By Katharine Logan

Architectural record

April.1.2017

As the ice melts and the seas rise, building on waterfront and flood-prone sites begins to look a lot like foolishness, yet backing away from the water takes more willpower than most cities and towns can muster. Ever since the first settlements took root on flood-fertilized riverbanks, next to the water is where people have always wanted to be.

The floating houses designed by Waterstudio, which make up a neighborhood on Amsterdam’s Lake Ijssel, have “foundations” formed in a single pour to eliminate joints.

Photo © Waterstudio

The Waterstudio’s Villa De Hoef, in the Netherlands, normally sits on dry ground alongside a waterway. But when it floods, the house floats.

Photo © Waterstudio

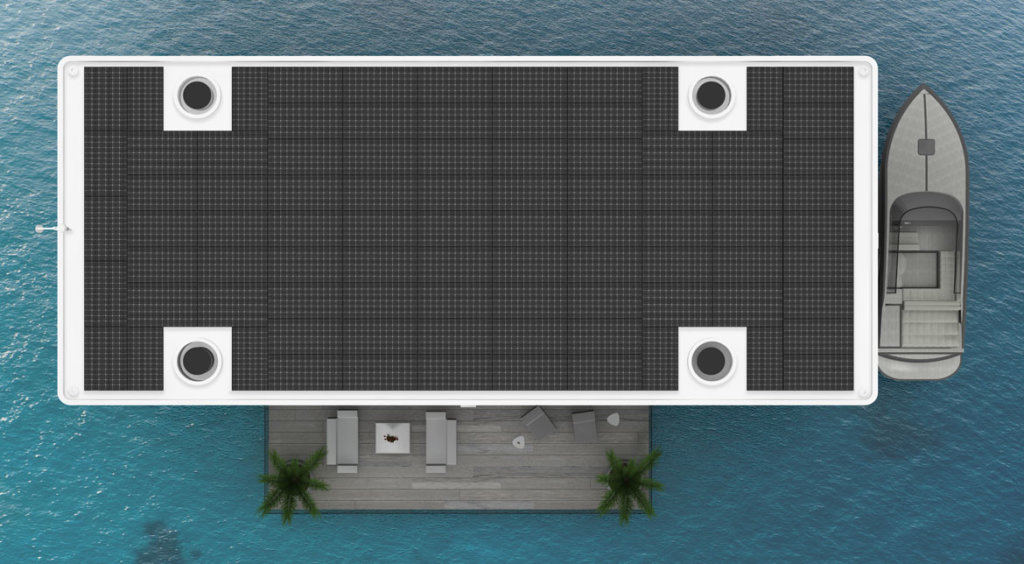

A developer is currently seeking zoning approval to build 29 Waterstudio-designed private floating islands on an inlet north of Miami Beach.

