Inhabitat, Bridgette Meinhold, July 2014

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Despite his busy travel schedule, Olthuis had a chance to answer our questions with a great amount of detail and thought. Not only is Olthuis a leader in designing floating architecture, he’s the most-interviewed architect on Inhabitat. We think very highly of his work and ideas, and we think you’ll agree after reading through his thoughtful answers about the pressing issue of climate change. Don’t worry, it’s not all gloom and doom though—Olthuis proposes a future full of hope and promise!

Inhabitat: What does climate change mean for cities on the coast, and how serious is a sea level rise of 1 meter?

Koen: I think that climate change is a serious problem for these cities because most of them have been built upon the wrong parameters. For centuries, sea levels and climate have been relatively stable, which has brought us urban plans and built environments that are too static—like a one-trick pony for one certain set of conditions. With the arrival of uncertainty in , we have to rethink our coastal cities.

The threat that climate change brings is not just the physical threat of floods and drowning, but also the financial impact of destroyed property and businesses. Through the last century, waterfront development has increased in value as well as assets. Flood threats will put pressure on available dry space and reset the parameters for which parts of a city are desirable, and which are dangerous.

The effect of a one-meter sea level rise (without any adjustment to coastal cities as they stand today) would completely reset maps and financial stability in many of the world’s biggest waterfronts. New York, Miami, and Guangzhou would lose an important part of their real estate to the water. Countries like Bangladesh and the Philippines would have to give up lots of land. In the Netherlands, many of the water defense systems that protect the country under sea level will no longer be safe.

The question of how serious a one-meter sea level rise would be cannot be answered without placing this question in a certain timeframe. Although cities may appear static, they’re in constant change. The lifespan of urban components like infrastructure, normal buildings, and water defense measurements isn’t more than 50-100 years. This means that if the change occurs within the next 50-100 years, cities have time to grow into components designed upon the new parameters. If the rise occurs faster, cities won’t have time to adapt naturally and problems will occur. The problem is that because sea level rise is quite slow, governments find it hard to deal with a long timeframe when short-term strategies will lead to immediate benefits.

Inhabitat: What do coastal cities need to be thinking about and planning for in order to prepare for the inundation of water?

Koen: First, they have to design plans with flexibility—not solely for today’s conditions. Second, they might be better off embracing the water instead of fighting it, seeing urban water as a chance to upgrade our cities rather than a side effect.

I think that a resilient city isn’t one that prepares for the water to come, but one that allows it to expand. By letting in water and making it part of the city, rising levels or storm conditions will only mean working with a bit more water instead of the big shock that comes when conditions go from dry to flooded.

Regarding planning, coastal cities should focus on which areas should be kept absolutely dry, which can be changed from dry to wet, and which existing waters can be used for expansion. The future of resilient coastal cities is on the water, and metropolises like London, Miami, Tokyo, and Jakarta will expand their territory by 5 to 10 percent on urban waters in the next 25 years.

Inhabitat: Can you give us examples of any cities making promising strides to become more resilient?

Koen: Many are slowly taking defensive measures to become more resilient, but there is one that seems to use a highly innovative path: Jakarta. This capital of 10 million is suffering not only from climate change, but also from urbanization. The soil is sinking at a speed of 15 centimeters per year, which raises flood risks and effects, and it’s getting polluted with saltwater, which has a huge effect on fresh water reserves. Instead of building only higher water defense systems like dikes, which wouldn’t solve the saltwater problem, they’ve chosen to embrace more innovative solutions provided by Dutch engineers and urban planners. The solution focuses on closing Jakarta bay with a dike, turning it into one big 100 km2 wet polder; a size needed to provide enough storage area for extreme weather conditions.

On this dam, a city of a million people will be built facing the old waterfront of Jakarta on one side and the ocean on the other. For architects focusing on floating architecture, this kind of artificial large-scale wet polder provides a big opportunity: in order to keep the storage as big as 100 km2 you cannot build in the water, but floating structures have no effect on storage capacity. Jakarta can become one of the most resilient coastal cities of Asia and still make money from these measures—fighting water with water by adding the storage polder.

