‘Floating Homes’ technology has demonstrated usefulness

By Fane Lozman

Miami Herald

September.10.2014

It is an unfortunate reality that those who currently live on Eastern Shores in Maule Lake will have to abandon their homes in the next 30 years because of rising tides. The only residents around Maule Lake will be the Amirillah floating islands, and any new developments built after Miami 21-like building codes are enacted.

The current Eastern Shores residents should be making plans now for where they will be moving once North Miami Beach condemns their residences for sea water intrusion. Instead, their fears are focused on the floating islands and reflect a total lack of knowledge about floating technology that has been proven over the last century.

Just like floating oil rigs moored to the ocean floor survive Category 5 hurricanes without being torn off their moorings, floating islands use similar technology. The land-based houses around Maule Lake would be swept clean off their concrete pads as the eye wall of a hurricane similar to Andrew made a direct hit, while the Maule Lake floating islands wouldn’t slide an inch off their permanent moorings.

Even more impressive is that these foam-cored, reinforced concrete islands are unsinkable, even after being pelted with 200-mph, windswept debris from the destroyed houses on shore.

The West Coast of the United States has thousands of floating homes that are a welcome addition to their communities in Washington, Oregon and California. The Maule Lake floating-island residences will introduce a new generation of floating homes to the East Coast. They will be completely self-sustaining and have the “greenest” footprint of any dwelling in South Florida.

The landlubbers whose attitude is that “I got to Maule Lake first and no one else should ever join me” forget one thing. The actual lake bottom is privately owned, and the submerged lands do not belong to those who are fortunate to live on its borders. Perhaps a 50-foot-high floating privacy screen running on the east side of Maule Lake would be soothing to these residents so they would not have to be jealous of their floating neighbors?

The floating islands will also help solve a simple reality that the political leaders of North Miami Beach can no longer ignore: New sources of tax revenue will be desperately needed to supplement the hidden pension demands of civil employees (i.e. police) over the coming years.

The 29 floating islands that will be assessed at $12.5 million each will bring in a staggering $363 million in new property assessments. This windfall for the city will be further magnified by the increased tax assessments for the Eastern Shores residents as their droopy neighborhood wakes up to become part of South Florida’s most unique residential community.

Like any new technology, whether it was the Wright brothers’ first airplane flight, or the $3 billon Perdido oil rig anchored in 2,438 meters of water in the Gulf of Mexico, there are “talking heads” that will refuse to accept the inevitable march of technology. It makes one wonder: How many Eastern Shores residents still have horse and buggies in their back yards?

FANE LOZMAN WON A PRECEDENT-SETTING VICTORY LAST YEAR AGAINST RIVIERA BEACH WHEN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT AGREED WITH HIM THAT HIS FLOATING HOME — WHICH THE CITY HAD SEIZED AND DESTROYED UNDER LAWS GOVERNING SHIPS AT SEA — WAS A HOUSE, NOT A VESSEL COVERED BY MARITIME LAW.

De Sea Tree is een stap naar de drijvende toekomst van de natuur in de stad

Joost Mollen

The creatorsproject

September.2014

Voor de mensen die het niet weten: een kamer vinden in Amsterdam is een ramp. De steden hebben nou eenmaal een ruimteprobleem en Amsterdam komt bijvoorbeeld al 15.000 huizen tekort. Maar niet alleen mensen lopen tegen dit woningtekort aan, ook planten en dieren hebben het zwaar. Urbanisatie en klimaatverandering leggen een druk op de beschikbare ruimte voor parken en natuur in stedelijke gebieden. Terwijl er al jaren hard wordt gewerkt aan het vergroten van het aantal woningen in de stad, zijn er helaas maar weinig projecten om nieuwe groene zones te creëren in steden. En dat terwijl parken vet relaxt zijn.

De ultieme oplossing voor dit probleem ligt, wat Waterstudio betreft, op het water. Het Nederlandse architectenbureau is gespecialiseerd in drijvende architectuur en ontwierp eerder al het drijvende ijshotel in Noorwegen en deze superstrakke drijvende villa. Nu wil Waterstudio een heus ‘flatgebouw’ op het water gaan bouwen die speciaal is ontwerpen voor dieren en planten in stedelijke omgevingen. Genaamd de Sea Tree, zal het de eerste drijvende constructie worden die een boost moet geven aan de ecologische systemen van steden. Chillen bovenop de Sea Tree is een no-go want de constructie is afgesloten voor mensen. Maar dat is geen ramp: alleen al kijken naar de ecotoren is genoeg. Hoofdontwerper en medeoprichter van Waterstudio Koen Olthuis nam de tijd om ons meer te vertellen over het project en wanneer we het groene flatgebouw ook in Nederland kunnen verwachten.

The Creators Project: Vertel, waar komt jullie fascinatie met water vandaan?

Koen Olthuis: Op het land had je alle innovatie al. Je deed als architect wat kleurtjes op de muur en stak het gebouw in een leuk vormpje en daar hield het op. Op het water lagen alle mogelijkheden. We zijn ons toen als eerste architectenbureau 100 procent op het water gaan focussen. Na een tijdje dachten we: dit moet niet alleen bij drijvende woningen blijven. We zijn toen gaan onderzoeken hoe steden door middel van drijvende concepten verbeterd kunnen worden. Nu zijn we bijvoorbeeld bezig met drijvende parkeerplaatsen, drijvende stadions en natuurlijk de Sea Tree, een constructie die een enorm positief effect zal hebben op de ecologie van een stad. We bouwen zonder ‘littekens’ omdat je al onze concepten zo weer weg kan varen. We lenen ruimte van de natuur en laten het weer achter zoals het daarvoor was.

