Citadel in CNN’s top 10 eye-popping buildings

Citadel one of the 10 eye-popping new buildings that you’ll see in 2014

Künstliche inseln

Kultur Austausch, February 2014

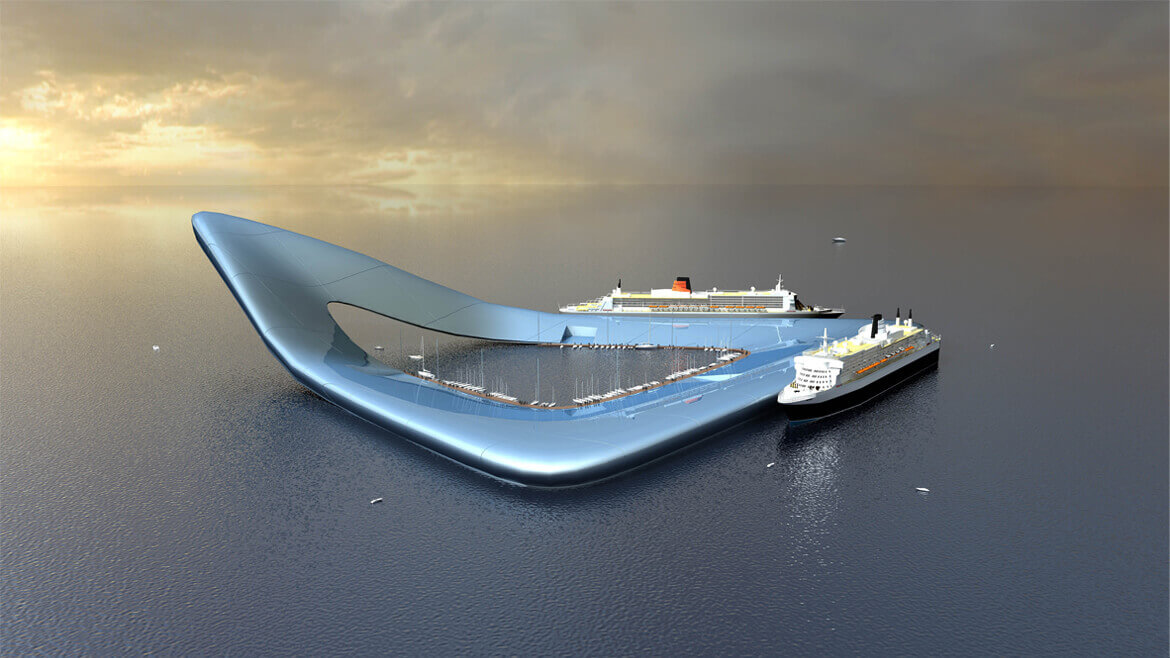

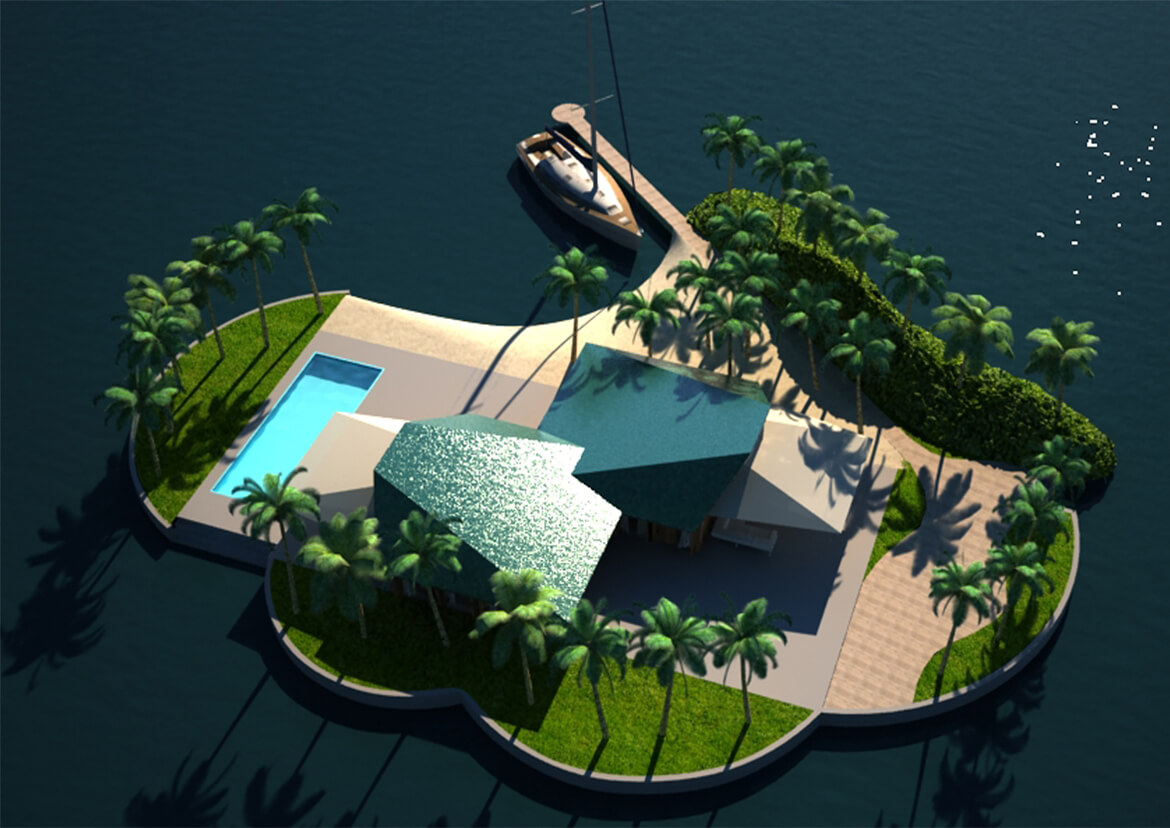

Amillarah is the Maldivian word for Private Island.This unique project exists of 43 floating private Islands in a archipelago configuration.The exclusive Villas all have a private beach, pool and natural green with bushes and trees. A private jetty is the mooring place for the yachts.At the end of each jetty, a small pavilion is situated.A boutique Hotel provides all the needed services to these Private Islands.

How Can We Waterproof Our Future

Inhabitat, Yuka Yoneda, Feb 2014

When the movie Waterworld premiered in 1995, people regarded the Kevin Costner flick as a fairly ridiculous post-apocalyptic science fiction film: Now, nearly two decades later, the tale’s premise of a world where nearly all land is submerged beneath the seas seems more like a prediction of what’s to come than a figment of a screenwriter’s imagination. With polar ice caps melting rapidly, the clear and present threat of rising tides is no longer something that can be pushed aside. According to current scientific estimates, the earth’s temperature will increase at least 4-5 °C by the end of this century, leading to a sea level rise of approximately 2-7 feet or more by 2100, which will submerge significant portions of many of the world’s major metropolitan areas, including New York, London, Shanghai and Mumbai. Since we’re facing some pretty catastrophic changes, some of the world’s best minds are working on solutions to prevent, or at the very least, minimize, the land loss and human habitat destruction that lies