Inhabitat: If you were put in charge of making, say New York City, resilient to flooding and climate change, what strategies would you implement?

Koen: New York is one of the most iconic cities in the world, and Manhattan is the benchmark for high-density urban developments, but this city has also evolved to accommodate the surge for space. The enormous land expansion over the river beginning in the 17th century provided the city with new space. The elevator facilitated building into the air, and the metro system took advantage of space beneath the city. Without any of these innovations, Manhattan would look completely different. The lesson here is that standing still doesn’t always benefit cities, and innovations (daunting though they may appear) can bring new prosperity.

The biggest problem that New York will have to face isn’t a steady one-meter sea level rise—because that can be overcome with a meter-high levee—but the effects of extreme weather. Storm conditions like Hurricane Sandy will raise water a few meters and yield heavy rainfall that cannot be transported to the river, since the river itself will rise to record levels. To keep the subway system dry in normal conditions, huge amounts of water have to be pumped out; any additional water could make the system flood.

New Yorkers haven’t embraced the waterfront as much other coastal cities. The view inside is more important than outside and the most valuable real estate can be found around Central Park. [There are] no nice boulevards like in the south of France; nice beaches or green habitats can be found at their manmade border between land and water.

Having said this, I would bring the strategy of fighting water with water to New York and start wetting up the city. If we raise the level of the water ourselves by a few meters, it won’t be any problem when nature does it. To raise the level of the river and still use it as such is impossible, but there’s another Dutch solution that could work. In Holland, existing polders are surrounded by artificial canals. The water in these canals is a few meters higher than the polder waters. They aren’t dug into the landscape, but put on top of the landscape with a dike on both sides to keep the water in. Water from the polder is pumped into the canal and then transported to the rivers or the sea. The canals can be artificially controlled, providing a kind of buffer, and can also be used for transport, and waterside houses. I’d like to create a necklace of small, connected artificial lakes around Manhattan; a system much like an extra canal with a higher water level than the surrounding rivers. This canal would be divided into sections that could be closed separately.

This new zone will take the place of the existing harbor quay—the river width wouldn’t be affected, but the result would be like a set of airbags around the city. In case of high tide, these cells would serve as storage polders that could release water when the storm had passed. These cells would change the edge of Manhattan: the water cells would look like small lakes, and new settlements could be built on the levees dividing them from the river. These lakes would all be connected, and they’d only be closed off from each other during storm conditions, like compartments in large cruise ships.

The artificial lakes would fill the space now used by the river docks, and have a flexible water level that would provide an enormous storage zone, providing safety encroaching seawater. As I imagine, there would be as many as 40-50 of these lakes, each as long as 4-6 blocks. Lakes for leisure, for green floating communities, lakes with harbors—the greener the better.

Inhabitat: With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati losing their land to rising sea levels, how do they respond and provide for their citizens? Buy property elsewhere or construct floating cities? Are there estimates on how much it would cost to construct floating countries?

Koen: The Maldives and Kiribati are both series of small islands in the middle of the ocean, which will be highly affected by any sea level rise. Without enough dry land available, these countries have to make the choice to become climate refugees or adopt floating technologies and become climate innovators.

