Nederlander wil drijvende steden aanleggen in VS

AD Haagshe Courant, Stijn Hustinx, Sep 2013

Een Nederlands bedrijf wil drijvende steden bouwen voor de kusten bij Miami en New York. Vandaag ontvouwt Dutch Docklands zijn plannen. ‘De bedoeling is dat nog dit jaar de eerste contracten worden ondertekend’, zegt Paul van de Camp van het bedrijf tegen het AD.

Dutch Docklands begint ‘klein’, vertelt Van de Camp aan het AD. ‘We hebben bij Miami net een meer van 75 hectare gekocht waar we zestien privé-eilanden willen aanleggen ter waarde van 200 miljoen dollar.’

‘Eilandfundering bestaat uit grote plateaus van schuim en beton’

Op termijn zou het concept kunnen uitgroeien tot compleet drijvende steden, met woningen, scholen, kantoren, winkelcentra en hotels. ‘In landen als Japan en Thailand bestaan drijvende steden al sinds mensenheugenis. Samen met onder meer TNO hebben we grote eilandfunderingen ontwikkeld. Het gaat om drijvende lichamen die bestaan uit grote plateaus van schuim en beton en die kun je zo veel als je wilt aan elkaar vastmaken. Dus of je nu één hotel op een klein drijvend eilandje wilt of een complete stad, het kan. Al zou ik het zeker niet simpel willen noemen. Het lastigste aspect is om de boel te stabiliseren.’

Naast kust Miami ook New York en New Jersey

Het Nederlandse bedrijf heeft niet alleen zijn oog laten vallen op de kustregio van het zonovergoten Miami, maar heeft zich ook gemeld in wereldstad New York en de staat New Jersey om daar drijvende eilanden te gaan bouwen. Plekken die vorig jaar nog hard werden getroffen door superstorm Sandy en het wassende water.

Het is niet zonder reden dat de Nederlanders zich juist hier melden. Op basis van recent onderzoek is een mondiale top 5 samengesteld van rijkste steden die het hardst getroffen zullen worden door de stijgende zeespiegel. Die werd eerder deze maand gepubliceerd door National Geographic. Op nummer 1 staat Miami, New York neemt de derde plek in op de ranglijst. Van de Camp zegt dat hij concrete gesprekken voert met instanties in Miami en New York. Hij verwacht dat nog dit jaar de eerste contracten worden ondertekend.

Minister Schultz van Haegen ook in New York

De ondernemer is niet de enige Nederlander die in de VS munt wil slaan uit de stijgende zeespiegel. Vandaag trappen minister Melanie Schultz van Haegen (Infrastructuur en Milieu) en haar Amerikaanse ambtsgenoot Shaun Donovan een tweedaagse conferentie in New York af, die gaat over kustbescherming.

Nederlandse bedrijven staan sinds superstorm Sandy vorig jaar toesloeg in de rij om New York te helpen te beschermen tegen het water. Dat gebeurde ook al in New Orleans, nadat orkaan Katrina daar in 2005 voor grote overstromingen had gezorgd.