Image © Waterstudio

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Image © Denizen Works

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Image © Denizen Works

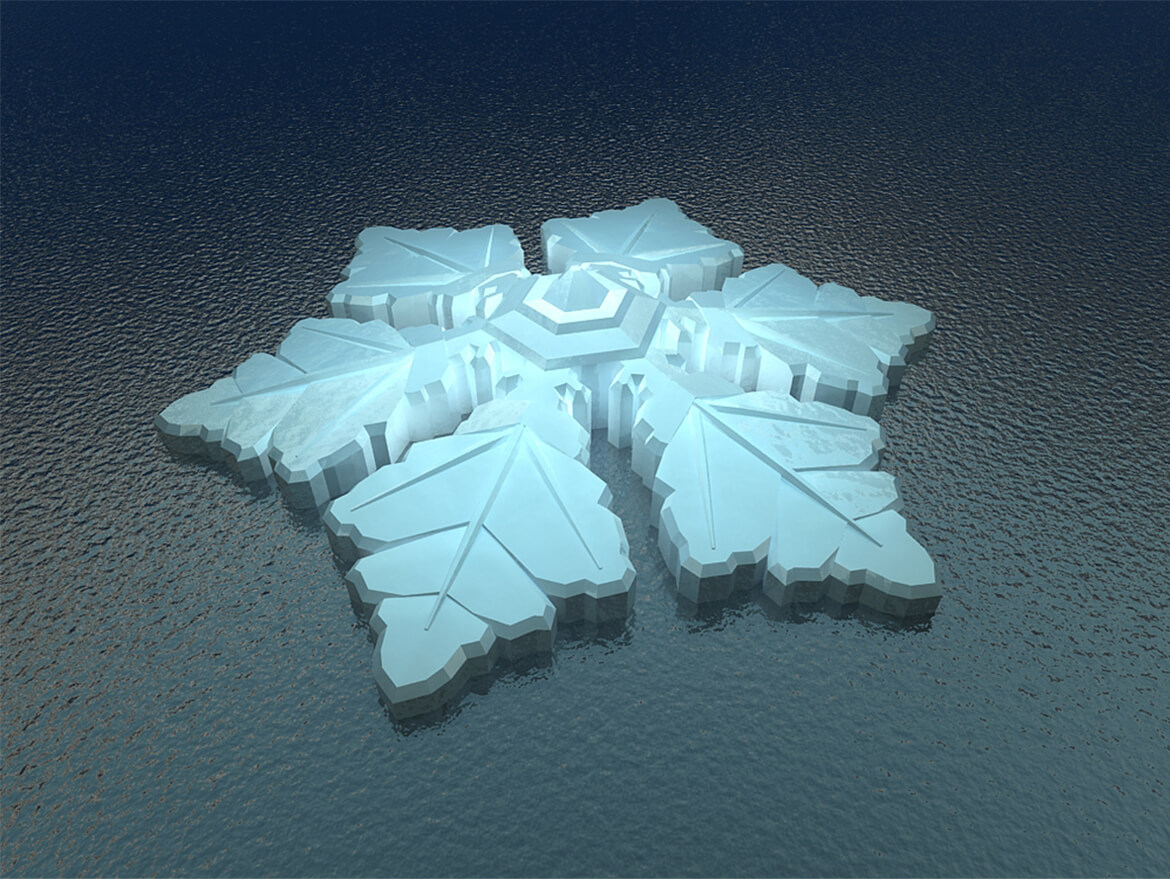

Carlo Ratti’s scheme for Currie Park in West Palm Beach, Florida, consists of interconnected piazzette. The park, which will float on Lake Worth Lagoon, incorporates amenities such as a restaurant, an amphitheater, and a circular pool.

Image © Carlo Ratti Associati

Carlo Ratti’s scheme for Currie Park in West Palm Beach, Florida, consists of interconnected piazzette. The park, which will float on Lake Worth Lagoon, incorporates amenities such as a restaurant, an amphitheater, and a circular pool.

Image © Carlo Ratti Associati

So what are the options for staying put and living with water rather than moving away from it? They range from keeping water out— with barriers, stilts, and raised ground planes —to letting water in, with ground floors designed for periodic inundation, to, ultimately, rising above it all, with floating architecture. Yes, really. “Whether it’s New York or London, Bangkok or Dhaka, all these cities are growing, all these cities are next to the water, and all are threatened by the water,” says Koen Olthuis, founding principal of Netherlandsbased Waterstudio. “Floating developments can be part of the solution.”

The technology of floating architecture isn’t new. Each of the projects considered here uses tried-and-true technology adapted from marine applications to achieve its unusual results, whether it’s a floating house, an island, a church, or a plaza.

Houseboats, for example, have been around for centuries, and the floating houses that make up a neighborhood in Ijburg, under development in Amsterdam’s Lake Ijssel, are “really just better houseboats,” says Olthuis, “built to the same standards as a house on land, using the same methods and materials.”

For all their similarities to houses on terra firma, however, the float houses Olthuis has designed for Ijburg differ in a crucial aspect: their buoyant “foundations,” or lower levels. Formed in a single pour to eliminate joints, and emphatically free of cracks, a prefabricated concrete tub—or hull—is designed to displace a volume of water with a weight equivalent to the weight of the house. The hull is submerged the depth of half a story and secured to telescoping piles at diagonally opposite corners, allowing the house to rise and fall with the water but not wander about. (Typically, bedrooms are located on the partially submerged level, and the water reduces heating and cooling loads on the house.) As a refinement, automatic air-water balancing tanks help keep the house level when the residents invite more than a few friends to a party.

