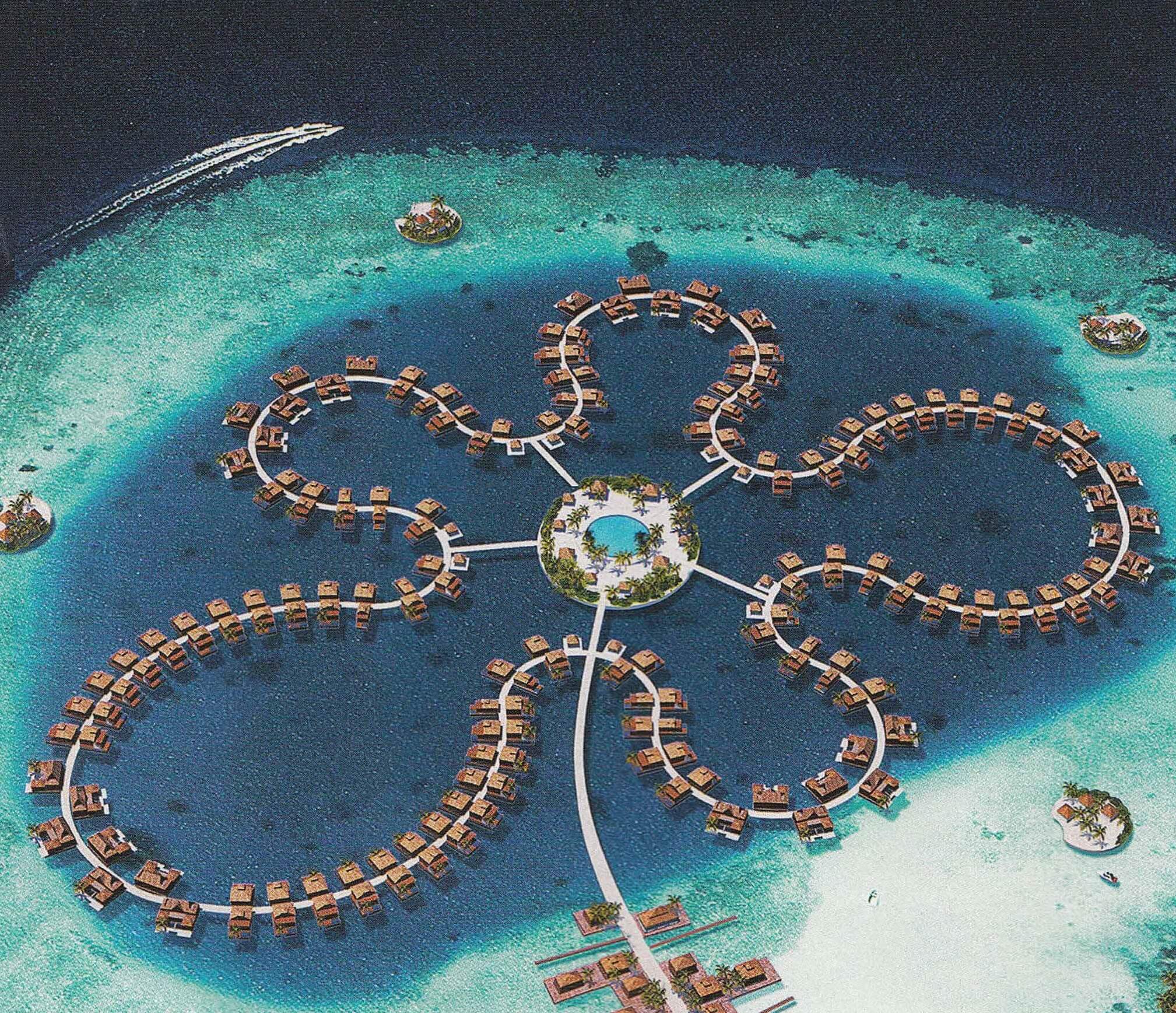

Floating Apartments Planned for The Netherlands: A ‘Viable Option’ for Boston

BostInno, Nate Boroyan, October 2013

A while back, BostInno told you that a floating Boston Harbor neighborhood next to Charlestown was being pitched to the Mayor’s office; a vision soon to be realized… in the Netherlands.