Duurste golfbaan

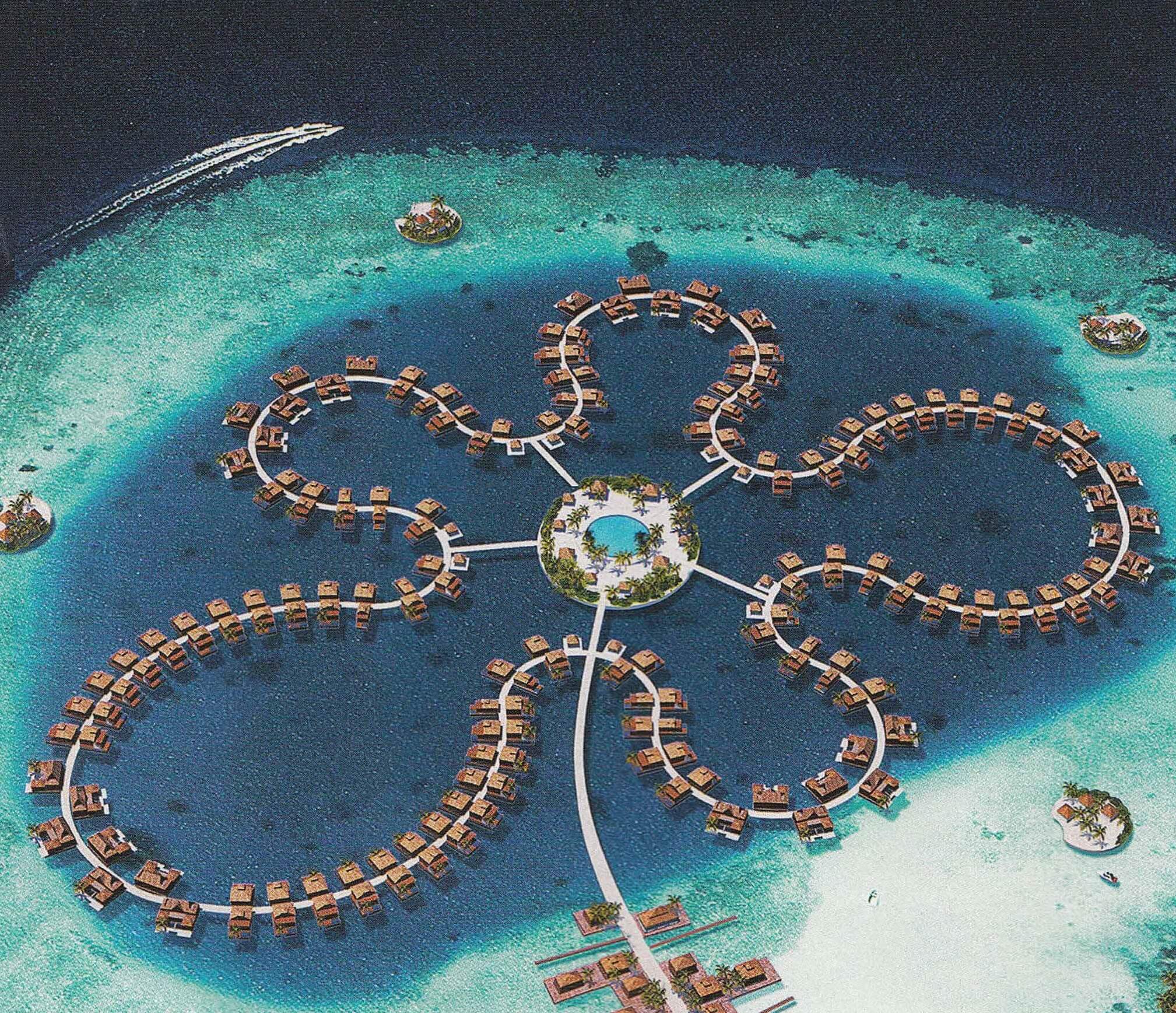

Dutch Docklands wist een paar jaar geleden al de aandacht op zich te vestigen met de aankondiging van de duurste golfbaan ter wereld, ter waarde van 500 miljoen dollar (ruim 350 miljoen euro) bij de Malediven. Deze golfbaan omgeeft een drijvend stadje van enkele honderden woningen.

Hoewel er op papier al de nodige projecten zijn gelanceerd, krijgt het eerste nu ook echt concreet vorm bij de paradijselijke eilandengroep in de Indische Oceaan, die onder de zeespiegel dreigt te verdwijnen. Dutch Docklands gaat daar vijf lagoons ter grootte van de binnenstad van Delft volbouwen. De eerste wordt eind volgend jaar al opgeleverd.

Meet the man who builds things on water, from slum schools to $14 million villas

Quartz, Siraj Datoo, Aug 2013

Dutch architect Koen Olthuis specializes in building things that float. His structures, he concedes, use a similar technology to oil rigs. Yet Olthuis’s focus is elsewhere—on combating rising sea levels, floods, and a growing world population. As he outlined in a TEDx Warwick talk last year, the work he’s doing is quite literally putting land where there wasn’t any before.

Olthuis is the founder of architectural firm Waterstudio.NL, and as a native Dutchman, he often cites his own country’s history as inspiration. “In Holland, we have always been fighting against the water… 50% is under sea level,” he said in his talk. Yet he finds this ongoing battle with water “strange”, arguing that it makes the country susceptible to danger. “What if something breaks?” he said in a phone call with Quartz. His solution: “Why don’t we just use the water?”

His projects include designing homes in Holland, schools in slum neighborhoods in Bangladesh, “amphibious houses” in Colombia, a star-shaped conference center, and a 32-island golf course (with, yes, underwater glass tunnels linking the islands) in the Maldives. He’s also looking to sign a contract to design villas in Florida.

How does it work?

There are three main elements here. The floating base:

[It] is the same technology as we use in Holland. It’s made up of concrete caisson, boxes, a shoebox of concrete. We fill them with styrofoam. So you get unsinkable floating foundations.And the bit on top?

The house itself is the same as a normal house, the same material. Then you want to figure out how to get water and electricity and remove sewage and use the same technology as cruise ships.

How it is anchored to the ground?

In Dubai, they just put sand into the water and made artificial islands. Once you put sand into the water, you can’t go back. We can go back after 150 years and there’s no damage to the habitat.

That’s impressive. So what do you do exactly?

[In the Maldives], these houses are connected to a floating boulevard… Those are connected to the sea bed with telescopic piles and as the boulevard rises up from sea level and the house rises up.And all that means that if there’s a rise in the sea level, due to a flood or tsunami, the island will just rise?

Yes.

“We don’t believe in donating money,” he tells me. “It didn’t work in the history [sic] and it won’t work in the future.” When you give money to charity, he argues, you rarely know what impact it has had.

His response to this is the City Apps Foundation. Instead of donating money for food and aid, companies provide financing for “apps”—interchangeable, prefabricated units such as classrooms, social housing, first-aid stations, or even parking lots. Like the apps on a smartphone, they’re designed to be easy to install and launch with the minimum of fuss. After an initial free trial, schools, governments and local municipalities can lease specific “apps” for a monthly fee. The fees yield a return for the investors, and when the apps are no longer needed they can simply be packed away and assembled in another city. The foundation has raised funding from a number of Dutch companies, and Olthuis and his company provide the technology.

The foundation’s first major project is a school in a slum in Dhaka. Olthuis says that slums have specific problems that appeal to him—in particular their instability. At any moment “the government can say that we’ll take the slums out or landlords might kick them out,” so slum-dwellers tend not to invest in their communities.

City Apps gives power to these neighborhoods, Olthuis argues, especially because they are often situated on the edge of water. In Dhaka, the school app will be a white container that stands out from the rest of the slum to create what Olthuis, perhaps inadvisedly, calls a “shock and awe effect”. The schools will contain iPads for use by the students, and women will use the space for evening classes. Within 12 weeks, the schools will have been built, transported to Dhaka, assembled and ready to use. If the community is forced to move, the school can move too with relative ease.

Olthuis says there are two ways that the City Apps foundation is a better system for investors:

It provides accountability. Cameras inside the containers will allow investors in the project to show off the fruits of their social spending to clients or shareholders in real time.

Although the initial school app will be free, slum-dwellers will have to pay to lease extra apps, such as what Olthuis calls “functions” for sanitation (this could be anything from a toilet to a fully-fledged bathroom) — or even just the ability to print. If the slum no longer wants a specific “function”, it can be easily taken away and used elsewhere. Investors get money if more “apps” are leased

“[It’s] stupid that each [sic] four years, we build complete neighborhoods and then they leave it there.” And it kind of is. The British government spent almost £2 billion ($3.1 billion) on venues alone for the Olympics and Paralympics village for London’s 2012 games. Instead, Olthuis suggests, Olympic cities should lease floating stadiums and property. This could be assembled in advance of the games and packed away afterwards, and would be far cheaper than creating new stadiums and neighborhoods every four years. While it would certainly remove some of the sparkle around the event, it would cut a good deal of waste. In Britain, talk of how the OIympic venues could be used after the games has already faded away.

Work on the “ocean flower”, part of a project that will see 185 new floating villas, has already begun and the first villa will be inhabitable as soon as December this year. Americans, Chinese, Russians and even hotel operators have already forked out the $1 million cost per villa.

Olthuis has a contract with for 42 amillarah islands (private villas in the Maldivian language). These will be 2,500 sq. meters (26,910 sq. feet), and, at $12 million-$14 million, for the “stupidly rich”, Olthuis lets slip.

You can take a speedboat-taxi from the airport in 15 minutes or a three-person “U-boat” submarine will get you there in 40. (Russian president Vladimir Putin was seen modelling the five-person version.) Alternatively, spend three weeks learning how to maneuver a U-boat and a license is yours.

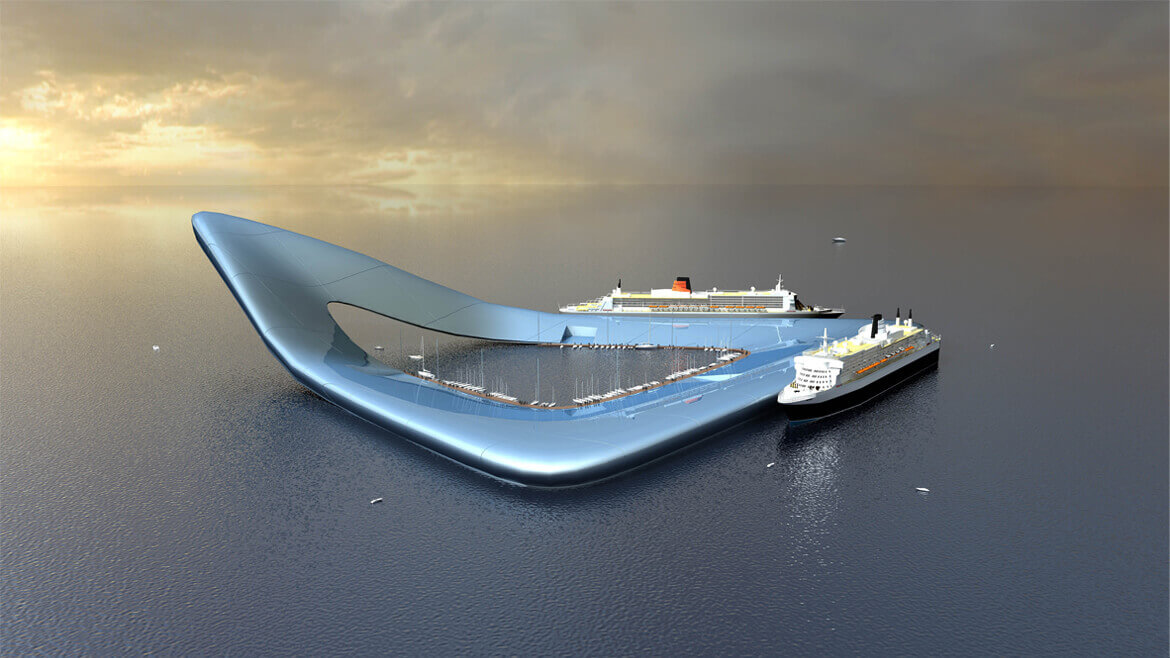

What if there was a hotel-cum-conference center in the middle of the ocean? Construction on this complex will begin towards the beginning of 2014 and with it come some interesting innovations. While a starfish has five “legs”, Olthuis’s company will build six. This means that if a section needs to be renovated, they could replace one leg with the spare (kept at the harbor) within three days instead of having to cordon off the area for months.

In his TEDx Warwick talk, Olthuis jokes that even if you’re on honeymoon in the Maldives, after a few days of glorious swimming, you kind of just want to play golf. And while the golf course might not be swarming with newly-weds, it might attract a new set of tourists from Russia and China.

Even if you’re not much of a golfer, it’s likely you’ll make a trip just to walk in the underground tunnels between the islands. And yes, the tunnel will be transparent.

Colombia has three big flood zones and every time there’s a flood, local municipalities have to pay a lot of money in compensation, according to Olthuis. To combat this, the local government has signed up Waterstudio.NL to build 1500 “amphibian” houses with a floating foundation.

