Quartz, Siraj Datoo, Aug 2013

Dutch architect Koen Olthuis specializes in building things that float. His structures, he concedes, use a similar technology to oil rigs. Yet Olthuis’s focus is elsewhere—on combating rising sea levels, floods, and a growing world population. As he outlined in a TEDx Warwick talk last year, the work he’s doing is quite literally putting land where there wasn’t any before.

Olthuis is the founder of architectural firm Waterstudio.NL, and as a native Dutchman, he often cites his own country’s history as inspiration. “In Holland, we have always been fighting against the water… 50% is under sea level,” he said in his talk. Yet he finds this ongoing battle with water “strange”, arguing that it makes the country susceptible to danger. “What if something breaks?” he said in a phone call with Quartz. His solution: “Why don’t we just use the water?”

His projects include designing homes in Holland, schools in slum neighborhoods in Bangladesh, “amphibious houses” in Colombia, a star-shaped conference center, and a 32-island golf course (with, yes, underwater glass tunnels linking the islands) in the Maldives. He’s also looking to sign a contract to design villas in Florida.

How does it work?

There are three main elements here. The floating base:

[It] is the same technology as we use in Holland. It’s made up of concrete caisson, boxes, a shoebox of concrete. We fill them with styrofoam. So you get unsinkable floating foundations.

And the bit on top?

The house itself is the same as a normal house, the same material. Then you want to figure out how to get water and electricity and remove sewage and use the same technology as cruise ships.

How it is anchored to the ground?

In Dubai, they just put sand into the water and made artificial islands. Once you put sand into the water, you can’t go back. We can go back after 150 years and there’s no damage to the habitat.

That’s impressive. So what do you do exactly?

[In the Maldives], these houses are connected to a floating boulevard… Those are connected to the sea bed with telescopic piles and as the boulevard rises up from sea level and the house rises up.

And all that means that if there’s a rise in the sea level, due to a flood or tsunami, the island will just rise?

Yes.

“We don’t believe in donating money,” he tells me. “It didn’t work in the history [sic] and it won’t work in the future.” When you give money to charity, he argues, you rarely know what impact it has had.

His response to this is the City Apps Foundation. Instead of donating money for food and aid, companies provide financing for “apps”—interchangeable, prefabricated units such as classrooms, social housing, first-aid stations, or even parking lots. Like the apps on a smartphone, they’re designed to be easy to install and launch with the minimum of fuss. After an initial free trial, schools, governments and local municipalities can lease specific “apps” for a monthly fee. The fees yield a return for the investors, and when the apps are no longer needed they can simply be packed away and assembled in another city. The foundation has raised funding from a number of Dutch companies, and Olthuis and his company provide the technology.

The foundation’s first major project is a school in a slum in Dhaka. Olthuis says that slums have specific problems that appeal to him—in particular their instability. At any moment “the government can say that we’ll take the slums out or landlords might kick them out,” so slum-dwellers tend not to invest in their communities.

City Apps gives power to these neighborhoods, Olthuis argues, especially because they are often situated on the edge of water. In Dhaka, the school app will be a white container that stands out from the rest of the slum to create what Olthuis, perhaps inadvisedly, calls a “shock and awe effect”. The schools will contain iPads for use by the students, and women will use the space for evening classes. Within 12 weeks, the schools will have been built, transported to Dhaka, assembled and ready to use. If the community is forced to move, the school can move too with relative ease.

Olthuis says there are two ways that the City Apps foundation is a better system for investors:

It provides accountability. Cameras inside the containers will allow investors in the project to show off the fruits of their social spending to clients or shareholders in real time.

Although the initial school app will be free, slum-dwellers will have to pay to lease extra apps, such as what Olthuis calls “functions” for sanitation (this could be anything from a toilet to a fully-fledged bathroom) — or even just the ability to print. If the slum no longer wants a specific “function”, it can be easily taken away and used elsewhere. Investors get money if more “apps” are leased

“[It’s] stupid that each [sic] four years, we build complete neighborhoods and then they leave it there.” And it kind of is. The British government spent almost £2 billion ($3.1 billion) on venues alone for the Olympics and Paralympics village for London’s 2012 games. Instead, Olthuis suggests, Olympic cities should lease floating stadiums and property. This could be assembled in advance of the games and packed away afterwards, and would be far cheaper than creating new stadiums and neighborhoods every four years. While it would certainly remove some of the sparkle around the event, it would cut a good deal of waste. In Britain, talk of how the OIympic venues could be used after the games has already faded away.

Work on the “ocean flower”, part of a project that will see 185 new floating villas, has already begun and the first villa will be inhabitable as soon as December this year. Americans, Chinese, Russians and even hotel operators have already forked out the $1 million cost per villa.