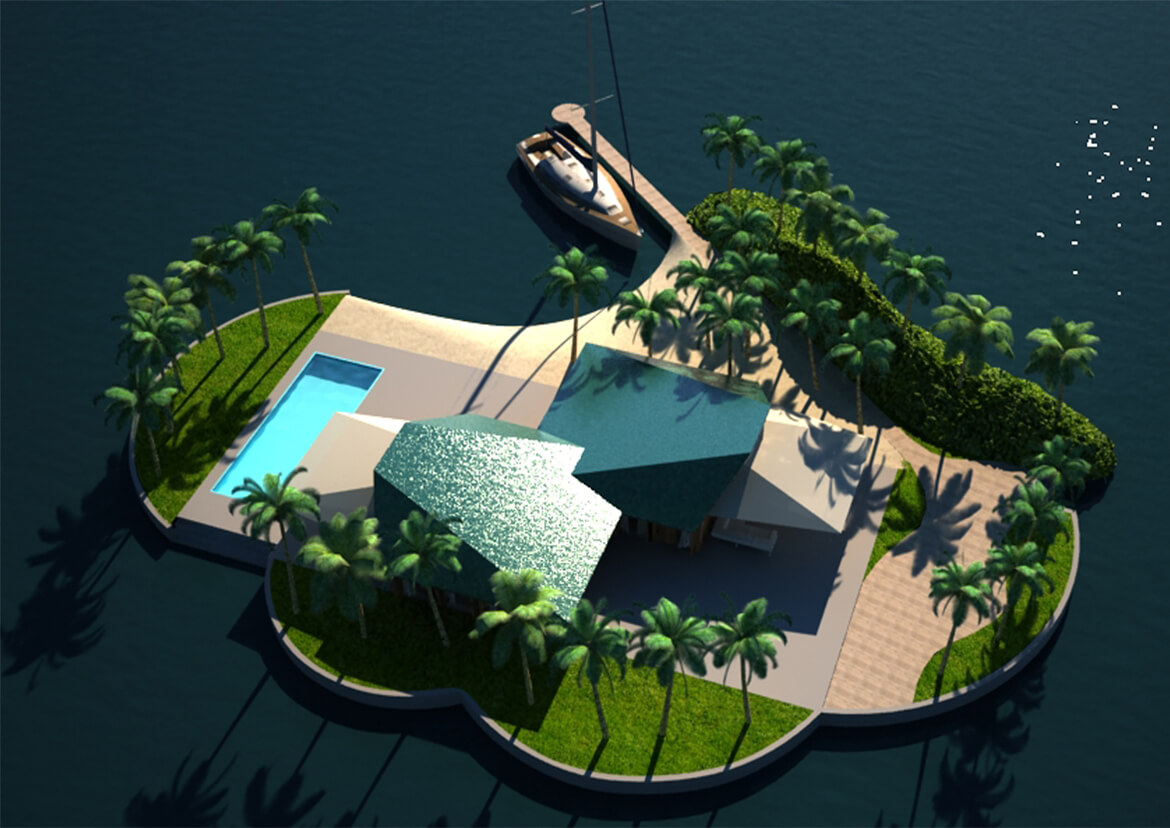

In the Maldives, Waterstudio has designed floating island resorts and a golf course for developer Dutch Docklands. They are building a joint venture with the government of the Maldives, both as a tool to increase new possibilities for tourism, and to reinforce society with long-term floating developments. Floating islands with high-density affordable housing could be added to the existing islands to provide space and safety. Floating developments are scar-less and mustn’t have any impact on marine environment during or after their lifespan.

This could lead to floating countries, keeping in mind that the Maldives has 300,000 inhabitants. The cost of these floating islands is comparable with dredging islands, only that dredging destroys sea life and coral reefs. If I must make a reasonable guess I would say around $25,000 per person, so for a city of 20,000 people it would cost 500 million dollars. This might sound like a lot, but it’s quite reasonable compared to evacuating a nation.

Inhabitat: How has your work changed over the years in response to the pressing needs of climate change?

Koen: The possibility of improving coastal cities worldwide with the implementation of floating urban components is just so challenging. It feels like we have only just discovered a small part of the potential that water could bring in making cities more resilient, safe, and flexible. I believe that projects like these will set new benchmarks for cities that would otherwise be in trouble because of climate change.

