Dutch solution to Miami’s rising seas? Floating islands

By Jenny Staletovich

Miami Herald

August.23.2014

Maule Lake has been many things over the years: industrial rock pit, aquatic racetrack, American Riviera. Now it is being pitched as something else entirely: a glitzy solution to South Florida’s rising seas.

In the land of boom and bust where no real estate proposition seems too outlandish — Opa-locka’s Ali Baba Boulevard connects to Aladdin Street in one of the more kitschy bids to sell swampland — a Dutch team wants to build Amillarah Private Islands, 29 lavish floating homes and an “amenity island” on about 38 acres of lake in the old North Miami Beach quarry connected to the Intracoastal Waterway just north of Haulover Inlet.

The villa flotilla, its creators say, would be sustainable and completely off the grid, tricked out to survive hurricanes, storm surge and any other water hazard mother nature might throw its way. Chic 6,000-square-foot, concrete-and-glass villas would come with pools, boathouses or docks, desalinization systems, solar and hydrogen-powered generators and optional beaches on their own 10,000-square-foot concrete and Styrofoam islands.

Asking price? About $12.5 million each.

If this sounds like a joke, think again. This, as the Dutch say, ain’t no grap.

“We’re serious people,” said Frank Behrens, vice president of Dutch Docklands, which has partnered with Koen Olthuis, one of Holland’s pioneering aqua-tects.

Still, it’s hard not to be skeptical.

“It’s both fantastic and fantastical,” said North Miami Beach City Planner Carlos Rivero, before adding, diplomatically, “This is quite a departure.”

Behrens won’t say exactly how much the company has invested so far but suggested it is enough to take the plan seriously.

“Look who I’m sitting next to,” he said during an interview, pointing to Greenberg Traurig shareholder attorney Kerri Barsh and Carlos Gimenez, a vice president at Balsera Communications and son of the county’s mayor, both hired to help ensure the project’s success. “This isn’t like, ‘Oh, let’s buy a lake and do a project and make money.’ It’s ‘Let’s buy a lake and show people what we’re capable of.’ ”