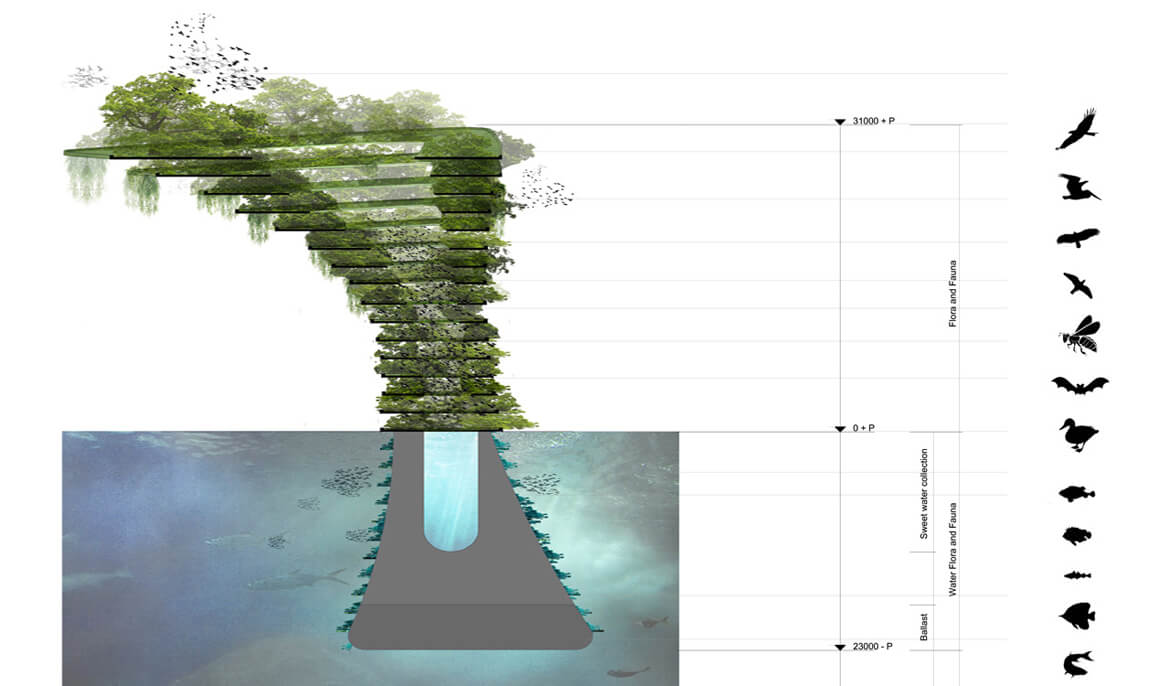

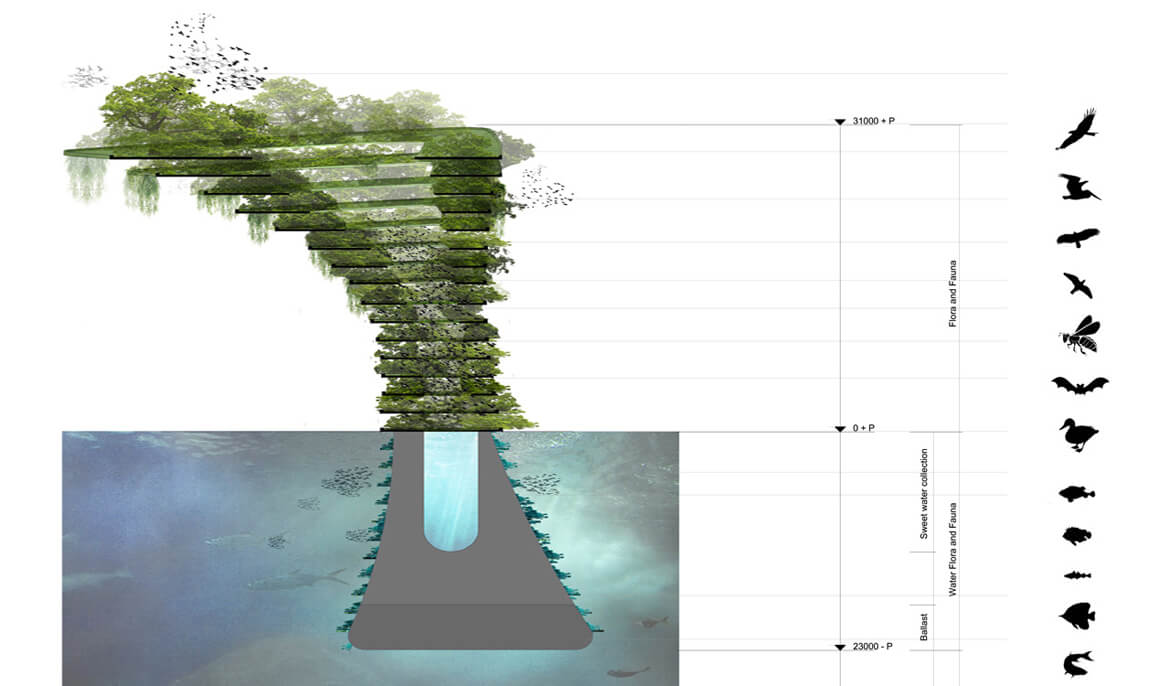

Hoe is het concept voor de Sea Tree tot stand gekomen?