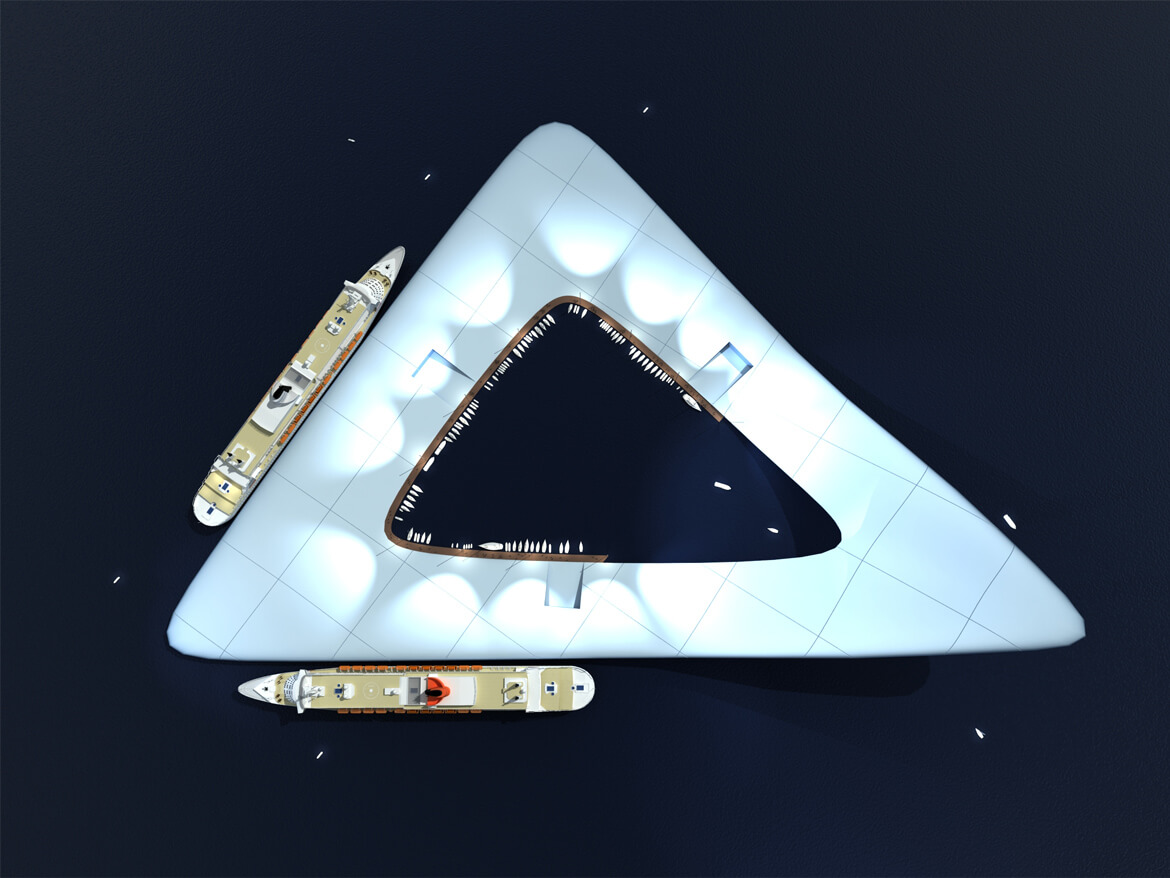

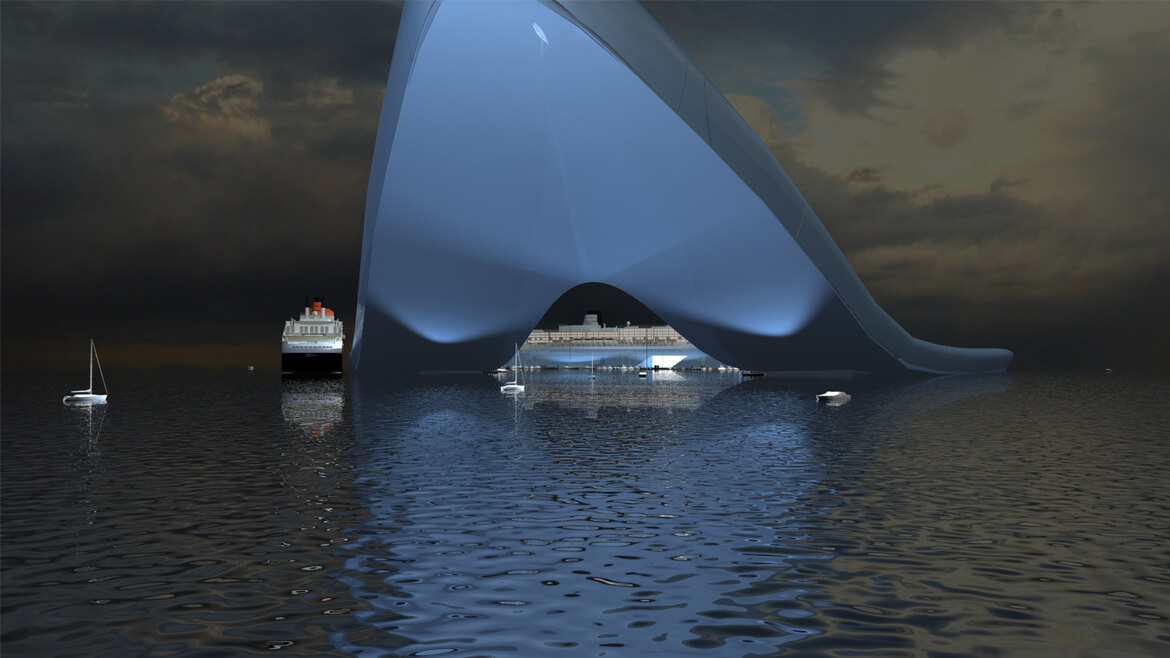

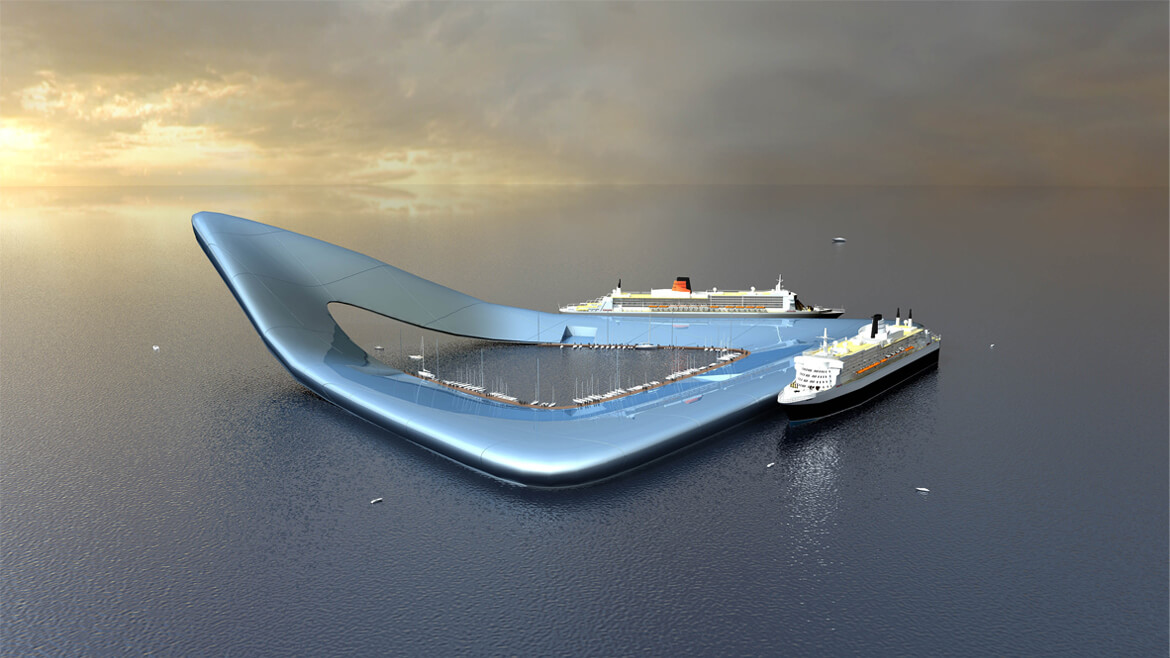

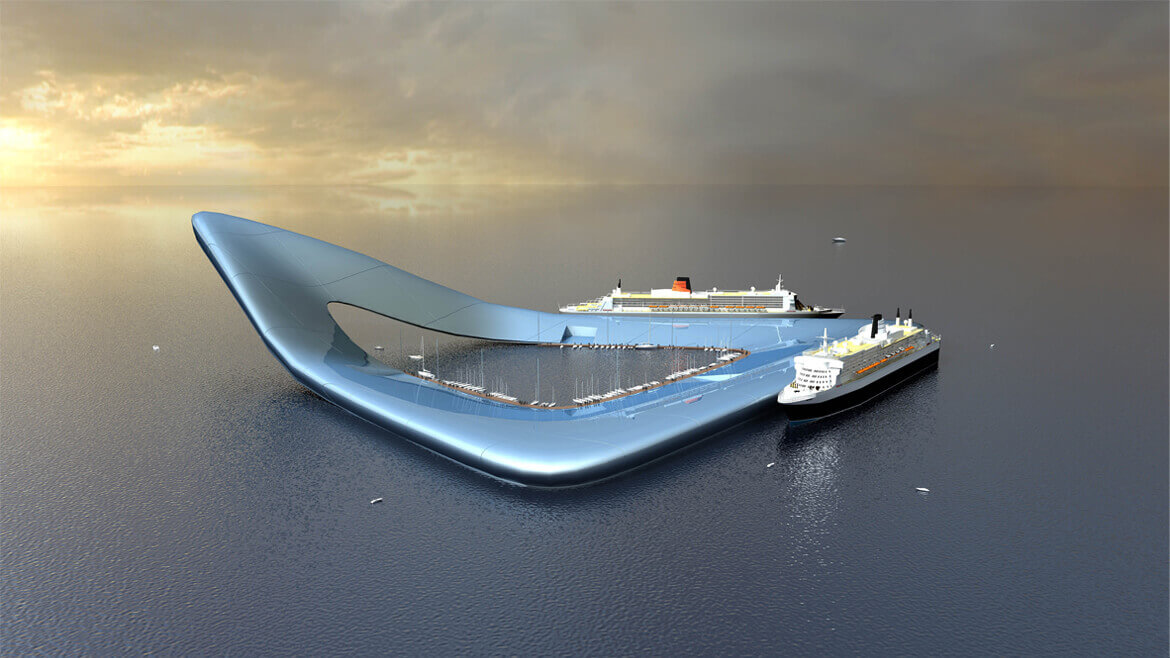

Our research seeks to change perception and dogmatic rules that traditional planners from the static era have put on us. I think that just in the last two years, iconic designs like the floating cruise terminal have developed an extra dimension—they’re part of a bigger vision that looks beyond iconic architecture to the economical impact it could bring.

My work has gone from designing for rich individuals to designing for the poor. We now design strategies for cities that have to adjust their planning approach because of shifting conditions due to climate change. The focus on slums has opened a whole new window of opportunity and has brought me in contact with many people who believe architects must use their influence and creativity to make a change for millions instead of only the happy few.

Inhabitat: Tell us briefly about your latest project, City Apps, and how it can help cities deal with climate change.