ahead. But between dams, water barriers and floating cities, it’s easy to get lost in the “flood” of different options for dealing with rising sea-levels. Bettery Magazine recently broke down our current situation and the various types of approaches which are being tried all around the world to deal with rising waters. Read Bettery’s full report for a better understanding of how we can waterproof our future.

Think Dutch, Build on water

Think Dutch, Robert Thiemann, Jeroen Junte & David Keuning, Dec 2013

Think Dutch! does not make any fundamental distinction between design and architecture. The book groups together the work of the young creative generation into 16 chapters with titles such as “Build on Water”, “Celebrate Food”, “Don’t Create for Eternity” or “Get Educated”. It poses thought-provoking questions such as: “Does this design yield new insight?”, “When does it make sense to use bio-degradable materials in architecture?” and “How can we establish self-sufficient food chains?” It is this critical approach to creative work that has become integral to Dutch architecture and design in recent decades.

This book presents 476 diverse architectural and design projects and products, devised by some of the most creative contemporary minds in this field; all provide positive proof of cutting-edge thinking, and investment in sustainable futures, exciting ideas that are inspirational, leading the way towards a brighter future.

Click here for the full article

Dutch firm says giant floating platforms could ease urban crowding

South China Morning Post,Jamie Carter, November 2013

There has been much debate on where land can be found to house a growing population in Hong Kong. For communities elsewhere, the need is even more pressing.