We werden door ecologen gevraagd om een plek te ontwerpen waar de natuur niet verstoord kon worden door mensen. We hebben toen op basis van technologie die door oliemaatschappijen wordt gebruikt een concept gemaakt waarin we de parken van een stad als het ware in de vorm van een boom op elkaar stapelen. Je kunt de Sea Tree het beste vergelijken met die Red Bull-autootjes die overal rondrijden. Dat is rijdende reclame. De Sea Tree is eigenlijk hetzelfde: het is een hele grote en drijvende groene advertentie voor de stad en de techniek van de oliebedrijven, één die laat zien dat het ook een positief effect kan hebben op de natuur en de stad. Het oliebedrijf behoudt het eigendom van de Sea Tree en de stad wijst een plek aan waar die mag drijven.

Hoe reageren de oliemaatschappijen en steden op het concept? Gaat de Sea Tree ook echt gebouwd worden?

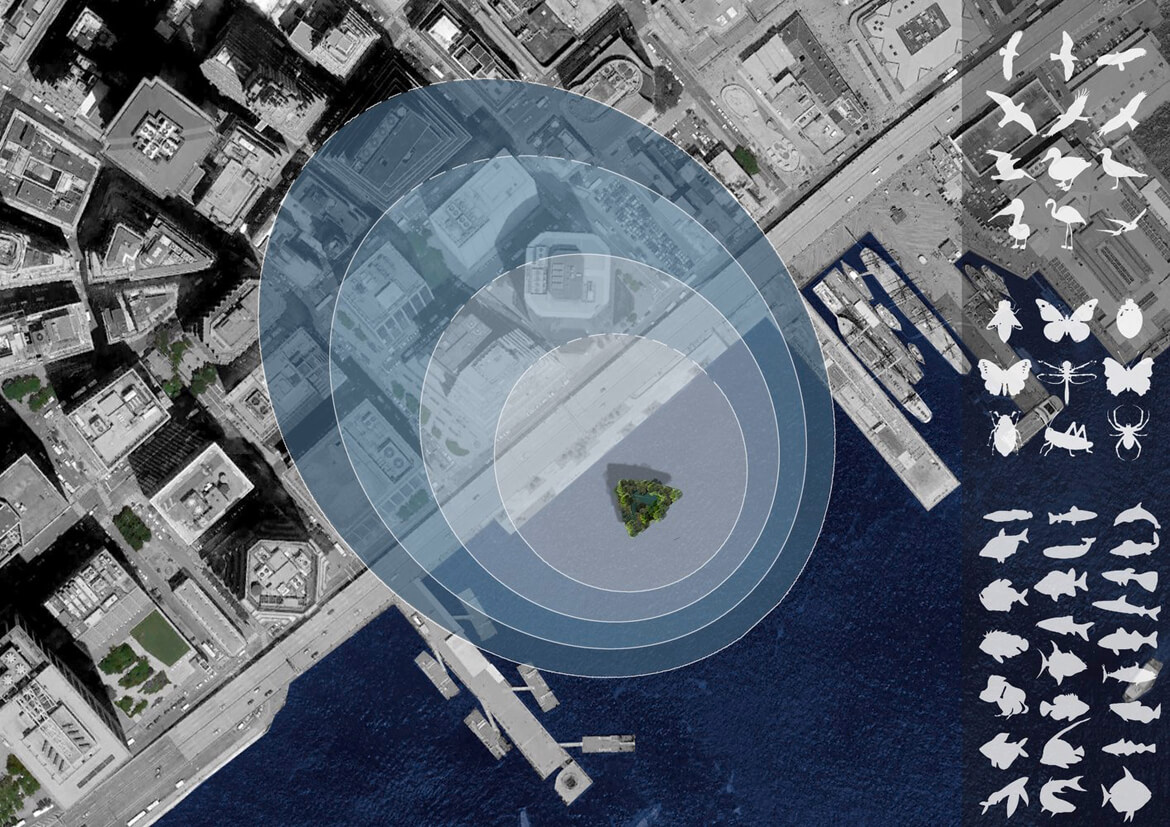

De locatie in steden is geen probleem. We zijn bijvoorbeeld al in Singapore en New York geweest en daar was iedereen super enthousiast. Daarnaast bestaat de technologie ook al. Het punt is dat de bouw van zo’n ding nu al snel één a twee miljoen euro kost en voor dat geld hebben we oliemaatschappijen nodig die mee willen doen. Bij dat soort bedrijven heb je twee soorten partijen werken. Aan de ene kant heb je de mensen van de techniek die het helemaal geweldig vinden. Aan de andere kant heb je de mensen die gaan over de budgeten en advertisement en precies moeten weten wat de positieve en negatieve kanten voor zo’n onderneming zijn. Maar het is heel lastig in te schatten wat voor een effect de Sea Tree gaat hebben. Daar werken we nu aan. Toch zijn we heel positief en denken we dat alles binnen een jaar tijd geregeld kan zijn. Daarna duurt de bouwtijd maar vier tot zes maanden. Het is niets anders dan een drijvende betonconstructie waarop we de natuur haar gang laten gaan.

Als de Sea Tree er ook echt komt, hoe komt het er dan precies uit te zien? Kunnen we hem ook in Nederland verwachten?