Olthuis has a contract with for 42 amillarah islands (private villas in the Maldivian language). These will be 2,500 sq. meters (26,910 sq. feet), and, at $12 million-$14 million, for the “stupidly rich”, Olthuis lets slip.

You can take a speedboat-taxi from the airport in 15 minutes or a three-person “U-boat” submarine will get you there in 40. (Russian president Vladimir Putin was seen modelling the five-person version.) Alternatively, spend three weeks learning how to maneuver a U-boat and a license is yours.

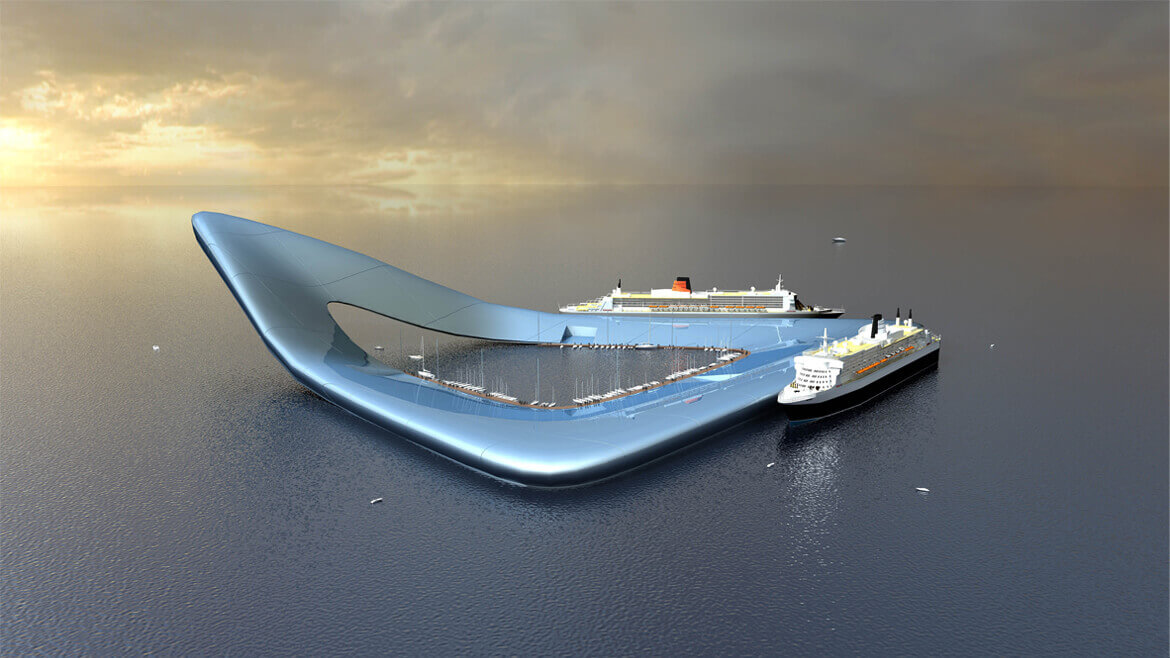

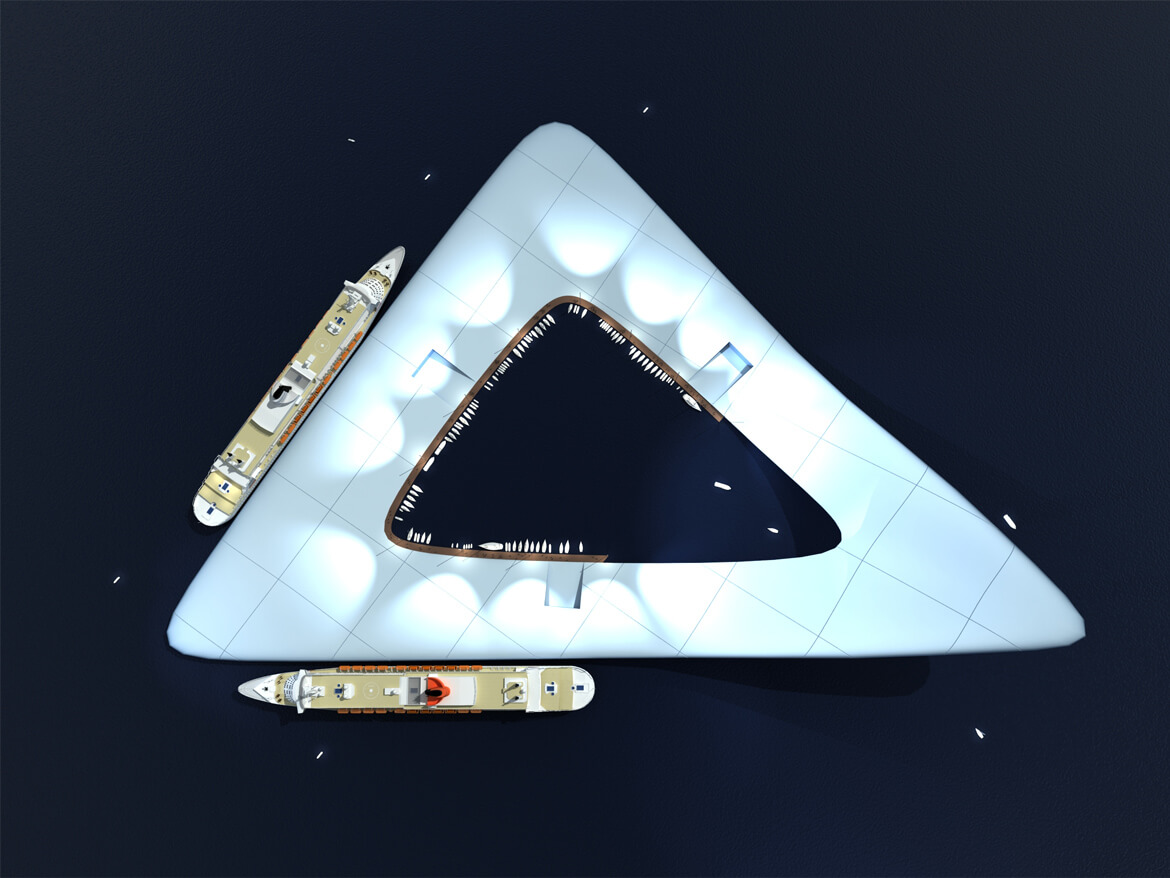

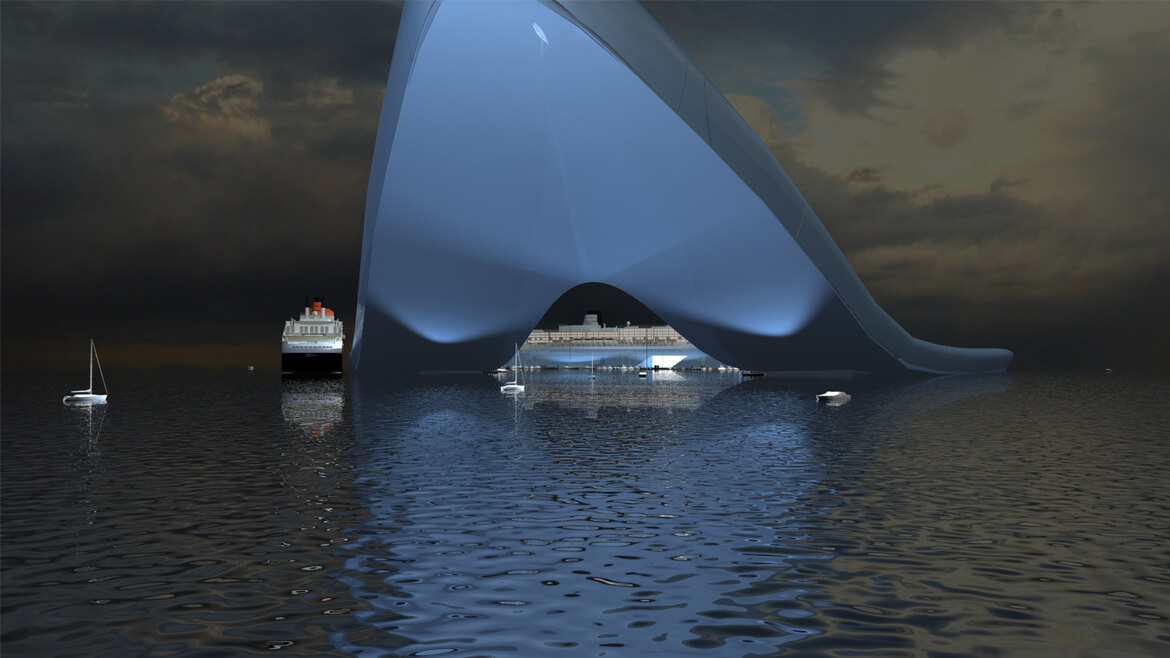

What if there was a hotel-cum-conference center in the middle of the ocean? Construction on this complex will begin towards the beginning of 2014 and with it come some interesting innovations. While a starfish has five “legs”, Olthuis’s company will build six. This means that if a section needs to be renovated, they could replace one leg with the spare (kept at the harbor) within three days instead of having to cordon off the area for months.

In his TEDx Warwick talk, Olthuis jokes that even if you’re on honeymoon in the Maldives, after a few days of glorious swimming, you kind of just want to play golf. And while the golf course might not be swarming with newly-weds, it might attract a new set of tourists from Russia and China.