With global population density increasing and sea levels expected to rise by as much as 30cm by 2050, many coastal habitats will come under intense pressure. And the answer could be right on the horizon.

“In major cities there’s already a lack of space and the next logical step is to make use of water,” says Koen Olthuis, founder of Netherlands-based Waterstudio.nl and architect of multiple maritime projects.

“It’s just evolution – the elevator made vertical cities of skyscrapers possible, and water is the next step for letting cities grow and become more dense.”

More than two-thirds of the Netherlands is prone to flooding, and much of it is below sea-level, which gives its architects and engineers an unusual perspective on man’s relationship to water. While he stops short of proposing giant cities at sea, Olthuis thinks the definition of a city should be changing constantly.

Waterstudio.NL’s City Apps project tackles urban density and climate change. It was inspired by Olthuis’ belief that cities should be more flexible, and approached as a product.

“Smartphones all look the same but they are not, they are personalised with different apps,” he says. “We looked at cities and saw they have their own problems, and our floating City Apps simply add to the hardware of a city.”

Waterstudio’s first project is for the watery Korail slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, where 70,000 people struggle to survive. Its solution – a small floating platform housing a school with 20 iPads fixed to the walls, intended to be used as an internet hub at night – has mostly been built in the Netherlands.

“In slums there are no rules – if you build a house it can be destroyed in a few months by the government rethinking that area, but if that happens then City Apps can be moved,” says Olthuis. “We’ve put the floating platform in Dhaka. We need 14,000 plastic PET bottles to keep one City App floating, so we got the local people to collect the bottles and paid them four to six cents each.”

The next City App – this time for sanitation – is planned for Bangkok.

A similar project comes from NLE, another Netherlands-based architectural practice, which has been working with the floating community of Makoko, near Lagos in Nigeria.

Around 100,000 people are thought to live here in stilt houses – largely as a result of massive urban sprawl – but the community lacks schools and infrastructure. NLE’s solution is a pyramid-shaped primary floating school built from local bamboo, which is intended as a community hub.

Such socially progressive projects are often spin-offs of lucrative contracts elsewhere. Waterstudio’s Five Lagoons Project, a joint-venture between Dutch Docklands and the government of the Maldives, will see an area of about 740 hectares supplied with luxury floating developments.

“We are going to develop five lagoons with different functions, including a resort, a conference hotel and a floating golf course,” says Olthuis, though the point of the star item – a luxury Ocean Flower resort of 185 villas – isn’t just to tempt tourists.

“By doing this we will learn how to make big green islands, and see how we can then make social housing on the water for local people,” says Olthuis.

His long-term goal is to help the 110,000 people in the Maldives’ capital city Malé, which is barely 1.5 metres above sea level and likely to be submerged in the next 85 years.

“You need this kind of expensive project to fund the future projects to help society,” Olthuis says.

Next up is Miami, where 17 floating developments will be built on a large lake. Floating communities aren’t always a response to rising sea levels in coastal communities. Non-profit organisation the Seasteading Institute wants to initiate an autonomous offshore community that pushes total freedom and encourages innovation and experimentation beyond the reach of governments.

“We’re looking for trailblazers,” says the organisation’s promotional video. “We believe humanity needs a new, blue frontier where we’re all free to explore new ways of living together.”

It claims “seasteaders” would only need the kind of money required to live in a big city. The institute is now attempting to raise money for its Floating City project on crowd-sourcing website Indiegogo, and doing fairly well – though it also needs a “host” country.

There’s a similar issue over at Freedom Ship International, a Florida-based company that is hoping to raise the US$11 billion needed to build the world’s largest vessel.

Designed as a mobile floating platform stretching over 1,600 metres, Freedom Ship – which could set sail renamed as the Global Friend Ship – is designed to host an entire city of up to 100,000.

Just under half that number will reside permanently on the ship, which will make its way slowly around the world’s coastal regions over three years.

As it moves, a fleet of ferries and small aircraft (there’s an airport on the roof) will take residents to shore – as tourists or businesspeople – and bring tourists onboard to visit the 2.7-million-tonne vessel’s casinos, restaurants and businesses. It will have schools, a hospital and a security force.

“It’s the first ever floating city,” says Roger Gooch, director and vice-president of Freedom Ship International, “but it’s too large to go into a port so it will also stay around 15 miles [24 kilometres] offshore in international waters.”