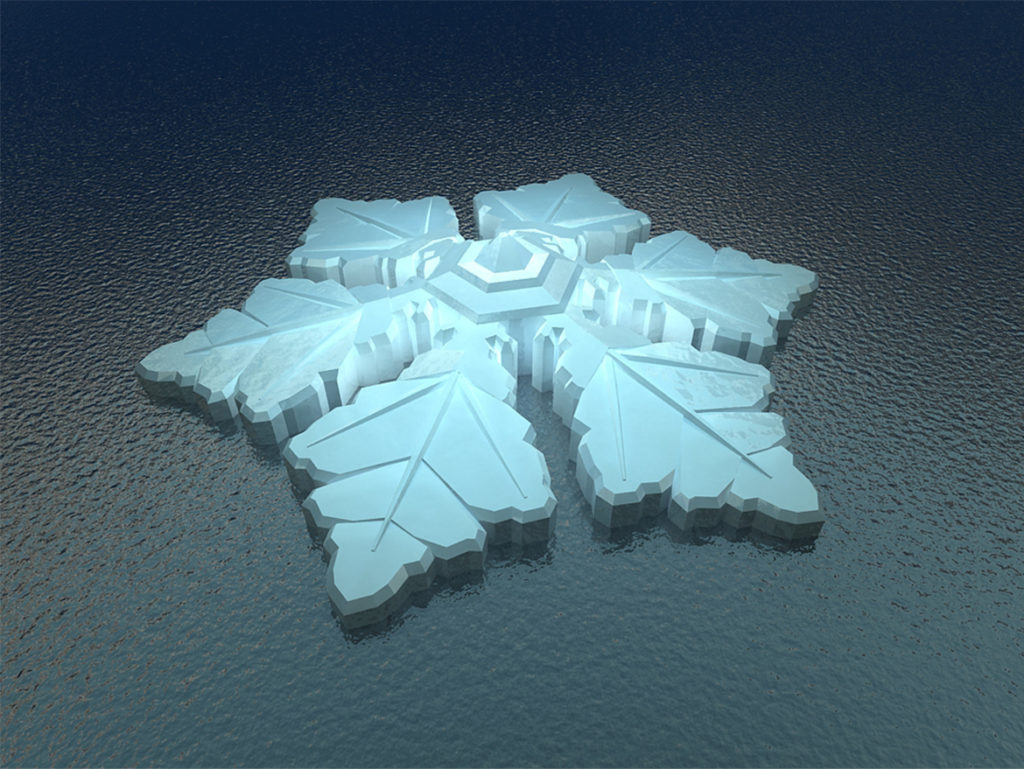

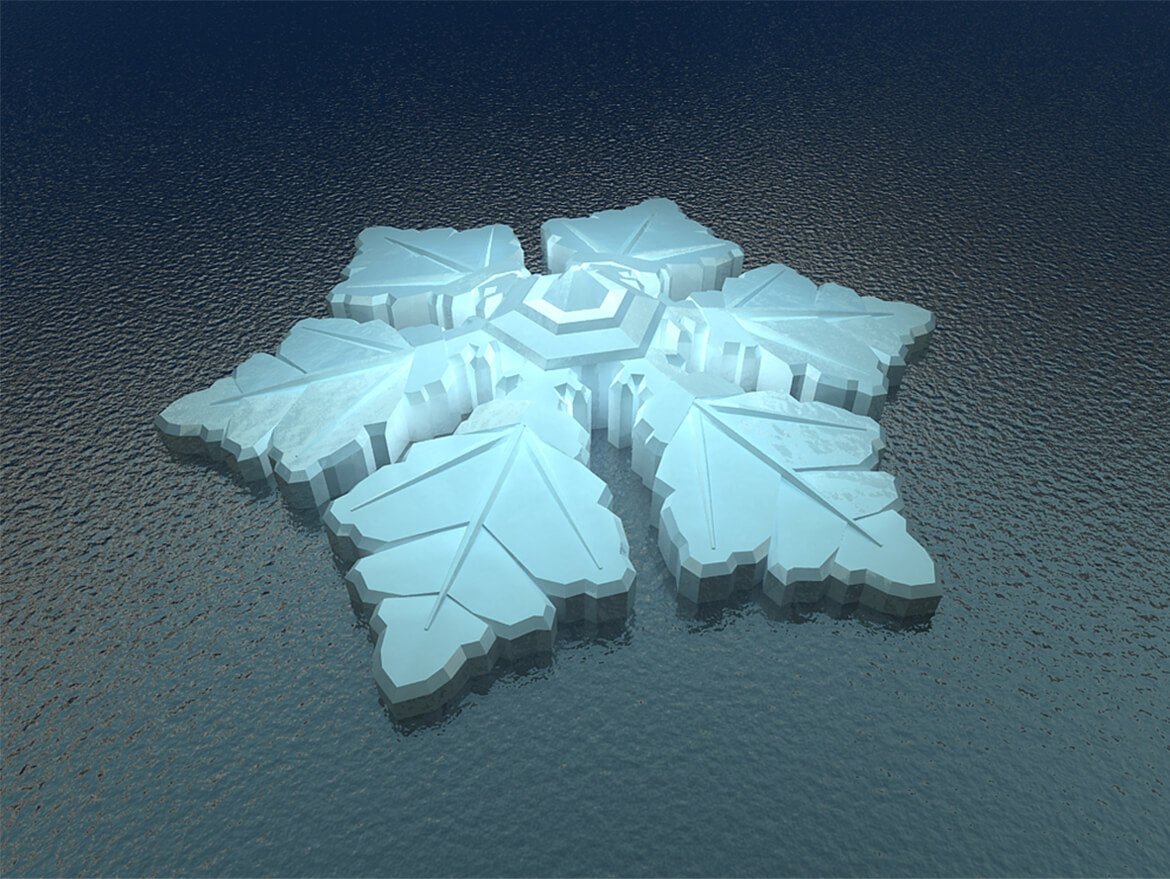

Together Dutch Docklands and Olthius’ firm, Waterstudio.NL, have completed between 800 and 1,000 floating houses in Holland along with 50 other projects including — if there were any question about their design chops —a floating prison near Amsterdam. The team is also constructing the first phase of a 185-villa floating resort in the Maldives — Behrens said 90 have already sold. Olthius also designed a snowflake-shaped floating hotel in Norway, floating mosques in the United Arab Emirates and even a floating greenhouse out of storage containers usually used by oil companies.

The team believes that by building an extreme example of a floating house in Miami, with every bell and whistle imaginable, it can open up a new American market to a way of building that has addressed rising waters in the Netherlands for a century.

“We chose Miami because we know this city is one of the most affected cities by sea-level rise,” Olthuis said by phone from Holland. “Once it’s done, you’ll see it’s a beautiful archipelago effect in the lake.”

So can you get a mortgage? Buy windstorm insurance? Declare a homestead exemption?

Yes, yes and yes, Barsh said. Practically speaking, the barge-like structures are considered houses, not boats, she said. A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision on a Riviera Beach houseboat that Barsh helped argue cleared the way by declaring floating homes real estate. After the victory, Barsh started talking to Behrens — they met through the Dutch Chamber of Commerce he founded in Miami in 2011 — about Dutch-style floating homes in the United States.

“Before, there was a lack of clarity,” Barsh said. The court decision “opened up an opportunity for this development to go forward.”

Barsh, who also represents rock-mining interests, says such projects could potentially provide a valuable way to reuse rock pits scattered throughout South Florida.

But what would it mean for the manatees that lumber through the saltwater lake, which is designated critical habitat?

Protections would remain in place, the team said. And the islands, with specially contoured undersides, could provide a habitat for sea life, Behrens said.