A buoyant foundation can also be used to build amphibious architecture on flood-prone land. Amphibious architecture retains a connection to the ground under ordinary circum- stances and floats as high as needed when flooding occurs. As a flood-mitigation strategy, amphibious architecture works with natural cycles, instead of trying to resist them.

Waterstudio’s 1,440-square-foot Villa De Hoef, for example, usually sits in a garden beside a waterway in the small Dutch town of De Hoef. When the waterway floods, which happens every 10 years or so, the house floats; as the flood recedes, the house returns to its original position. With a maximum anticipated flood level for the site of only 4 feet, the project’s engineers deemed it safe to tether the house with cables and surround it with a wooden deck, in preference to telescoping piles. A skirt of nylon net prevents flood debris from becoming lodged beneath the house. “Low-tech, low-maintenance,” says Olthuis. Maintaining the amphibious system requires periodic visual inspection of the cables and deck, and, every five years, a recalculation of the house’s added or moved live load to determine and adjust its center of gravity. This is in case the occupants have accumulated more belongings or rearranged the furniture.

Expanding the applications for floating architecture, Waterstudio is now designing private islands that will float on a patented platform moored to the seabed. With projects under way for Dubai and the Maldives, the firm’s Amillarah project is currently seeking zoning approval for a “villa flotilla,” as the Miami Herald dubbed the proposal, with 29 floating islands on Maule Lake, an inlet north of Miami Beach.

Expected to sell for about $12.5 million each, the floating islands will make only a few hundred very wealthy people happy, notes Olthuis. Ultimately, however, he sees a more egalitarian future for the technology, as a solution for people worldwide who live in slums that are close to open water and vulnerable to flooding. Improving these so-called wet slums is almost impossible, since governments are unwilling to condone illegal settlements by sponsoring upgrades and because lenders are unwilling to invest in something that will be flooded out.

But, building on their experience developing floating islands, Waterstudio has proposed simple schools and critical infrastructure, such as water-treatment plants, that would sit on small floating islands and be connected to the slums. The firm has recently completed a prefabricated floating school that will be shipped to Dhaka and assembled next to a wet slum there. Such facilities typically qualify as temporary solutions, which makes them acceptable to government officials. They can be relocated as needed, retaining their value, which makes them attractive to investors. And they can be leased for limited periods, which makes them accessible to the communities that need them. “It’s a delicate system, where you get investors, regulators, and users all together to improve life in these wet slums,” says Olthuis.

A versatile, affordable, and mobile solution is exactly what the Church of England’s Diocese of London was looking for when it commissioned London-based Denizen Works to design a floating church and community hub to support the diocese’s outreach program along London’s waterways.

With the rocketing cost of land, London’s waterways are the busiest they’ve been since the industrial revolution, with a floating bookshop, cinema, restaurants, and even a puppet theater, as well as a significant residential component. The activity on the water could soon be eclipsed, however, by the activity of new development along the water’s edge. In 2015, the mayor’s London Plan identified key brownfield “Opportunity Areas,” many of which lie along these waterways.

With its floating church, the diocese is responding both to the anticipated growth of new waterfront communities on brownfields and underdeveloped lands, and to the difficulty of finding space in the rapidly redeveloping city for a new church. “We spotted this opportunity,” says Hayley Harding, program management officer with the diocese, “and felt that it was something that could grow and support development and change.”

The priority for the diocese is to establish a presence in emerging communities—on and beside the water—as early as possible, and in a space that the local parish can own and manage, running both secular and worship activities as it sees fit. The floating church will moor at key regeneration sites for threeto five-year periods, offering services, and developing relationships with growing communities. Ultimately the Diocese will evaluate whether and how to build a permanent facility.