Freedom Ship is designed to let people get away from the normal restrictions of global geography and governments, he says.

There’s a similar reason behind another offshore entity called Blueseed. A purpose-built floating platform registered in the Bahamas but moored in international waters 22 kilometres from the shores of San Francisco, Blueseed is aimed at international entrepreneurs who can’t enter the US (Silicon Valley, in particular) to start companies because of restrictive visa issues.

Offering its occupants – all with a US business or travel visa – daily 30-minute ferry rides to the mainland as well as helicopter trips, Blueseed will begin life next year on a refitted cruise ship, progressing to the custom-built Blueseed Two floating city soon after.

But life at sea isn’t just restricted to land-based humans. Olthuis has a vision of a Sea Tree, a multi-storey floating structure similar to an oil rig that could be placed in rivers, lakes and oceans near densely populated cities.

“Instead of creating green areas in the city, make them on the water,” he says. “When nature starts to colonise a Sea Tree then birds, animals and insects will use it, too.”

Olthuis already has a way to pay for it. “I could see oil companies donating Sea Trees to cities in return for drilling rights,” he says.

A Sea Tree in Victoria Harbour? That really would give Hong Kong a new look.

From sustainability to sustainaquality

Marina World, March 2013

Nestled in the Indian Ocean between Minicoy Island and the Chagos Archipelago, the Maldives comprise a chain of 26 atolls made up of islands and reefs. Tropical weather, white sand and clear water make the islands a popular holiday destination and a haven for divers but, while the surrounding ocean teems with life, home to coral reefs, eels, sharks, turtles, dolphins, manta rays and over 1,100 other species of fish, rising sea levels pose serious threat. Charlotte Niemiec reports on an ambitious community and tourism project aimed at keeping the Maldives afloat.