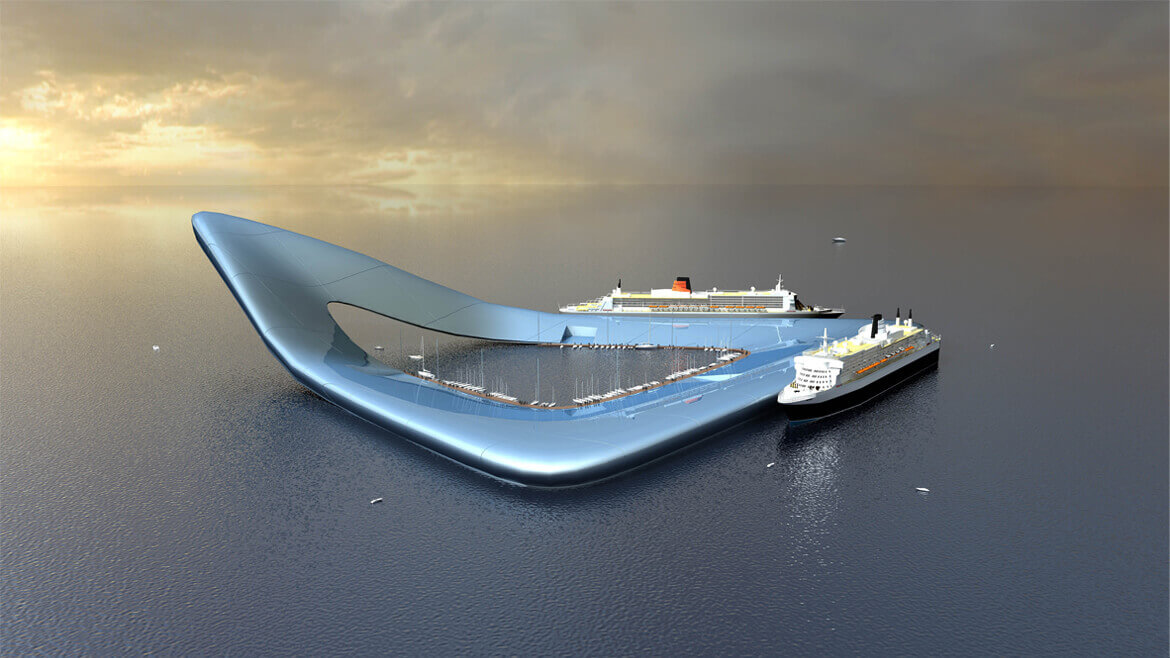

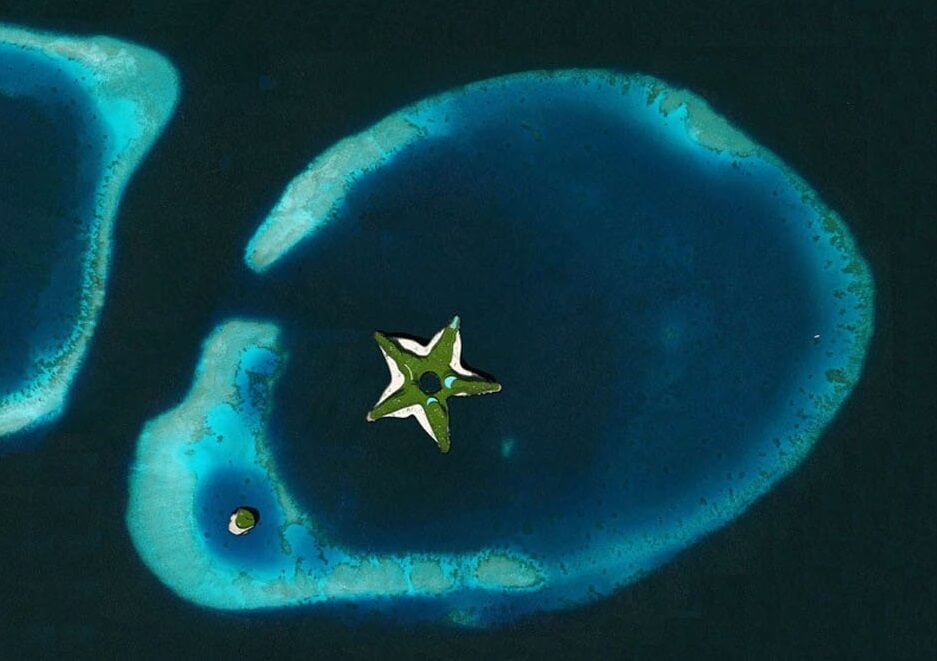

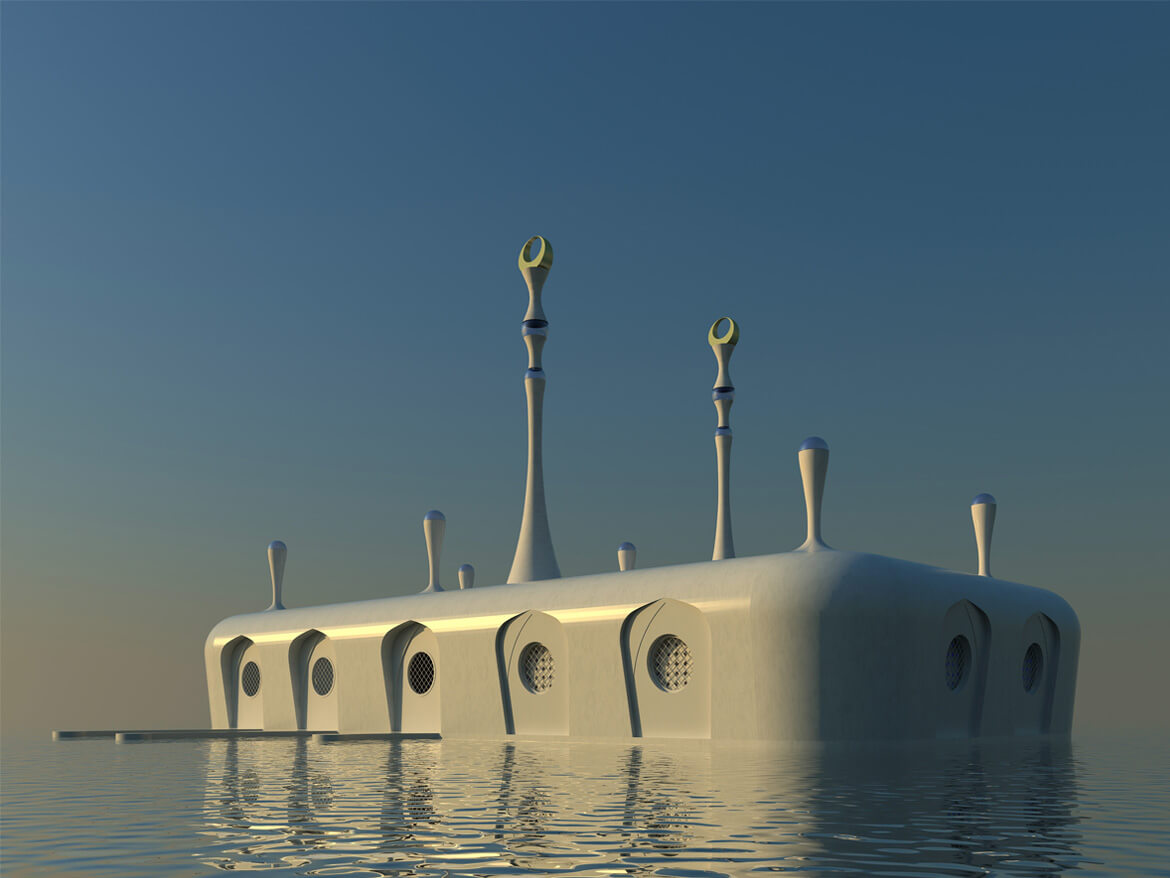

The Citadel, a luxury residential development by Waterstudio NL, is set to bring 60 stacked floating apartments to a patch of “low-lying land” that is kept artificially water-free by constant pumping. Construction could begin as early as 2014.

A report by the Harvard University Center for Environment previously stated, “Without action … rising seas will sooner or later alter most of civilization’s urban footprint,” suggesting that there might actually be a need for – rather than just creative inspiration to build – floating residences.