Koen: Miami and New York are the cities most threatened by sea level rise in terms of exposed real estate, but the populations most threatened by sea level rise would be in Mumbai, Dhaka, and Calcutta. In these cities, millions live in dense slums close to water. In fact, one billion people worldwide are living in slums, and half of them can be classified as wet slums because of their relation to the water. People living in these areas are terribly vulnerable to flood danger. Efforts to help these cities should not focus on protecting the built environment, but on protecting essential functions during and immediately after floods. Slums can be helped by upgrading programs to improve life conditions for 100 million people before 2020, as stated in the 2003 UN habitat millennium goal.

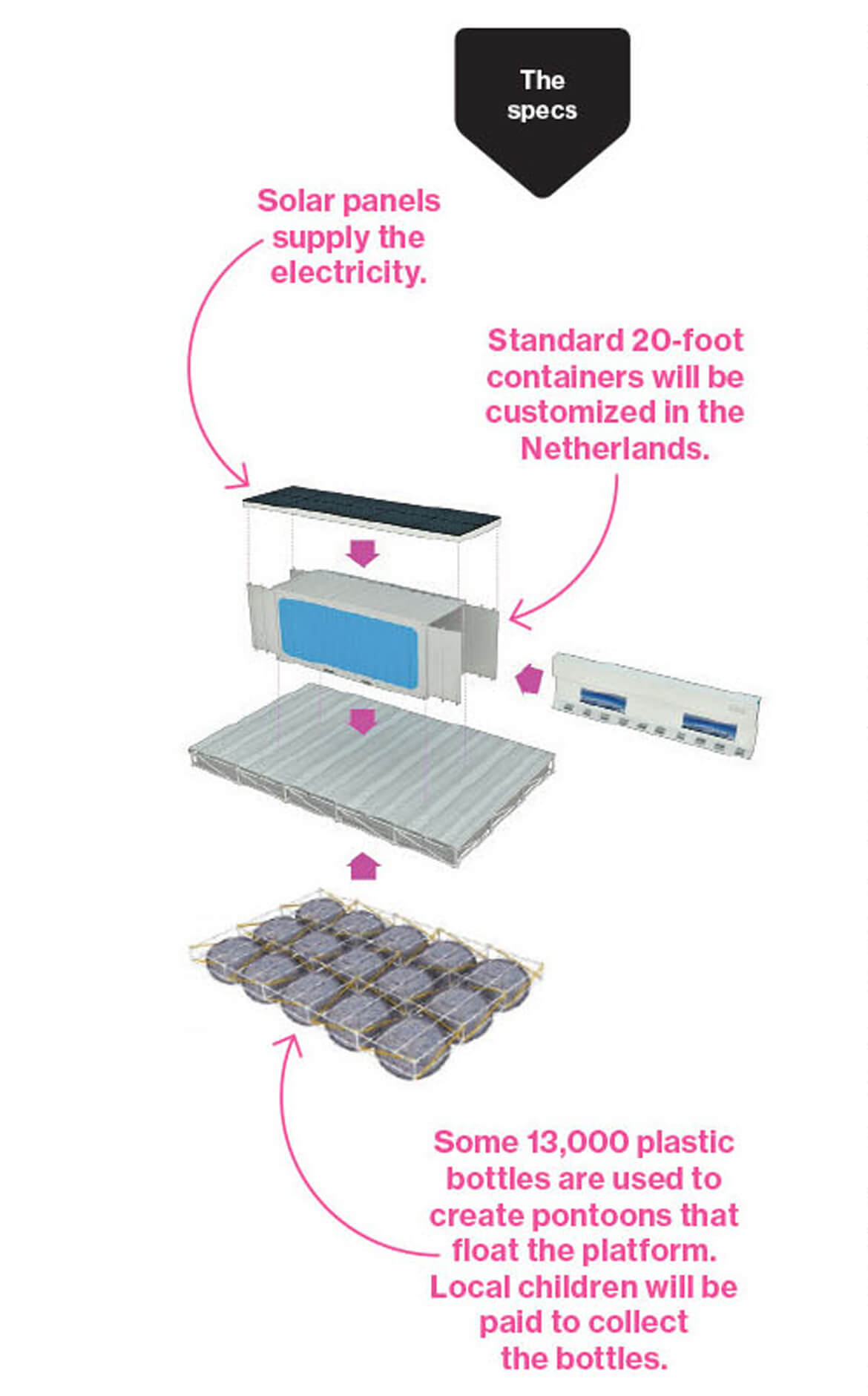

Programs in wet slums are not generally upgraded, because investing in them is a risky business, as floods could potentially destroy any functions built in areas close to the water. We want to use our technical knowledge to provide floating functions on water for these wet slums.

Just as you can download apps on your smartphone according to your changing needs, you can adjust functionality in a slum by adding functions with City Apps. These are floating developments based on standard sea-freight containers, and because of their flexibility and small size, they are suitable for installing and upgrading sanitation, housing, and communication.

Inhabitat: What advances in technology, design, or materials have helped push your architecture forward?

Koen: In Holland, we have always been close to maritime technology. It is very exciting to take these technologies that are meant for things like offshore oil industries and use them to create a floating habitat for animals, birds and underwater creatures like the Sea Tree does.

I think the Internet and 3D visualization tools have really pushed my architecture forward because in an industry as young as floating architecture, it is only the power of visualization that can show the impact of floating developments for the city of tomorrow. The fact that we can spread our ideas around the world and get feedback, response, and help because of the digital revolution is unbelievable. If I would have started twenty years ago I probably wouldn’t have reached more than half of Holland, and Holland isn’t that big.

My designs are what we call “readable architecture”—product-like solutions that ask for simple and clear details. Not every material is suitable for that, and over the last three years we discovered sustainable composites that suit the architectural expression I want, and are ideal for projects in salty environments that require low maintenance.