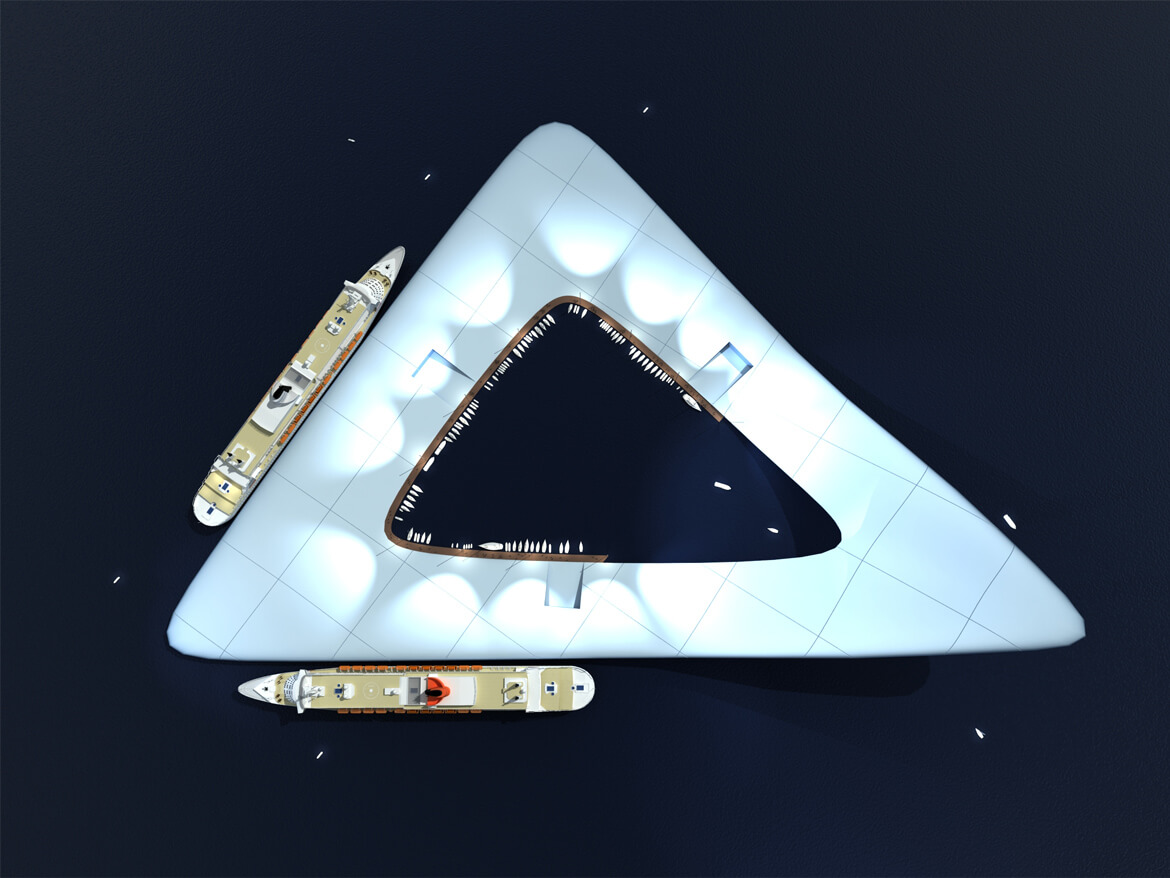

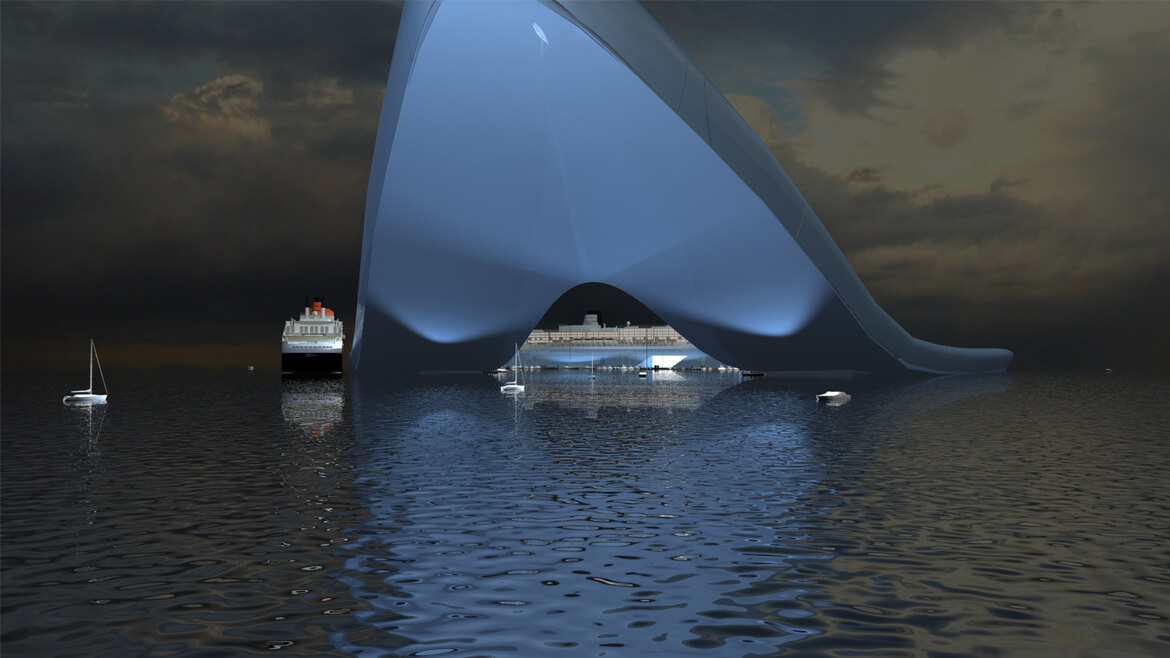

The average ground level in the Maldives is just 1.5m and the island’s president, Mohammed Nasheed, has warned that even a ‘small rise’ in sea levels would eradicate large parts of the area. Envisioning a future for its people of “climate refugees living in tents for decades” the Maldivian Government has teamed up with Netherlands- based company Dutch Docklands International in a Joint Venture Project to build a solution to the problem in the form of man-made floating islands. The ‘5 Lagoons Project’ will provide housing, entertainment and guest complexes for visitors to the Maldives, expanding its footprint and further bolstering the area’s tourist economy.

A star-shaped hotel and conference centre – the ‘Green Star’ – symbolises the Maldives route to combat climate change. Its many five- star facilities will include pools, beaches and restaurants. A ‘plug and play’ system allows for each leg of the star to be removed for easy refurbishment and a temporary one floated in and placed in position. It is hoped the centre will play host to international conferences on sea level rise, climate change and environmental issues. It is scheduled to open in 2015.