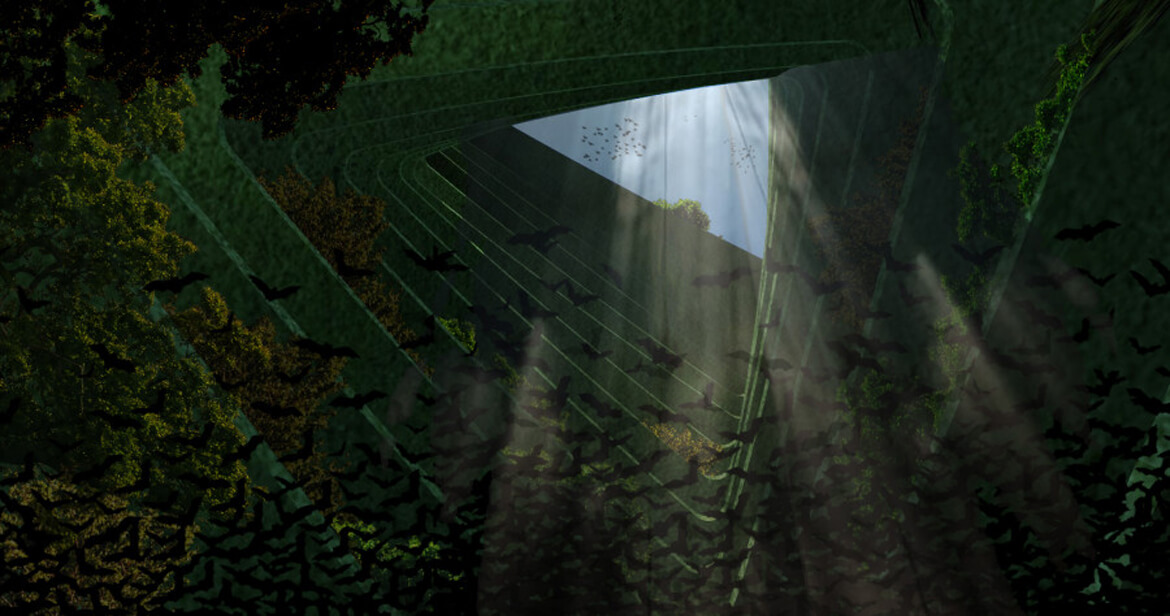

De natuur is enorm veerkrachtig. Het idee is dat we de toren bedekken met voedzame aarde en dan de natuur haar gang laten gaan. We trekken onze handen er af en laten de natuur de Sea Tree zelf begroeien en bevolken. We zien dan wel wat voor een effect het gaat hebben. Het zou bijvoorbeeld de dalende bijenpopulatie een huis kunnen bieden, of een plek kunnen bieden voor vogels waarvoor nu geen ruimte is in de stad. De enige twee dingen die ons tegenhouden om dit bijvoorbeeld in Amsterdam te bouwen zijn in principe alleen de vergunning en het geld.

De Sea Tree is afgesloten voor mensen. Wat hebben we er precies aan behalve het ecologisch voordeel?

Ik kan me voorstellen dat als je in zo’n stad woont het enorm leuk is om naar het bouwwerk te kijken of er omheen te varen, je kunt er alleen niet zelf op gaan. Van een afstand denk je wooooww wat een enorme toren, terwijl het met een hoogte van 35 meter in de stad niet eens zo heel hoog zou zijn. Maar drijvend op het water ziet het er juist heel indrukwekkend uit. Het moet alleen geen geintje worden, zoals die enorme badeend die de wereld over ging. Wij willen ook echt een effect hebben.

U bent heel erg bezig om een plek te vinden voor het ecosysteem van de natuur in de stad. Wat denkt u dat een concept zoals de Sea Tree zegt over de richting waarin de mens de natuur stuurt? Is de Sea Tree een oplossing om de natuur een plaats te bieden in een snel urbaniserende wereld?

Nou oplossing, nee, daarvoor is het effect te klein. Als je werkelijk wilt dat de Sea Tree een effect heeft dan moet je er niet één maar gelijk dertig of veertig neerzetten, zoals we in New York bekeken hebben. Maar het geeft wel een hele duidelijke richting waar we naar toe moeten. Op de lange termijn zie ik niet voor me dat de hele wereld straks vol ligt met Sea Tree’s, absoluut niet, maar het zet mensen wel aan het denken over de mogelijkheden van de natuur op het water, zoals grote drijvende parken of drijvende akkers. De Sea Tree is een symbool voor de eerste stap in die richting. Het is als een enorm groen billboard dat naast een goede boodschap ook nog eens een daadwerkelijk effect op de natuur heeft. Dat is natuurlijk prachtig.

Water Architecture: A chat with Waterstudio and Koen Olthuis

By Enrique Sánchez-Rivera

La Isla

We were intensely captivated by Waterstudio after seeing them featured on National Geographic Magazine. Their incredible innovation skills and clear understanding about the future of architecture and our planet was obvious and ever so present in all of their plans and their current work. From a partially submersed ecological tower to floating islands in the shape of stars, Koen Olthuis and his team are shaping up the future for a post-antarctic ice meltdown era.

How Koen Olthuis is making floating cities a reality

By Sam Becker

Cheatsheet business

August.2014

According to the U.N., approximately 40% of the world’s population lives relatively close to a coastline. Even more than that live in close proximity to rivers and lakes. Together, rivers, lakes, and the sea all offer a wide variety of conveniences, resources, and a method of transportation, making human civilization inherently tied to the water itself. As water has universally been used as a means of exploration and transport for millennia, naturally it makes a fitting tool to use for tackling some of the world’s modern problems, including poverty and medical and education issues.

The question was how to best utilize it. Well, we may have our answer.

One man is revolutionizing the way the world sees cities by bringing a bold new idea to the table. Instead of viewing the idea of cities as static, brick-and-mortar establishments, Koen Olthuis instead likes to imagine them as flexible and malleable — able to adapt to the shifting needs of its citizens. Olthuis has an architectural firm based in the Netherlands called Waterstudio, which has been hard at work creating, among other things, floating houseboats, floating hotels, and even underwater structures. But Olthuis’ true target is the persistent and widespread poverty that sits adjacent to many of the world’s waterways, and use them as a means to deliver help in the form of hospitals and schools.