Still, making the project fit local laws could be tricky. In a preliminary review by the North Miami Beach city staff, Rivero raised questions as mundane as the need for parking. The city’s civil engineer wondered about stormwater runoff, among other things. And police say they would need a boat from the developer to patrol the islands. There’s one other thing: North Miami Beach’s rules for such developments so far apply only to land.

Luis Espinoza, spokesman for the county’s Division of Environmental Resources Management, said county officials would need to evaluate the islands for environmental impacts. And there’s the matter of taxes.

“If it’s a permanent-type fixture, then it will be assessed as property,” property appraiser spokesman Robert Rodriguez said.

Over the next 100 years, scientists predict climate change will alter water on a global scale. Seas will swell and coasts will shrink. Weather will become more extreme, with stronger hurricanes, harder rains and higher floods. Even routine tides will rise. And almost nowhere else will those effects likely be more dire than in South Florida, where beachfront highrises and marshy suburbs sit on soggy land kept dry by a complicated network of canals, culverts, pumps and other controls.

So solving the problems of coastal living in the 21st century could be lucrative.

“Here in Miami, it’s an artificial landscape, manipulated by mankind at a very high cost,” said Dale Morris, an economist with the Dutch Embassy in Washington, D.C., who is not connected to the Amillarah project. “So to think it can be maintained at no cost is nuts. I’m an economist. Nothing is free in this world.”

The floating islands, he pointed out, do nothing to solve larger climate problems for cities in South Florida, where flooding now occurs with normal high tides in Miami Beach.

Florida, like Holland, will have to tackle gradual sea rise in addition to event-related flooding like hurricane storm surges, Dutch landscape architect Steven Slabbers said at a recent workshop on resilient design in Miami.

“It’s an inexorable, decade-by-decade phenomenon,” he said.