Across the water, relaxation is to be found at an 18-hole floating golf course. With panoramic ocean views, golfers can enjoy the driving range, short games practice areas, putting greens and a 9 hole par 3 Academy course. A separate area on the island provides romantic homes and townhouses in Venetian style, in a village offering boutiques, ice cream parlours, restaurants, bars and ultra- luxury palatial style villas. Movement around the island – assembled in archipelago form – is via bridges or glass tunnels in the ocean, which give guests the opportunity to enjoy the area’s sea life up close. A marina of international standard will also be built on this island.

Amillarah – the Maldivian word for private island – will consist of 43 floating islands offering luxury $10 million villas for sale to the public. Facilities will include a private beach, pool and green area, private jetty and small pavilion on a purpose-built island (the shape of which the buyer can design in advance), situated in the centre of an exclusive, large private water plot just a short swim away from the coral reefs. For those who baulk at the price tag, a separate development, the ‘Ocean Flower’ offers less expensive housing starting at $1 million. The Ocean Flower is located upmarket in the North Male atoll, 20 minutes by boat from the capital and airport, and will offer villas on three different scales. All have private pools and terraces and are fully furnished, while shared facilities include a beach, shops, restaurants, a diving centre, spa, swimming pools and easy access to the surrounding private islands. The Ocean Flower will open mid-2014, with construction beginning soon. Finally, the White Lagoon project consists of four individual ring-shaped floating islands each with 72 water villas connected. The rings function as beach-boulevards with white sand and greenery. A marina will be built inside the rings and a variety of restaurants, bars, shops and boutiques will be available.

Dutch Docklands is the master developer of the project and it controls the design, engineering, financing, construction and sales. It has appointed Waterstudio.nl as its architectural firm. Dutch Docklands CEO, Paul van de Camp, is excited about the project, viewing it as the beginning of large- scale floating projects in the area. He believes that if the project is successful, it will have proved the ability of the Maldives to combine the preservation of vulnerable marine life while expanding land for the reinforcement of tourism and urban developments at the same time. The project is an equally important one for the company and will be used as a benchmark business model for concepts around the globe. The joint venture with the Maldivian Government, which brings the needs and demands of the nation together with the commercial aspirations of Dutch Docklands is, van de Camp says, a very solid and long- lasting basis for such a big project.

Understandably, there are significant challenges to be faced when building on water. The biggest, van de Camp explains, is logistics: “We build most of the floating structure off-site, in a production yard outside the Maldives, and larger parts in the shipyards around the Indian Ocean and in the Netherlands. To get all the floating products there at the right moment (‘just-in-time’ management) at the final location ready for assembling is a pretty tough task.”

However, building on the ocean also has distinct advantages over building on land, as Dutch Docklands’ co- founder Koen Olthuis explained last year at the UP Experience Conference in Houston, USA. In the open ocean, tsunami waves are mere ripples beneath a structure that floats; water is the perfect shock absorber to seismic waves; and concerns over sea-level rise are eliminated when your home rises with it.

The islands will be constructed using patented technologies, which include the use of very lightweight Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) components and strong concrete structures. In line with Dutch Docklands’ focus on ‘scarless developments’, the materials used are environmentally-friendly, causing hardly any impact to marine life. Paul van de Camp emphasises that any possible impact on the environment is noticed upfront, while the design is on the drawing board. Using the expertise of marine specialists, marine engineers and environmental consultants, the design is adjusted at the first sign of negative impact.

At a cost of over $1 billion and funded by private shareholders, the developments are luxury resorts, catering for the more elite visitor. But van de Camp explains that the 5 Lagoons Project aims to provide a whole range of resort and business activities from reasonably-priced to ultra-luxurious. The Green Star hotel will provide the best-priced rooms, with the floating palaces in the golf course at the top end of the market.

With headquarters in The Netherlands, Dutch Docklands has a long and varied history with water. Its home country has battled against water for centuries – 20% of the country lies below sea level and water is controlled using dikes and canals. Koen Olthuis has a vision of the future in which we do not fight water but live with it and upon it. A man inspired by out-of-the- box inventions such as the elevator, which allowed cities to build up rather than span out horizontally, Olthuis sees water as another platform on which to build. It is his belief that, as so many of the world’s cities lie close to water, we should utilise this space and not just defer to the argument that there is no more space. Paul van de Camp shares this vision of a future in which floating developments are commonplace, creating new space and saving threatened ocean nations.