His idea is called Floating City Apps, which are constructed from recycled shipping containers and built on floating, barge-like structures, ensuring that they are easily moved from place to place, depending on where they are needed. The name comes from the idea of adjusting the apps on a mobile phone according to a user’s needs; City Apps would be able to reconfigure the layouts of slums in the same way.

So, how exactly would Olthuis’ idea work in the real world? As the Floating City Apps blog explains, “first a slum is mapped and local problems are related to water potential in the slum. The Floating City App with the most impact or effect is selected. With the help of our network, licenses and local manager or entrepreneur is selected. The Floating City App will be transported from The Netherlands to the slum.”

After the physical structure itself is shipped to its end destination, local licensees would then take over . “Locally the floating foundation will be built from collected used PET bottles supported by a steel frame. The City App is placed on the function a business model for payed use of the Floating City App is executed in order to get a ROI for the investors. In case of any change in situation the City App can be reused relocated or sent back to The Netherlands.”

In a nutshell, the Floating City App functions as a small business, which is built in the Netherlands and shipped to wherever it is needed. It is then licensed to a local entrepreneur until it is no longer deemed necessary or wanted.

The idea itself is a bit unorthodox, but it does set the wheels in motion for some interesting business models, and could be a very effective way to strategically build in areas of need. In fact, in a way, Floating City Apps open up a route for entrepreneurs to engage the free market in an entirely new way — by offering public services like sanitation or education to places that may be severely lacking.

Imagine a City App anchored dockside near an under-served community that offers Internet access to those who have never had it before? Or even a floating medical center after a natural disaster? The potential applications are numerous, and the idea lends a whole new way to how architects, planners, and engineers can use the topographies of certain cities.

With other factors like climate change leading to impending sea level rises, Floating City Apps may become less of an out-of-the-box idea and more of a necessity in the near future. The idea appears to have merit, and there’s really nothing standing in the way of its feasibility. There are many cities and areas across the world that could benefit from the use of floating service centers. Olthuis himself notes during his TED Talk, seen above, that cities are still built the way they were hundreds of years ago, and engineers need to find a way to take advantage of the water and the space that it provides.

“They’re flexible, they’re reusable, and can work as instant solutions,” Olthuis said of his Floating City Apps. “And they can be much more than only housing. All kinds of functions we can use (them for). Islands, floating beaches, cruise terminal, floating rotating tower, floating roads, agriculture, even a complete floating forest.”

“Almost anything you can think of can also be done on the water,” he adds.

If even a fraction of those ideas are able to be successfully pulled off in the real world, Olthuis’s idea could, in fact, be world-changing. For cities that are located next to large bodies of water and that are densely populated — think locations in Asia or Europe — entirely new neighborhoods could spring up to alleviate congestion and density.

Of all the potential applications, perhaps the most exciting concept is that of floating agriculture. If food production can be brought to dense inner cities bordering bodies of water, fresh and more affordable food would become available to those who desperately need it. Even in America, imagine the advantages a floating corn farm in an inner-city bay would bring to local residents. Granted, there are a lot — a whole lot — of factors to consider. But think of the transportation costs that could be cut out by having a food resource ten minutes away from grocery stores, rather than thousands of miles, in America’s heartland.

Olthuis’s idea certainly is bold, if not ingenious. The next step, of course, will be to see if investors jump on board and if the concept can be put to practical use. Even if Floating City Apps take a long time to gain momentum and take to the waterways of the world’s cities, it’s the kind of thinking being displayed by Olthuis that will truly help change the world for the better.

With the challenges the world’s population is set to face in the coming decades and centuries, we’ll need all the radical ideas we can muster.

Drijvend luxehotel voor Noorse kust

By Architectenweb

August.2014

De kans is groot op een drijvend vijfsterrenhotel voor de kust van Noorwegen. De gemeente Tromsø, ontwikkelaar Dutch Docklands en architectenbureau Waterstudio.NL hebben een overeenkomst getekend.