The competition brief for the project called for a multifunctional space that could accommodate a diverse program of worship and celebrations, art exhibitions, yoga classes, parent-and-toddler groups, and supper clubs. “They’re not just looking to bring the church to these emerging communities,” says Murray Kerr, director at Denizen Works, “but a sense of community as well.”

Denizen’s winning scheme, developed in collaboration with Turks Shipyard and based on a traditional wide beam canal boat, provides 500 square feet of interior space, plus decks, in a vessel that is 60 feet long and 12 feet wide but less than 6 feet above the waterline, so that it can easily clear the London canal system’s low bridges. The design, which is projected to cost about $370,000, includes an innovative roof that generates a play of light and volume. Once the vessel is docked, the roof’s two asymmetrical segments can be raised to reveal pleated sides much like the bellows of a church organ (or, more prosaically, the pop-top of a vintage camper). The longer wing shelters the hall, while the shorter one covers the ancillary spaces, including a kitchen and an office. Crafted from resinimpregnated sailcloth, the translucent bellows will provide a soft, ambient light during the day and act as a Chinese lantern at night, says Kerr, “creating a warm, inviting glow for passersby and imbuing the interiors with a celestial quality.”

“They delivered something we weren’t expecting,” says Harding. “This beautiful volume is something that can be a sacred space as well as a community asset. And Denizen’s partnership with a shipyard demonstrates that it is viable.”

The church will be Denizen’s first project to float. By contrast, the work of Turin, Italy– based Carlo Ratti Associati demonstrates an abiding fascination with water, so it’s no surprise that the firm’s 2016 master plan for the Currie Park waterfront at West Palm Beach, Florida, incorporates a significant water-based element. What is unexpected is the use of a technology adapted from submarines to carve volumes of habitable space into the surface of the Lake Worth Lagoon.

“One of the aims of our work is to imagine an architecture that adapts to human need, rather than the other way around—a living, tailored space that is molded to its inhabitants’ needs, characters, and desires,” says Carlo Ratti, the firm’s founding partner and the director of the Senseable City Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Water is a reconfigurable material, and it allows us to develop adaptive, ‘fluid’ designs.”

The plan envisions a floating plaza (or, perhaps more accurately, a series of floating piazzette) projecting out onto the lagoon. The plaza will hang in the water, with its surface about 5 feet below sea level, providing views across the water from this unusual perspective. The project is anticipated to have virtually no environmental impact, floating in the lagoon just like a midsize boat, using no fuel, and discharging nothing into the water.

As part of the 50-acre master plan, the plaza will connect to West Palm Beach’s city center along a pair of leafy promenades, and will incorporate such facilities as an organic restaurant with its own hydroponic cultivations, a circular pool, and an amphitheater.

Now in design development while seeking municipal approvals, the plaza will consist of a series of lightweight steel modules composing a peninsula of about 5,000 square feet. The structure’s deck will be made of galvanized steel (similar to boat construction), with teak finishes. Beneath the plaza, a series of sensoractivated air-water chambers will open and close, releasing or taking in water according to the number of people walking on the surface, and adjusting for a height differential of up to 20 inches, which accommodates loading changes of up to 100 pounds per square foot. “The use of responsive digital technologies is often employed to introduce movement and complexity to static architecture,” says Ratti, “but it can equally be used to achieve stasis and equilibrium within a moving landscape.”

With this project, West Palm Beach aims to reclaim its connection to the natural environment it is part of, give shape to a vibrant new district, and, says Ratti, “radically redefine the relationship between architecture and water.” Ratti has identified the theme that unites these disparate examples of floating architecture: a floating plaza that engages with water in a playful new way; a floating church that enables an ancient institution to reach out to its changing city; floating islands that uplift the few and the many; amphibious architecture that celebrates a river even in flood; and a floating neighborhood that provides a city with new “ground.” All of these offer new possibilities for changing waterfronts and new possibilities for us to stay where we really want to be—by the water.

Click here for the full article in pdf

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.

Denizen Work’s proposal for a floating and relocatable church for the Diocese of London features a roof composed of a pair of asymmetrical, pleated wings. These are lifted, like the pop-top of a vintage camper, once the vessel is docked.