Schwimmende Holländer

Drinnen & Draußen,Nadine Oberbuber, October 2013

Weil die Niederlande viele Einwohner, aber wenig Platz haben, bauen sie einfach ins Wasser. Und fluten dafür sogar ihre Polder. So lernen Hausbesitzer das Schwimmen.

Natürlich kann man es verrückt nennen, was die Holländer tun. Eigentlich dürfte es einen großen Teil ihres Landes nämlich gar nicht geben. Dass Gegenden wie Westland trotzdem existieren und viele Menschen dort wohnen, das verdanken sie Pumpanlagen, die das Land trockenlegen. Zuerst bauten die Holländer Windmühlen, später gigantische Pumpwerke. Die befördern das Wasser, das von unten in die Polder drückt, über den Deich nach draußen in die See. Das ist verrückt. Aber nun sollen viele Pumpen abgestellt werden und die Polder voll mit Wasser laufen. Warum? Damit dort noch mehr Menschen wohnen können. Denn Holland hat ziemlich viele Einwohner, aber nur sehr wenig Platz und baut künftig seine Häuser aufs Wasser.

Einer, der vormacht, wie das geht, ist Architekt Koen Olthuis. Er hat sich international als Wasserarchitekt einen Namen gemacht und seine Idee von der schwimmenden Stadt auf den gefluteten Poldern schon vielen Ungläubigen erklärt. „Ihr verrückten Holländer, hört man die Menschen geradezu denken“, sagt er manchmal amüsiert, „es kostet stets eine Menge Mühe, ihnen zu erklären, dass es sehr logisch ist, was wir hier tun.“ Denn es ist nun einmal so, dass mehr als 16 Millionen Einwohner in diesem Land leben, das nicht einmal so groß ist wie Niedersachsen, aber dreimal so dicht besiedelt.

Ein Fünftel der Landesfläche vom Wasser bedeckt

Kaum irgendwo auf der Welt quetschen sich so viele Menschen auf engsten Raum wie in den Niederlanden, 400 Einwohner je Quadratkilometer. Wir Deutschen kommen nur auf 231. Doch während es bei uns dünnbesiedelte Landstriche gibt mit Wiesen und Wäldern, gibt es in denjenigen Teilen Hollands, in denen wenige Menschen wohnen, vor allem eins: Wasser.

Rund ein Fünftel der Landesfläche ist vom Wasser bedeckt, etwa vom Binnensee IJusselmeer. Flevoland, die Provinz südlich davon, existiert nur, weil die Holländer diese Polderregion dem Meer abgetrotzt haben. Gut ein Viertel der Niederlande liegt unterhalb des Meeresspiegels – dummerweise genau die Fläche, in der über 60 Prozent der Bevölkerung wohnen, im Städteknubbel zwischen Amsterdam, Rotterdam und Den Haag, die langsam aus allen Straßen und Grachten platzen. Die Region würde sofort voll Wasser laufen, wenn die Pumpen stillstehen, das nächste große Hochwasser kommt oder der Meeresspiegel wegen der Klimaerwärmung steigt. Dann bliebe bloß ein schmaler Rand entlang der deutschen Grenze übrig, der noch aus dem Wasser schaute. So weit das Katastrophenszenario.

Damit es nicht dazu kommt, haben die Holländer insgesamt 3000 Kilometer schützenden Deich aufgetürmt, die das Land dauerhaft trocken halten sollen. Selbst wenn sich der Meeresspiegel um bis zu 1,3 Meter heben würde, wie Klimaforscher bis 2100 prophezeien, schwappte das Wasser kaum über alle Deiche. Aber sie zu erhöhen wäre immens teuer. Deswegen findet Olthuis: Die Holländer hätten schon immer eine Hassliebe zum Wasser gehabt, es sei nun an der Zeit, sich mit ihm zu versöhnen. Er will, dass seine Landleute das Wasser weniger fürchten, sondern es besiedeln. Sie könnten Wasserstraßen bevölkern, weite Hafenflächen in den überfüllten Großstädten oder das IJsselmeer. Demnächst wohnen sie in Amphibienhäusern und schwimmenden Siedlungen, und wenn das Wasser steigt, hebt es die Häuser einfach um ein paar Meter an.