Even if you’re not much of a golfer, it’s likely you’ll make a trip just to walk in the underground tunnels between the islands. And yes, the tunnel will be transparent.

Colombia has three big flood zones and every time there’s a flood, local municipalities have to pay a lot of money in compensation, according to Olthuis. To combat this, the local government has signed up Waterstudio.NL to build 1500 “amphibian” houses with a floating foundation.

So while the above photo depicts a floating house in a dry season, the house will simply rise in a wet season. While it’s a fairly simple concept, it has radical implications.

Olthuis’s biggest impact so far has been in Holland, where a number of water villas have already been completed. With over 50% of the country below sea level, this provided the perfect playground for his concepts to become a reality

Click here to read the article

Click here for the website

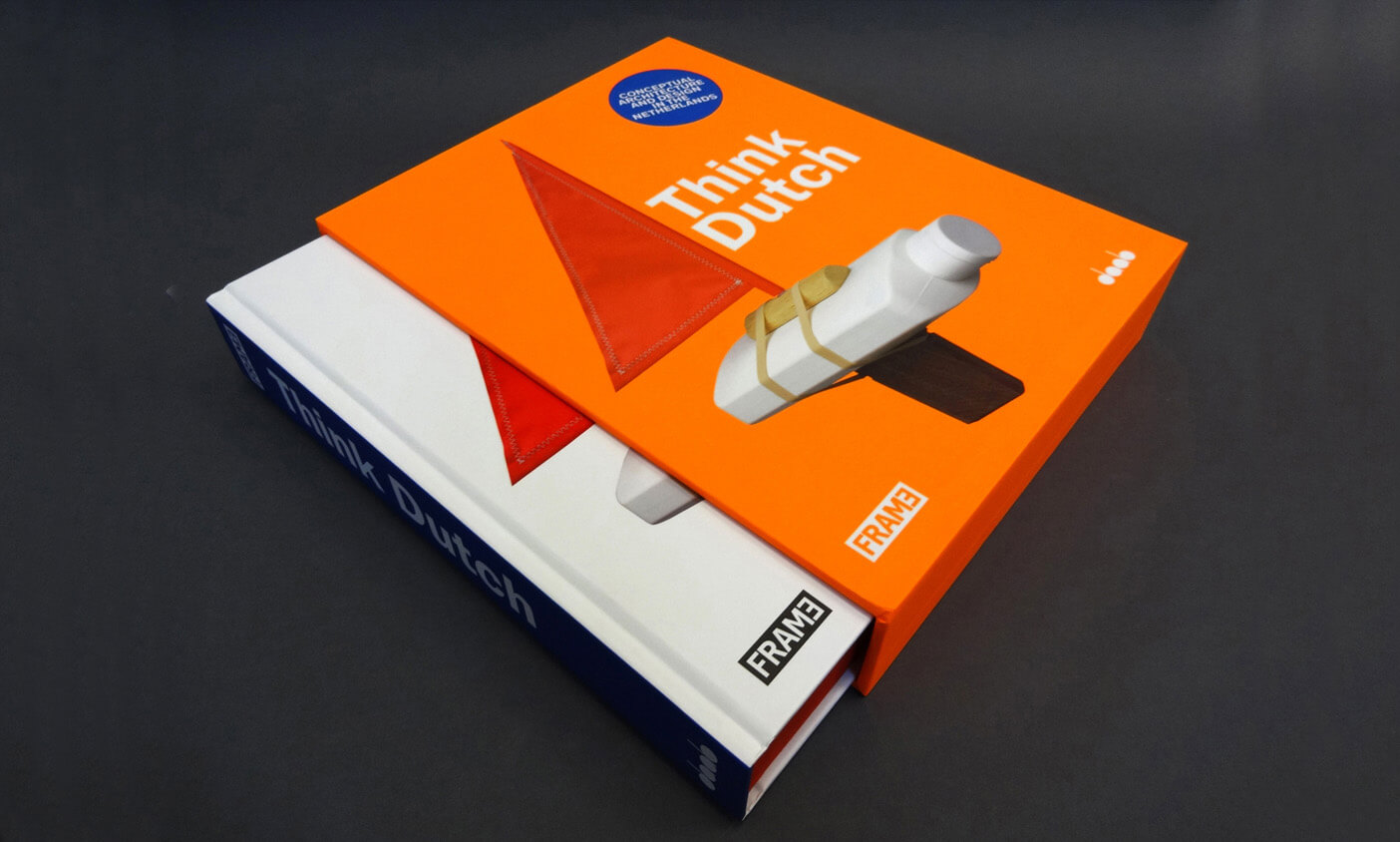

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS