Gulf News , Sona Nambiar

Being the first human to dedicate his life to living on water and finding solutions to climate change on a large scale, it did not take long for Koen Olthuis or the ‘Floating Dutchman’ to claim global fame. In 2004, it was this very fame that drew the attention of His Highness Shaikh Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai.

“He was one of the first people in the world who saw the unlimited possibilities of floating developments. He took a giant step into the future by envisioning the Floating Proverb [project], consisting of 89 islands, [and covering] more than two million square feet around Palm Jebel Ali,” says Olthuis, who is also the founder of the Dutch architectural practice Waterstudio.

“The Floating Proverb paved the way for mega floating projects worldwide,” he adds. Residential housing, floating landscapes, floating beaches and water-cooled sustainable floating mosques were part of the projected possibilities.

Waterstudio is the architectural partner firm of Dutch Docklands, with offices in Holland, Dubai and the Maldives. Dutch Docklands operates as master planners, being among the first companies worldwide to focus on converting rising seas into prime real estate. It was founded by its CEO, Paul van de Camp, and Olthuis in 2005. Dutch Docklands is now planning floating developments in Holland, Europe, Asia and the Maldives. “Our office in Dubai is still the centre for our global expansion plans for our water-claim portfolio worldwide,” says van de Camp.

GN Focus interviewed Olthuis on how the vision of a floating city is working not just for Holland, but is translating into reality globally.

GN FOCUS: You said recently that “for the climate-change generation of architects, the key will be learning to work with water.” Can you elaborate on this statement?

Koen Olthuis: Urbanisation and climate change put enormous pressure on the world’s growing cities. To keep waterfront cities safe and protected from threats of floods caused by extreme weather, rising sea levels or even tsunamis, you can choose a traditional defensive approach or a more innovative offensive tactic. Now, it is obvious that in a defensive approach, we keep spending money on tackling the sea’s fighting nature with levees. In the offensive tactic, we work with water by designing urban components that are not affected by rising sea levels because they already float. We have to train our young architects to design and innovate dynamic flexible urban developments that see water as a friendly environment instead of fighting nature. The introduction of the elevator 100 years ago radically changed the density of cities. It made vertical expansion in our cities possible. More recently, Dubai opened the eyes of urban planners worldwide with its Palm projects. The next step, therefore, is working with water by creating safety, density and flexibility.

How do floating islands work?

Floating islands are protected against water, as they move up and down with tidal changes, and are flood and even tsunami-proof. Providing new building spaces, their configuration can be adjusted with time, as and when environmental or social issues change a city’s needs.

What percentage of Holland is under water?

Holland, geographically, is an artificial land mass. The Dutch reclaimed it from the sea by building levees around water and swamps and pumping out the water. These are processes that we have to do continuously 24/7, or else the dry land will become wet again. Retaining dry land with the help of thousands of kilometres of levees and windmills, the Dutch managed to enlarge Holland by 35 per cent. A third of Holland is, in fact, under sea level. However, the Dutch have begun to understand that this defensive strategy of making land from water has to be modernised because of the threat of rising sea levels. We now say that if your country is threatened by floods, the safest place to be is on water!

How does it affect a city’s urban planning?

In this urban development strategy, the needs of a city are constantly answered by floating urban components such as floating islands for agriculture, housing, offices, leisure and so on. Configuration, location density and function can be changed. This will lead to new economical opportunities, where governments can cost-effectively lease islands with flexible solutions, instead of investing in static developments. Even if every waterfront city were to expand by only 5 to 10 per cent over urban waters, it would still bring enormous change in the flexibility and density of these cities.

Tell us more about the Citadel project.

The Citadel is planned as the world’s first floating-apartment complex. It is located in the west of Holland and will be deliberately flooded. It can be reached by a floating road, and has a car-storage capacity of 150 cars in the floating concrete foundation underneath the building. The complete building will move up and down as water levels change, but will retain the same comfort levels, lifespan, look and feel of a conventional building. The Citadel is the highlight of a hybrid village comprising 600 floating houses and 600 houses on stilts or artificial hills, which will be protected against the water. The project is scheduled for completion in 2013.

How has this floating city model been used in other countries such as the Maldives?

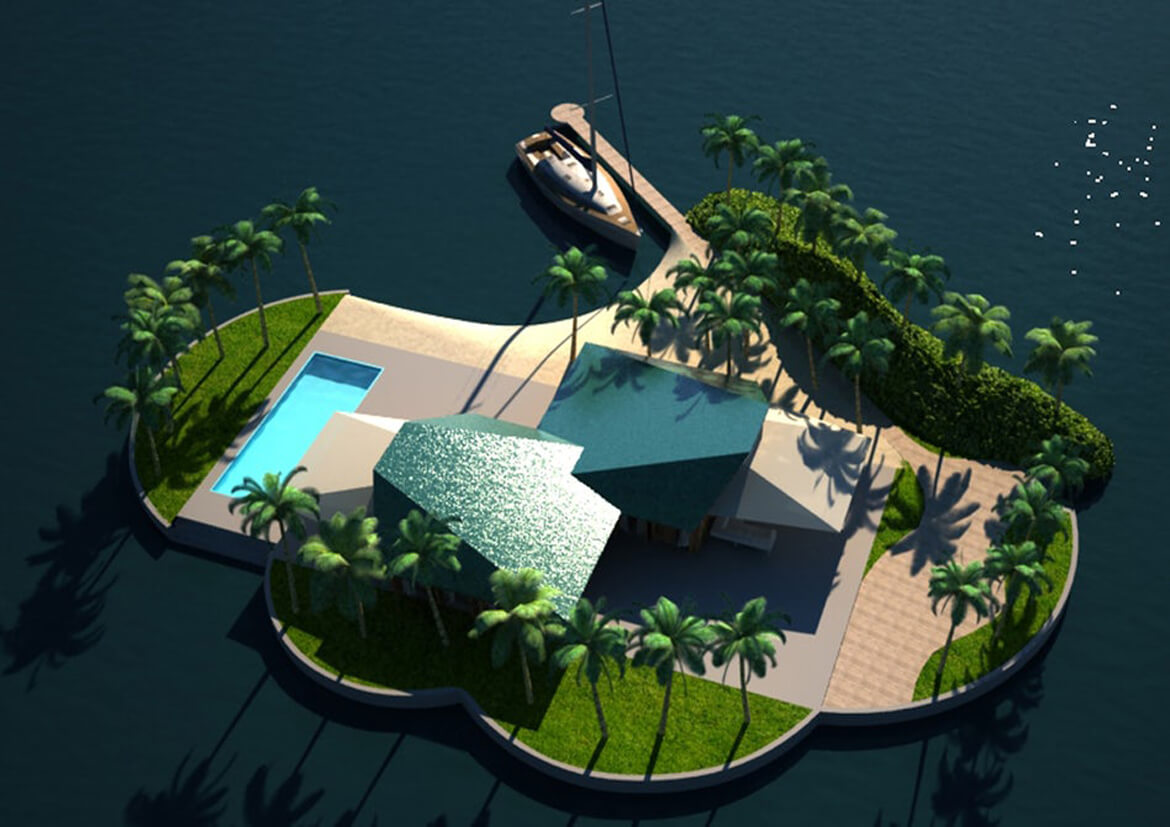

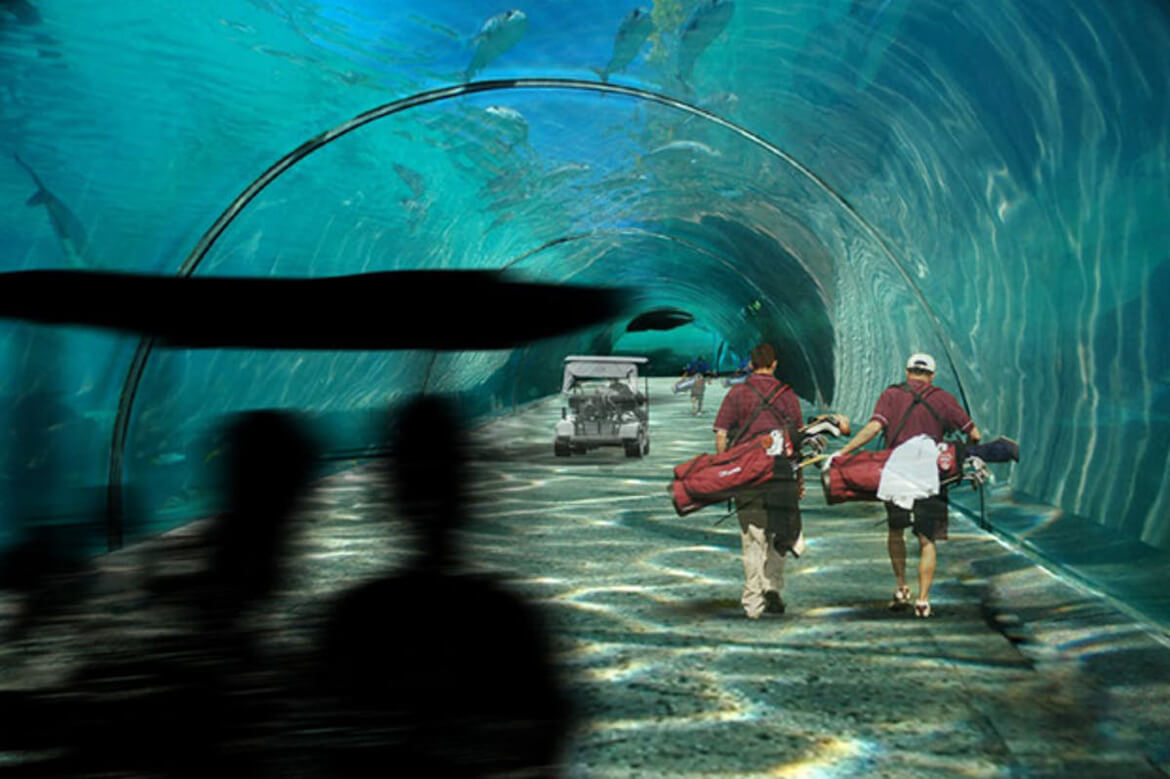

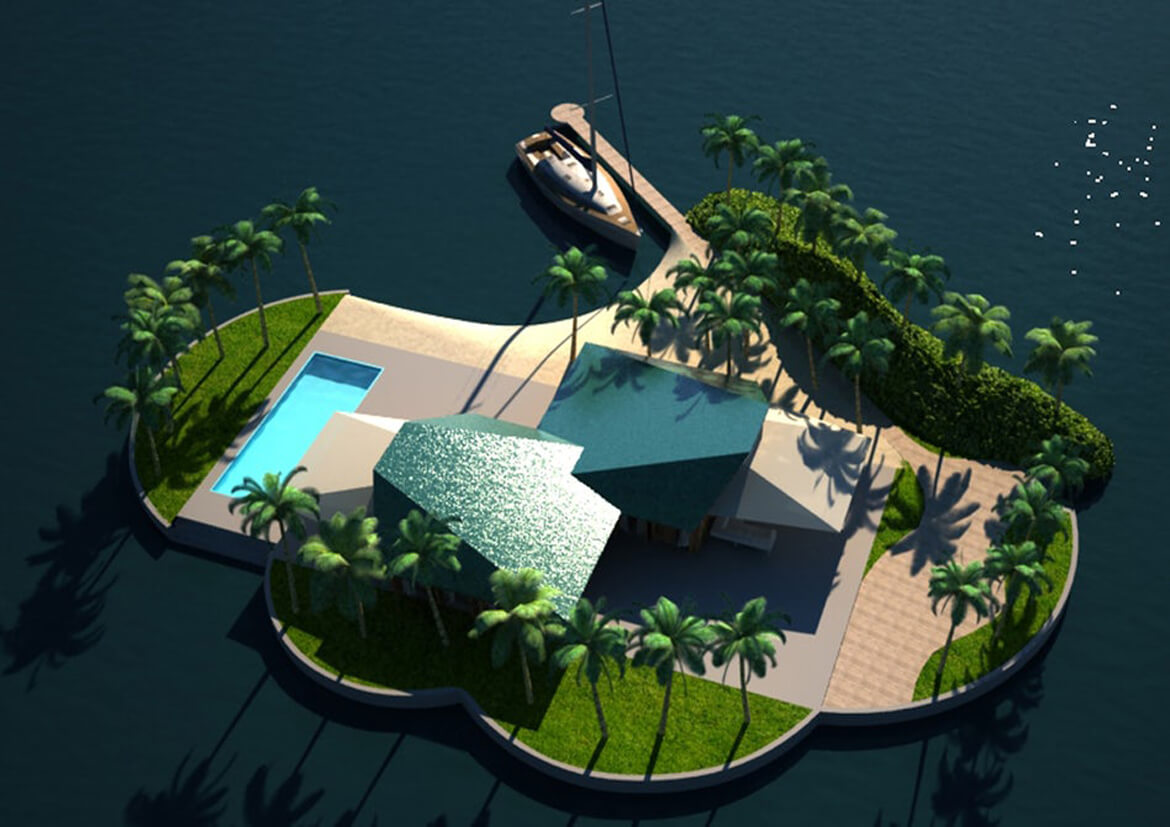

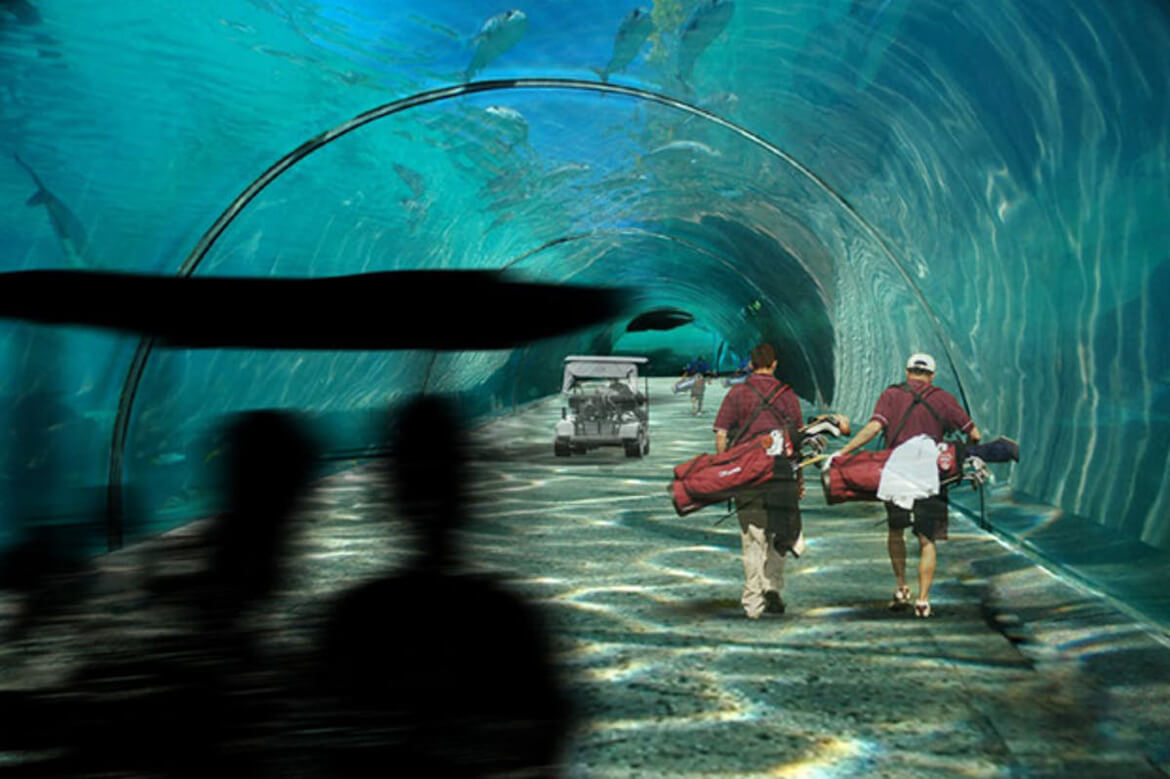

The Maldives might be one of the first countries to more or less disappear when sea levels rise a metre or more in the near future. For them then, it is essential to introduce new ways of building cities on water. Apart from reinforcing tourism by developing leisure projects such as floating hotels and the world’s first floating 18-hole golf course, we are also developing a floating city in the country for the local community through affordable housing. Its president, Mohammad Nasheed, has also set a target to make the Maldives carbon neutral by 2020.

How do floating city concepts integrate with different cultures and climates in terms of building materials?

Due to globalisation, architecture and urban planning have lost out on [their] cultural heritage. Cities worldwide seem to look more alike with each passing decade. We hope to show that our urban plans and architecture would provide either a totally new appearance related to water, or will emphasise the original existing architectural cultural heritage with a floating foundation underneath it. In terms of materials, we can use exactly the same materials for the superstructures on top of the floating islands as those used for developments on the waterfront. So, what are the current technological advances and what is the lifespan of such structures?

Our developments are based on proven floating technology, reinforced by centuries of Dutch know-how on floating structures in Holland that retain the same lifespan as normal land-based developments. We changed the scale of the floating foundations and the quality of the superstructures.

What about infrastructure issues concerning such projects? And waste management?

Our floating islands can be plugged into the existing grid or be self-supporting. “Sustain-aqua-lity” provides us with new possibilities to make more effective sustainable developments. For instance, temperatures on the water in hot countries is always better than on land. Water-cooling and wind-cooling technologies will also open roads for water developments with far less environmental impact. Efficient waste management asks for a multilevel approach and interaction with the waste management on land because of scale purposes. The ultimate goal is to change all forms of waste into an energy resource.

So, how did you get the nickname “Floating Dutchman”?

The Flying Dutchman is a Dutch legend attributed to a ghost ship that can never make it to port and is doomed to sail the seas till eternity. A BBC reporter gave me this name, changing it to the ‘Floating Dutchman,’ while writing an article about our projects. He thought our vision for a floating city would eventually change the way humans perceive the seas.

POLDER POWER

Sited on a vulnerable low-lying river delta, the Netherlands has been prone to floods for thousands of years. Yet, the Dutch have wrested out entire new provinces from its grasp, such as Flevoland, creating a new province in 1986. The story goes back 2,000 years, when the Frisians, early settlers of the area, put in place a series of dikes to hold the water back. A dike failure in 1287 led to floods and the formation of a new bay called the Zuiderzee (South Sea). Since then the Dutch have worked tirelessly to build dikes and polders (reclaimed land) using windmills, canals and pumps to keep the land dry. By the 20th century they had finally beaten back the sea, creating Flevoland. It is this technology that the country’s civil engineers have exported everywhere, including to Dubai’s Palm Islands.

Click here to read the article

Designers have revealed plans for a tourist paradise in the Maldives made up of floating islands that will include hotels, a convention center, a yacht club and a floating golf course.

Designers have revealed plans for a tourist paradise in the Maldives made up of floating islands that will include hotels, a convention center, a yacht club and a floating golf course.