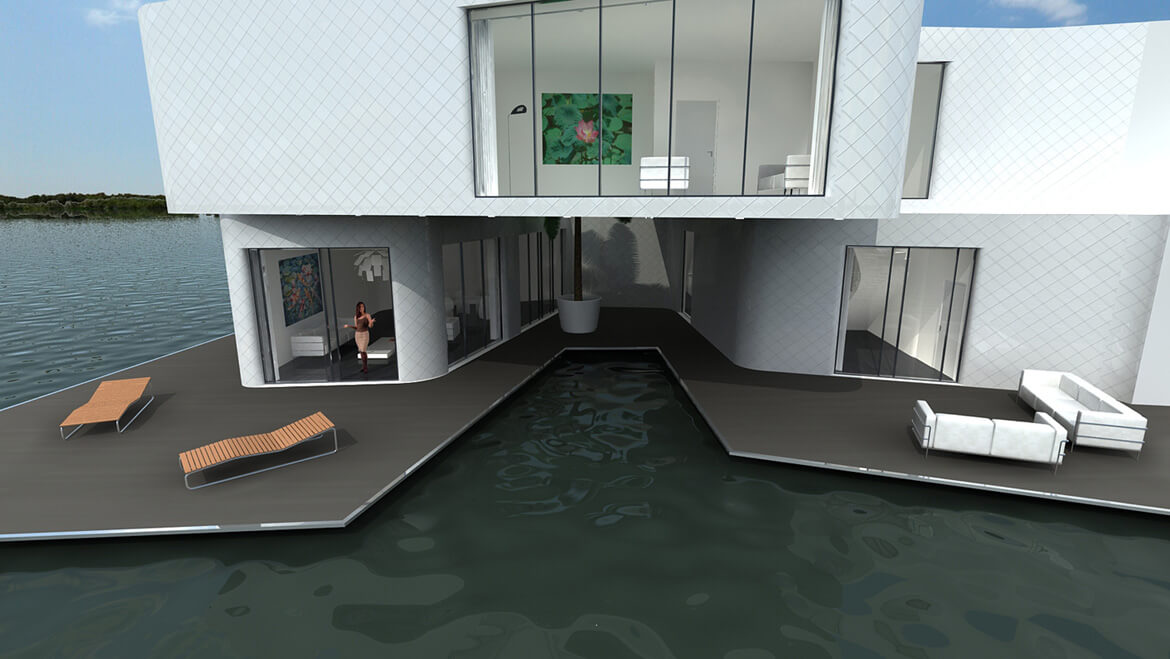

So while the above photo depicts a floating house in a dry season, the house will simply rise in a wet season. While it’s a fairly simple concept, it has radical implications.

Olthuis’s biggest impact so far has been in Holland, where a number of water villas have already been completed. With over 50% of the country below sea level, this provided the perfect playground for his concepts to become a reality

Vivre dans une maison flottante, c’est l’aventure

Le Mond, Audrey Garric, July 2013

Sur sa large terrasse arborée, Rick Uylenhoet profite de la légère brise marine. Ce pilote de ligne de 47 ans, qui passe ses journées dans les airs, a choisi de vivre sur l’eau. Il est le tout premier à s’être installé dans les maisons flottantes qui ont jeté l’ancre au cœur des îles d’Ijburg, un quartier de 20 000 habitants du sud-est d’Amsterdam (Pays-Bas).

“J’ai dessiné les plans moi-même”, lance-t-il fièrement, en faisant visiter sa spacieuse et lumineuse villa de 175 m2, sur trois étages, dans laquelle il vit avec sa femme et ses deux enfants depuis 2008. Dans son grand canapé blanc, caressant son chien, il raconte : “Ici, on a l’impression d’être toujours en vacances. L’été, les enfants se baignent devant la maison et découvrent de nombreux poissons. L’hiver, ils patinent sur le bassin. C’est fantastique de vivre sur l’eau : on s’y sent libre.”

Coût de l’embarquement : 650 000 euros pour la maison, soit 3 700 euros le mètre carré, alors que les prix peuvent grimper jusqu’à 7 000 euros dans le centre d’Amsterdam. Ce prix inclut celui de la parcelle d’eau de 160 m² (130 000 euros), donnée en concession par la ville pour une durée de cinquante ans renouvelable.

“EXPLOITER CETTE EAU QUI EST PARTOUT”

Depuis quelque temps, l’horizon de Rick Uylenhoet s’est toutefois voilé. Avec le succès de ce nouveau mode de vie, une trentaine de demeures personnalisées par des architectes ont amarré sur les pontons voisins. A quelques encâblures, de l’autre côté du bassin protégé par une digue, la municipalité a par la suite installé une soixantaine d’autres habitations flottantes, toutes identiques et moins chères.

“Amsterdam cherche à exploiter cette eau qui est partout”, explique Koen Olthuis, architecte du cabinet Waterstudio, qui a construit deux des maisons du quartier. Objectif : s’adapter à la montée du niveau des mers due au réchauffement climatique, mais, surtout, pallier le manque de place – les Pays-Bas enregistrent la deuxième plus forte densité de population d’Europe.

