zijn daarmee flexibel bruikbaar. In de – airconditioned en hufterproof – containers kunnen ook 20 computers geplaatst die kinderen zelf kunnen bedienen. Zo kunnen ze heel eenvoudig en in hun eigen tempo en in onderwerpen die hen interesseren de wereld ontdekken en zichzelf ontwikkelen. Een leerkracht kijkt op afstand mee en helpt hen waar nodig. Het eerste doel is om – samen met organisaties als Cordaid – in 2017 meer dan duizend floating city apps vanuit Nederland te leasen naar gebieden wereldwijd. De initiatiefnemers zijn op zoek naar partners.

Koen Olthuis at Mosbuild as jury member & speaker

At one of world’s largest building exhibitions, as jury member, Koen Olthuis announced price winners of the MADA award organized by Archiworld.