Considering other Dutch designs — protective dunes tunneled out to hold parking, parks that become ponds and highways that float — a rock-pit-turned-floating-housing by using drilling rig technology might not seem so farfetched.

In recent months, the last new project on Maule Lake, Marina Palms, has shown that demand for lakefront property with Intracoastal access is high. Condos in the first of two buildings, which got the glam treatment this year on Bravo’s Million Dollar Listing Miami, sold out. But Maule Lake has not always been a twinkling star in the real estate firmament. It began life as a rock pit, when E.P. Maule moved from Palm Beach in 1913. Maule Industries would become the state’s largest cement manufacturing plant before falling into bankruptcy in the 1970s after it was purchased by Joe Ferre, whose son, former Miami Mayor Maurice Ferre, managed the company.

“That area was rich in rock pits, quarries and concrete manufacturing,” explained historian Paul George, who said the rock pits pocked the largely industrial area well into the 1960s.

The porous limestone mines fill with water from the area’s high water table. The new lakes provided even more waterfront property to an area already rich with water views, creating a developer’s dream — and possibly an environmentalist’s nightmare.

In addition to worries about marine life, building on the lake may raise concerns about water quality and potential effects on the nearby Biscayne Bay aquatic preserve and the Oleta River, another protected ecosystem. There might also be a question of encroaching on some of the area’s rare open space.

“We have a history in South Florida of viewing open spaces as a pallet for more product to be built on,” said Richard Grosso, a Nova Southeastern University law professor and director of the Environmental and Land Use Law Clinic. “Florida’s always been a place where we’ve suspended the laws of nature and physics and people haven’t always taken into account that there’s a finite amount of space.”

Gimenez, the public relations executive who is also a land use attorney, said the Dutch team has already met with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about concerns. The team also plans to meet with neighbors. And while nothing has officially been submitted, he said no one has raised objections. The 7- to 13-foot-deep lake, he pointed out, is too deep to harbor much marine life or sea grass.

Gimenez also said floating islands are better than the alternative: filling the lake and building highrises. Once mined, rock pits are sometimes refilled with construction and demolition debris. Developers in Hallandale Beach, for example, are filling a 45-acre lake with debris to build an office park. Rivero, the planner, said a North Miami Beach ordinance prohibits the lake from being filled, although property trustee Raymond Gaylord Williams, who had the property listed with a local Realtor for $19.5 million, could challenge that.

But getting a variance from a county ordinance regulating waterways could be a feat, since so few are granted, said land use and environmental attorney Howard Nelson.

“Let’s face it, [what developer] wouldn’t rather replace a houseboat with a houseboat office,” he said. “All of a sudden you don’t have the bay anymore. You just have dock space after dock space after dock space with offices.”

Behrens, a former banker who grew up in Aruba and was CEO of a Miami-based Dutch distillery, said the team has been meeting with various regulatory agencies to size up the obstacles since 2013 and will resolve issues as they come up. They hope to have permits completed within the next year and a half, he said.

“It’s a step-by-step approach,” he said. “But we’re Dutch. …We know how to stay and how to make success.”

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!

Sea levels are rising, floods are prevalent, and cities are at greater risk than ever due to climate change. Now that we’ve accepted these facts, it’s time to design and build more resilient structures. Koen Olthuis, one of the most forward-thinking and innovative architects out there, has a solution for rising sea levels. His solution: Embrace the water by incorporating it into our cities; creating resilient buildings and infrastructure that can handle extreme flooding, heavy rains, and higher water. Olthuis and his team at Waterstudio.nl have been showing coastal communities the benefits of building on the water. With countries like the Maldives and Kiribati having to build oceanside or move in order to escape rising sea levels, New York learning to battle storm surges, and Jakarta dealing with massive flooding, embracing water may be our only option for survival. We chatted with Olthuis about how coastal cities can become more resilient in the face of change—read on for our interview!