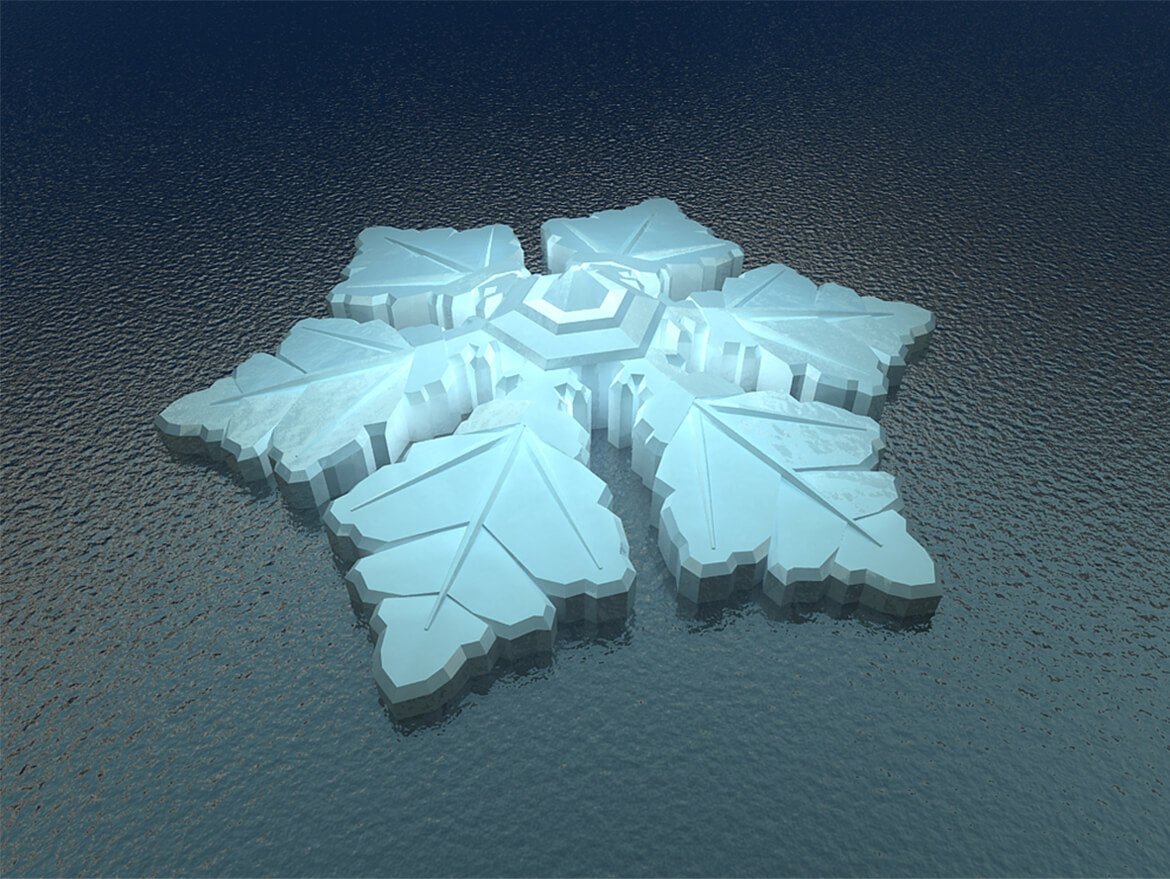

Krystall Hotel moet het meest luxe hotel in het hoge noorden worden, als het aan Dutch Docklands ligt. Het hotel wordt ontworpen als een drijvend ijskristal en moet onder meer 86 kamers bieden. Na een intensief onderzoek naar mogelijke locaties en regelgeving is Waterstudio.NL gestart met het ontwerp van Krystall Hotel.

Het kleine maar bijzondere hotel moet de gasten een bijzondere ervaring met het noorderlicht bieden. Architect Koen Olthuis van Waterstudio.NL vertelt dat daarom een van de uitgangspunten is, dat het hotel een ‘glazen gebouw’ wordt: “Glasdaken voor de kamers zullen het onderscheidende kenmerk zijn”.

Stabiliteit

Het hotel wordt in delen in droogdokken gebouwd en op locatie geassembleerd. Het drijflichaam dat als basis dient zal erg groot zijn; dat zorgt tevens voor een stabiliteit waardoor werknemers en gasten geen beweging voelen. Stabiliteit wordt voorts versterkt door dempers, veren en kabels, maar ook de stervorm van het gebouw.

Het hotel zal geen vaste verbinding met het land hebben; gasten bereiken het Krystall Hotel per boot en ook alle verdere logistiek geschiedt via het water. Omdat het noorderlicht een belangrijke attractie wordt, komt het hotel ver genoeg uit de kust te liggen om de stadslichten van Tromsø geen storend element te laten zijn. De exacte locatie wordt nu onderzocht.

Overeenstemming

De internationaal opererende ontwikkelaar van drijvend vastgoed Dutch Docklands, Waterstudio.NL en de gemeente Tromsø hebben vorige week hun overeenstemming met een handtekening bezegeld. De bouw start naar verwachting half 2015; voor kerstmis 2016 moet het Krystall Hotel worden geopend en geëxploiteerd door een vijfsterren-hotelonderneming.

Stjernearkitekter vil bygge flytende luksushotell i Tromsø

By Nordnytt

August.21.2014

Tromsø kommune har i dag signert en intensjonsavtale med selskapet Dutch Docklands om å bygge et flytende hotell utenfor byen.

Avtalen betyr at kommunen stiller seg positiv til at det femstjerners luksushotellet skal bygges i Tromsø.

Det nederlandske selskapet Dutch Docklands har planer om å bruke 500 millioner kroner på luksushotellet, som skal utformes som en flytende iskrystall, og inneholde 86 rom.

– Vi planlegger å bygge det mest luksuriøse hotellet i den nordlige delen av verden. Det vil bli et unikt femstjerners hotell som vil gi gjestene en opplevelse med nordlyset, men også andre aspekter av Norge og av denne delen av verden, sier Paul van de Camp administrerende direktør i Dutch Docklands.

Selskapet er eksperter på flytende konstruksjoner, og har tidligere blant annet bygget luksushotell på Maldivene.

For pengesterke gjester

Han sier at Tromsø ble valgt på grunn av historien sin, men også på grunn av at byen allerede har utbygd infrastruktur når det kommer til turisme.

– Er det et marked for et slikt hotell?

– Det vil bli et lite hotell, men i den øvre enden av skalaen. Det betyr at romprisene vil bli høyere enn det som allerede finnes på markedet i Tromsø. Vi retter oss mot folk som er villig til å betale for et visst komfortnivå og for å få opplevelser i nordlige strøk. Det er et enormt globalt marked for dette, sier van de Camp.

Nå skal selskapet samarbeide med kommunen om å få på plass de nødvendige tillatelsen, og finne ut hvor det flytende hotellet skal ligge.

Hvor og hvordan det skal bygges er ennå ikke avklart.

– Vi ønsker vanligvis å få gjort mest mulig av dette lokalt. Vi vet at norske håndverkere er kjent for å holde en høy standard, akkurat som nederlandske. Det viktigste for oss er kvaliteten på arbeidet, og får vi dette til lokalt, så støtter vi det, sier van de Camp.