“Les maisons sont désormais trop proches les unes des autres. J’aimerais me sentir davantage dans la nature”, déplore le pilote, en montrant la vue plongeante sur le salon de ses voisins, à travers les immenses baies vitrées.

“AVOIR PLUS DE PLACE”

Cette proximité, Maartje Ramaekers n’en a cure. Au contraire, elle l’apprécie. La jeune femme de 35 ans, conseillère dans le domaine médical, a acheté avec son mari l’une des maisons flottantes récentes, une habitation mitoyenne cubique. “On a l’impression de vivre dans un village. On est très proches de nos voisins, avec lesquels on organise des fêtes, des barbecues, et on s’aide pour le baby-sitting”, s’enthousiasme-t-elle.

C’est pour leur fille, âgée de 2 ans, que la famille Ramaekers a élu domicile dans ce quartier d’Ijburg. “On a emménagé ici à la naissance d’Arte, pour avoir plus de place et lui faire profiter de la nature”, raconte la jeune mère alors que la petite joue dans le bac à sable installé sur la terrasse au ras de l’eau. A l’intérieur de la maison baignée de lumière, les jouets sont partout : depuis la vaste cuisine au rez-de-chaussée jusqu’aux chambres en bas, sous le niveau de la mer, en passant par le salon à l’étage, qui donne sur la terrasse où trône une balançoire. Pour ces 105 m2, le jeune couple a dû débourser 300 000 euros. Un investissement non négligeable. Mais, estiment ces amoureux de la voile, l’impression de grand large est à ce prix. “Vivre dans une maison flottante, c’est l’aventure !”

ÉQUILIBRER LES MEUBLES

Il a ainsi fallu s’habituer à dormir à 1,5 mètre sous le niveau de la mer – dans la “coque” de la maison-bateau – et au roulis en cas de grand vent. “On voit régulièrement les luminaires tanguer”, décrit Maartje Ramaekers. La maison, construite sur un caisson de béton flottant, est fixée à deux piliers solidement plantés dans l’eau, qui assurent sa stabilité tout en lui permettant de suivre le mouvement de l’onde. “Nous avons aussi dû équilibrer les poids de nos meubles avec ceux de nos voisins !”, ajoute-t-elle, en montrant son piano, disposé à l’extrémité du salon. L’hiver, le gel peut aussi s’emparer des tuyaux des arrivées d’eau, d’électricité et de gaz, qui courent sous les appontements. “On vit avec”, assure-t-elle.

Malgré l’attrait du quartier – médias et curieux s’y pressent depuis cinq ans –, certains logements n’ont pas trouvé preneur en raison de la crise économique. La municipalité projette néanmoins de construire de nouvelles habitations flottantes, plus loin vers la mer. Un nouveau quartier dans lequel Rick Uylenhoet se verrait bien emménager. En y remorquant sa maison.