But the most important advantage in technology is logistics. The fact that we now can produce our floating houses and developments in different countries and assemble them on the water without affecting the environment makes it possible for us to rethink economical models for large-scale production.

Inhabitat: What are you most excited about right now in this field?

Koen: I am most excited about how global mobile assets will enable cities in developing countries to leapfrog to higher prosperity. These assets are large-scale floating developments that are being invested in by very rich countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or Norway. These countries have so much money to invest that they cannot spend it all in their own country. Instead of investing only in wealthy world capitals, they’ll invest in flexible real estate, which can be leased to coastal cities.

It’ll start with functions like floating hotels and stadiums for cities that want to organize the Olympic Games but who cannot afford the investment. But it will rapidly evolve into an industry where cities that have been hit by climate change-related disasters can lease an entire set of functions like energy plants, hospitals, schools, and sanitation. Just like we do with our Floating City Apps for wet slums, there will be large-scale solutions to instantly upgrade cities and help communities recover. I see floating harbors and even small floating airports that’ll provide instant infrastructure to cities recovering from natural disasters.

The enormous financial capacity of these countries enables them to build global mobile assets up front on stock. So, imagine a safe floating location somewhere in Asia composed of completely functional urban components ready to be towed to any disaster area that appears. All the technology and money is already available—it’s only a matter of changing perception before floating developments are an essential part of the climate change reality that’s waiting for us. I say that not as a negative sentiment, because I believe that change will lead to innovation that will bring prosperity. The future is wet, the future is good!

Click here for the website

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.

La compañía, con sedes en Amsterdam, Dubái y Maldivas, confirma vía correo electrónico que ya se ha iniciado la construcción de la primera fase: “Se llama La Flor del Océano y consiste en 185 impresionantes casas sobre el mar, conectadas por un embarcadero, formando esta flor, que es el símbolo nacional de las Maldivas”, explica Klaas Boon, uno de sus responsables. Añade que las viviendas están a la venta “bajo la exclusiva etiqueta de Christie’s International Real Estate” y que los precios se sitúan “sobre el millón de dólares por villa”.