Kommunen positiv

– Vi har skrevet under på en avtale om at vi er positive til at dette hotellet kommer til Tromsø kommune for å etablere seg her. Vi kan bistå med kartmateriale, og når de har funnet fram til hvor de vil at hotellet skal ligge, så kan vi ha et oppstartsmøte, sier Britt Hege Alvarstein byråd for byutvikling i Tromsø kommune.

Hun sier at kommunen nå driver med en revidering av kommuneplanen og en kystsoneplan for Tromsø.

– Vi har ikke tatt høyde for at vi skal ha et flytende hotell i kommunen, så det må vi nå ta høyde for, sier Alvarstein.

Plan- og bygningsloven, reguleringsplaner og ikke minst skipsleden i Tromsø blir førende for hvor hotellet kan ligge, men det blir trolig i en av fjordene rundt byen.

Miljøprofil

– Selskapet har sagt at de ønsker at hotellet skal ligge rundt en times reise unna flyplassen, sier Alvarstein.

Hun peker på at selskapet bak hotellet har en miljøprofil og blant annet samarbeide med UNESCO for å ta vare på miljøet rundt og under der de bygger, så de lager minst mulig fotavtrykk i naturen.

– Det er spennende teknologi som tas i bruk, og ets pennende prosjekt på alle områder, sier Alvarstein.

– Er det ikke allerede nok hotellrom i Tromsø?

– Vi så både under sjakk-OL og Arctic Race at det ikke var rom å oppdrive, så kommunen har ennå behov for flere hotellrom. Men dette er jo et marked som kommer utenom det vanlige. Det vil være med på å forsterke det eksisterende tilbudet i byen, mener Alvarstein.

Dutch solution to Miami’s rising seas? Floating islands

By Jenny Staletovich

Miami Herald

August.23.2014

Maule Lake has been many things over the years: industrial rock pit, aquatic racetrack, American Riviera. Now it is being pitched as something else entirely: a glitzy solution to South Florida’s rising seas.

In the land of boom and bust where no real estate proposition seems too outlandish — Opa-locka’s Ali Baba Boulevard connects to Aladdin Street in one of the more kitschy bids to sell swampland — a Dutch team wants to build Amillarah Private Islands, 29 lavish floating homes and an “amenity island” on about 38 acres of lake in the old North Miami Beach quarry connected to the Intracoastal Waterway just north of Haulover Inlet.

The villa flotilla, its creators say, would be sustainable and completely off the grid, tricked out to survive hurricanes, storm surge and any other water hazard mother nature might throw its way. Chic 6,000-square-foot, concrete-and-glass villas would come with pools, boathouses or docks, desalinization systems, solar and hydrogen-powered generators and optional beaches on their own 10,000-square-foot concrete and Styrofoam islands.

Asking price? About $12.5 million each.

If this sounds like a joke, think again. This, as the Dutch say, ain’t no grap.

“We’re serious people,” said Frank Behrens, vice president of Dutch Docklands, which has partnered with Koen Olthuis, one of Holland’s pioneering aqua-tects.

Still, it’s hard not to be skeptical.

“It’s both fantastic and fantastical,” said North Miami Beach City Planner Carlos Rivero, before adding, diplomatically, “This is quite a departure.”

Behrens won’t say exactly how much the company has invested so far but suggested it is enough to take the plan seriously.

“Look who I’m sitting next to,” he said during an interview, pointing to Greenberg Traurig shareholder attorney Kerri Barsh and Carlos Gimenez, a vice president at Balsera Communications and son of the county’s mayor, both hired to help ensure the project’s success. “This isn’t like, ‘Oh, let’s buy a lake and do a project and make money.’ It’s ‘Let’s buy a lake and show people what we’re capable of.’ ”

Together Dutch Docklands and Olthius’ firm, Waterstudio.NL, have completed between 800 and 1,000 floating houses in Holland along with 50 other projects including — if there were any question about their design chops —a floating prison near Amsterdam. The team is also constructing the first phase of a 185-villa floating resort in the Maldives — Behrens said 90 have already sold. Olthius also designed a snowflake-shaped floating hotel in Norway, floating mosques in the United Arab Emirates and even a floating greenhouse out of storage containers usually used by oil companies.

The team believes that by building an extreme example of a floating house in Miami, with every bell and whistle imaginable, it can open up a new American market to a way of building that has addressed rising waters in the Netherlands for a century.

“We chose Miami because we know this city is one of the most affected cities by sea-level rise,” Olthuis said by phone from Holland. “Once it’s done, you’ll see it’s a beautiful archipelago effect in the lake.”

So can you get a mortgage? Buy windstorm insurance? Declare a homestead exemption?

Yes, yes and yes, Barsh said. Practically speaking, the barge-like structures are considered houses, not boats, she said. A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision on a Riviera Beach houseboat that Barsh helped argue cleared the way by declaring floating homes real estate. After the victory, Barsh started talking to Behrens — they met through the Dutch Chamber of Commerce he founded in Miami in 2011 — about Dutch-style floating homes in the United States.

“Before, there was a lack of clarity,” Barsh said. The court decision “opened up an opportunity for this development to go forward.”

Barsh, who also represents rock-mining interests, says such projects could potentially provide a valuable way to reuse rock pits scattered throughout South Florida.

But what would it mean for the manatees that lumber through the saltwater lake, which is designated critical habitat?

Protections would remain in place, the team said. And the islands, with specially contoured undersides, could provide a habitat for sea life, Behrens said.