The HU report included information from a Graduate School of Design thesis by Michael Wilson (’07) suggesting a scenario where the sea-level could rise 6.6 feet, combined with a 100-year storm surge of 18 feet that would “reduce Boston… to a series of drumlins.”

Even a modest rise in sea level of 12 inches – expected by 2046 or sooner – in cahoots with a powerful storm, high tides and optimal winds, “would make Boston briefly part of the Atlantic Ocean,” the report added.

So. Not great. But innovative designs like the Citadel could help combat this terrifying prospect. Just ask the Dutch.

To be built on top of a floating concrete structure, the Citadel will provide residents of the Netherlands “easy” access to land and will include a car park. Made up of 180 modular components, the development will be built around a central courtyard, all of which sits atop six feet of water, which could rise to 12 feet.

Naturally, a portion of owners will have space designated to dock their boats.

There are 3,500 “polders” — chunks of low-lying land protected by dykes — in the Netherlands, so this development trend has the potential to go mainstream. Reportedly, 1,200 additional residential units are expected in the future.

Because floating apartments aren’t cool enough, units will also be energy efficient and feature green roofs for sustainability, not just additional awesome-points — but kind of.

With Boston, like the Netherlands, being among the world’s major port cities that could face a dramatic environmental crisis, urban developers and planners might need to develop a larger prevention plan.

But for now, let’s stick to wicked freakin’ sick floating homes, dood. (See above)

Yes, similar floating abodes like the Citadel have been discussed for Boston. Before any could become reality, however, there are a number of infrastructure issues that need to be dealt with, says Vivien Li, president of the Boston Harbor Association, during a phone call with BostInno.

Infrastructure concerns, such as waste and sewage management needs, and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act are not insurmountable; a ramp that adjusts to the floating tide, for example, would have to be built to allow disabled residents access to any floating development.

The bigger issues, Li said, are strict permitting regulations and residential financing.

Currently, developers are pushing for construction of new high-end apartments rather than luxury condominiums – reportedly more realistic for floating developments.

Financing for luxury condos, however, remains a bit less realistic. “Banks just are not financing condos right now,” Li said.

With Mayor Menino’s administration requiring 15-20 percent of residential developments units be “affordable,” areas such as the city’s Waterfront are booming with luxury apartments rather than condos, many of which, Li said, remain unaffordable for many.

A vote of confidence from Boston’s next mayor for floating residential developments could be a way for either candidate to “put a mark or a brand on his administration,” said Li, suggesting that either Walsh or Connolly could choose to take a creative approach when it comes to the affordable housing issue.

But…“Theory has to be translated into practice,” said Li. Despite a wealth of resources, thanks in large part to our myriad colleges and universities, this has yet to happen.

Thus far, only one floating development, suggested by Ed Nardi, the president of Cresset Development, has been discussed for the Boston Harbor near Charlestown. But that never gained traction, Li said.

High construction costs coupled with legal fees dished out to navigate zoning permits, Li said, would make a future floating neighborhood very, very, pricey — exclusive to Boston’s elites.

The silver lining is that an on-water development is doable, especially in the Boston Harbor.

Julie Wormser, TBHA’s executive director, called a Boston Harbor development a “viable option,” during a phone conversation with BostInno.

Even if another Hurricane Sandy or Nemo makes its way to the Boston coastline – and one will, eventually – the harbor is uniquely protected.

When Sandy struck, some coastal areas in the state saw 25-foot waves, Wormser said, adding the Boston Harbor didn’t see waves nearly that intense.

The harbor’s bowl shape and 34 islands requires hurricanes to travel on a “very particular path” in order to cause damage to the inner harbor, Wormser said. Hull’s Nantasket Beach and Deer Island are typically hit first, serving as Boston’s front lines.

Feasible? You bet. A popular idea? Wormser says, yes. Many others in the wake of Nardi’s Floatyard idea said differently. Will Boston have a floating development like the Citadel soon? Not likely.

After Menino takes his final bow, however, Connolly or Walsh could have something to say about that.

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS

TRACY METZ, AMSTERDAM FRAMER, AND KOEN OLTHUIS