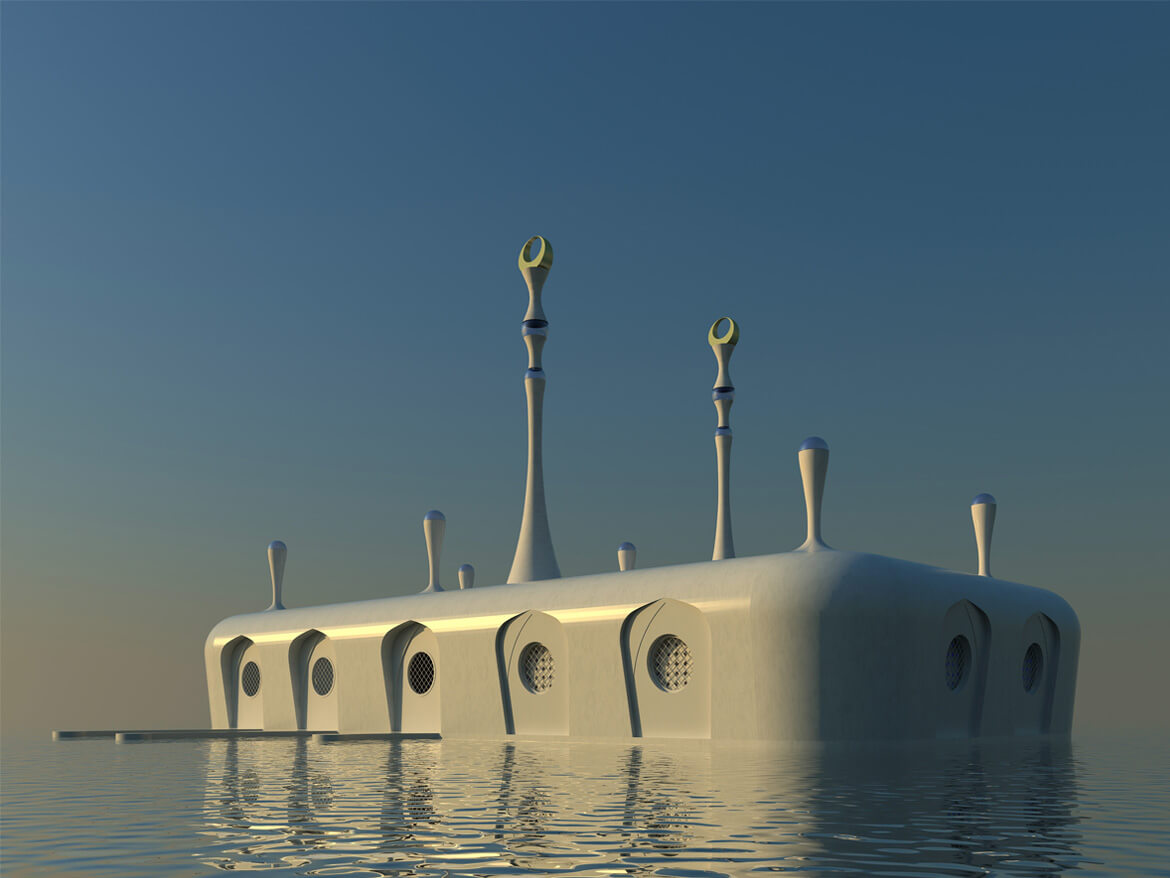

Strange and Bizarre Structures

ABC News

The Citadel, the world’s first floating apartment complex, gives a new meaning to waterfront property. The Netherlands, which is mostly wetlands, faces the issue of pumping out water to protect tracts of land below sea level, known as polders. The Citadel was designed by Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio in the Netherlands as part of the New Water development, an urban development built on a former polder in the city of Westland. Construction for the Citadel will begin in March 2010. When completed, the building will include 60 luxury apartments, a car park and a floating road. The complex will utilize greenhouses and water-cooling techniques to promote environmental sustainability.

The Citadel: Europe’s first floating apartmentcomplex

The Guardian

The Dutch have been fighting the rising and falling tides for centuries, building dikes and pumping water out of areas that are below sea level. Now, rather than fight the water infiltrating their land, the Dutch will use it as part of a new development called ‘New Water’, which will feature the world’s first floating apartment complex, The Citadel. This “water-breaking” new project was designed by Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio in the Netherlands, and will use 25% less energy than a conventional building on land thanks to the use of water cooling techniques.

Olthuis is responsible for a number of floating residences around the world and he thinks that we should stop trying to contain water and learn to live with it. The New Water and the Citadel projects are an attempt to embrace water in the Netherlands, which is almost completely composed of wetlands. The project will be built on a polder, a recessed area below sea level where flood waters settle from heavy rains. There are almost 3500 polders in the Netherlands, and almost all of them are continually pumped dry to keep flood waters from destroying nearby homes and buildings. The New Water Project will purposely allow the polder to flood with water and all the buildings will be perfectly suited to float on top of the rising and falling water.

The Citadel will be the first floating apartment complex, although there are plenty of floating homes out there. Built on top of of a floating foundation of heavy concrete caisson, the Citadel will house 60 luxury apartments, a car park, a floating road to access the complex as well as boat docks. With so many units built into such a small area, the housing complex will achieve a density of 30 units per acre of water, leaving more open water surrounding the structure. Each unit will have its own garden terrace as well as a view of the lake.

A high focus will be placed on energy efficiency inside the Citadel. Greenhouses are placed around the complex, and the water will act as a cooling source as it is pumped through submerged pipes. As the unit is surrounded by water, corrosion and maintenance are important issues to consider. As a result, aluminum will be used for the building facade, due to its long lifespan and ease of maintenance. The individual apartments are built from prefabricated modules. The Citadel will be situated on a shallow body of water, and in the future numerous buildings, complexes and residences will float on the water alongside it.