Still, making the project fit local laws could be tricky. In a preliminary review by the North Miami Beach city staff, Rivero raised questions as mundane as the need for parking. The city’s civil engineer wondered about stormwater runoff, among other things. And police say they would need a boat from the developer to patrol the islands. There’s one other thing: North Miami Beach’s rules for such developments so far apply only to land.

Luis Espinoza, spokesman for the county’s Division of Environmental Resources Management, said county officials would need to evaluate the islands for environmental impacts. And there’s the matter of taxes.

“If it’s a permanent-type fixture, then it will be assessed as property,” property appraiser spokesman Robert Rodriguez said.

Over the next 100 years, scientists predict climate change will alter water on a global scale. Seas will swell and coasts will shrink. Weather will become more extreme, with stronger hurricanes, harder rains and higher floods. Even routine tides will rise. And almost nowhere else will those effects likely be more dire than in South Florida, where beachfront highrises and marshy suburbs sit on soggy land kept dry by a complicated network of canals, culverts, pumps and other controls.

So solving the problems of coastal living in the 21st century could be lucrative.

“Here in Miami, it’s an artificial landscape, manipulated by mankind at a very high cost,” said Dale Morris, an economist with the Dutch Embassy in Washington, D.C., who is not connected to the Amillarah project. “So to think it can be maintained at no cost is nuts. I’m an economist. Nothing is free in this world.”

The floating islands, he pointed out, do nothing to solve larger climate problems for cities in South Florida, where flooding now occurs with normal high tides in Miami Beach.

Florida, like Holland, will have to tackle gradual sea rise in addition to event-related flooding like hurricane storm surges, Dutch landscape architect Steven Slabbers said at a recent workshop on resilient design in Miami.

“It’s an inexorable, decade-by-decade phenomenon,” he said.

Considering other Dutch designs — protective dunes tunneled out to hold parking, parks that become ponds and highways that float — a rock-pit-turned-floating-housing by using drilling rig technology might not seem so farfetched.

In recent months, the last new project on Maule Lake, Marina Palms, has shown that demand for lakefront property with Intracoastal access is high. Condos in the first of two buildings, which got the glam treatment this year on Bravo’s Million Dollar Listing Miami, sold out. But Maule Lake has not always been a twinkling star in the real estate firmament. It began life as a rock pit, when E.P. Maule moved from Palm Beach in 1913. Maule Industries would become the state’s largest cement manufacturing plant before falling into bankruptcy in the 1970s after it was purchased by Joe Ferre, whose son, former Miami Mayor Maurice Ferre, managed the company.

“That area was rich in rock pits, quarries and concrete manufacturing,” explained historian Paul George, who said the rock pits pocked the largely industrial area well into the 1960s.

The porous limestone mines fill with water from the area’s high water table. The new lakes provided even more waterfront property to an area already rich with water views, creating a developer’s dream — and possibly an environmentalist’s nightmare.

In addition to worries about marine life, building on the lake may raise concerns about water quality and potential effects on the nearby Biscayne Bay aquatic preserve and the Oleta River, another protected ecosystem. There might also be a question of encroaching on some of the area’s rare open space.

“We have a history in South Florida of viewing open spaces as a pallet for more product to be built on,” said Richard Grosso, a Nova Southeastern University law professor and director of the Environmental and Land Use Law Clinic. “Florida’s always been a place where we’ve suspended the laws of nature and physics and people haven’t always taken into account that there’s a finite amount of space.”

Gimenez, the public relations executive who is also a land use attorney, said the Dutch team has already met with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about concerns. The team also plans to meet with neighbors. And while nothing has officially been submitted, he said no one has raised objections. The 7- to 13-foot-deep lake, he pointed out, is too deep to harbor much marine life or sea grass.

Gimenez also said floating islands are better than the alternative: filling the lake and building highrises. Once mined, rock pits are sometimes refilled with construction and demolition debris. Developers in Hallandale Beach, for example, are filling a 45-acre lake with debris to build an office park. Rivero, the planner, said a North Miami Beach ordinance prohibits the lake from being filled, although property trustee Raymond Gaylord Williams, who had the property listed with a local Realtor for $19.5 million, could challenge that.

But getting a variance from a county ordinance regulating waterways could be a feat, since so few are granted, said land use and environmental attorney Howard Nelson.

“Let’s face it, [what developer] wouldn’t rather replace a houseboat with a houseboat office,” he said. “All of a sudden you don’t have the bay anymore. You just have dock space after dock space after dock space with offices.”

Behrens, a former banker who grew up in Aruba and was CEO of a Miami-based Dutch distillery, said the team has been meeting with various regulatory agencies to size up the obstacles since 2013 and will resolve issues as they come up. They hope to have permits completed within the next year and a half, he said.

“It’s a step-by-step approach,” he said. “But we’re Dutch. …We know how to stay and how to make success.”

Amillarah Now affiliate of Christie’s

Amillarah private islands is now officially affiliate of Christie’s International Real Estate

Koen Olthuis speaks on BODW Hong Kong

His speech was very well received at Asia’s largest and leading annual event on design, innovations and brand

Koen Olthuis speaks on BODW Hong Kong

Click here for the website

Koen’s speech in the Culture and the City Session was very well received.

Business of Design Week (BODW) is a flagship event organised by Hong Kong Design Centre since 2002. Each year, BODW brings to Hong Kong some of the world’s most outstanding design masters and influential business figures to inspire the regional audience on creative thinking and design management. In addition, it also provides a valuable platform for participants to network, exchange ideas and explore business cooperation. Today, BODW enjoys the reputation as Asia’s leading annual event on design, innovation and brands.