Grüne Stadterweiterung auf Wasser

By Elisabeth Schneyder

UBM Magazin

2020.Oct.01

In immer dichteren Städten bleiben Flora und Fauna auf der Strecke. Das Büro Waterstudio will das Dilemma mit dem „Sea Tree“ lösen: Naturreservate auf schwimmenden Türmen sollen für grüne Stadterweiterung sorgen. Für Menschen unzugänglich – aber im Dienste ihrer Gesundheit und Zukunft.

Zutritt verboten, Nutzen garantiert

Die Idee zu „Sea Tree“ steht schon seit Längerem auf Waterstudios Agenda. Ähnlich wie futuristische Pläne des visionären Architekten Vincent Callebaut oder seines italienischen Kollegen Luca Curci, harrt sie jedoch der Umsetzung. Genau wie viele andere, spannende Konzepte für mehr urbanes Grün und Umweltschutz, von denen sich „Sea Tree“ allerdings in einem zentralen Punkt unterscheidet: Den Entwicklern geht es nicht um neue Erholungszonen für geplagte Städter. Der gestapelte „Meeresbaum“ soll für Menschen sogar unzugänglich sein. Er soll schwimmende Naturreservate schaffen. Im Namen von Biodiversität und Umweltschutz. Weil beides Gesundheit und Zukunft aller Lebewesen dieses Planeten dient.

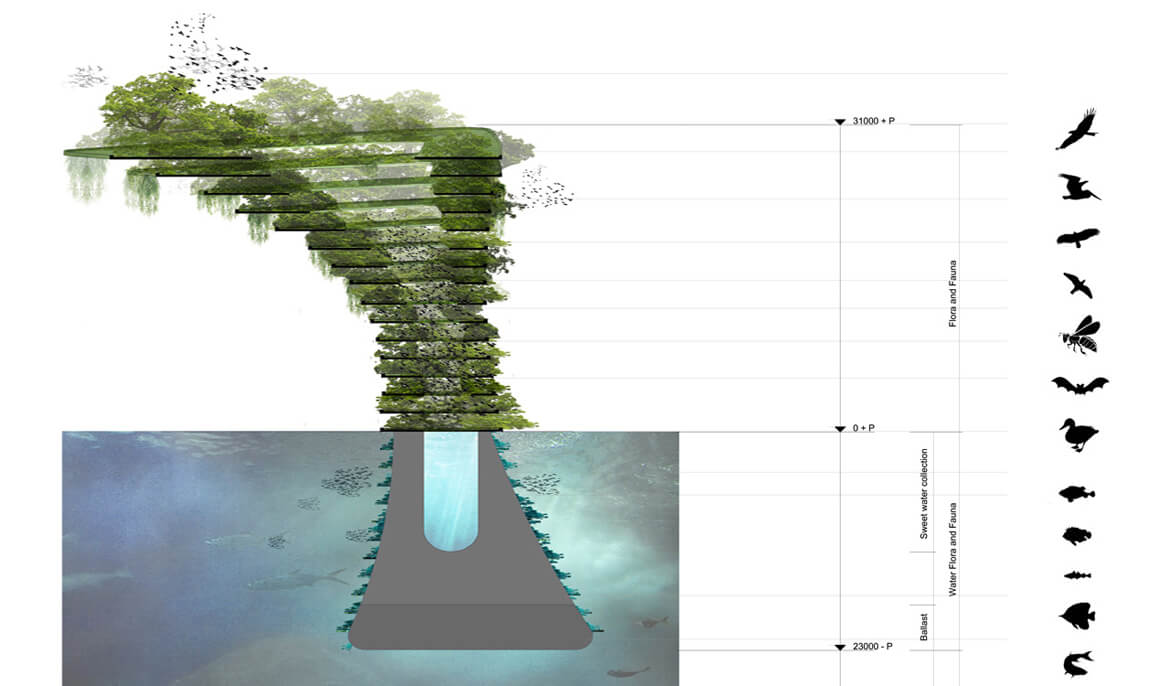

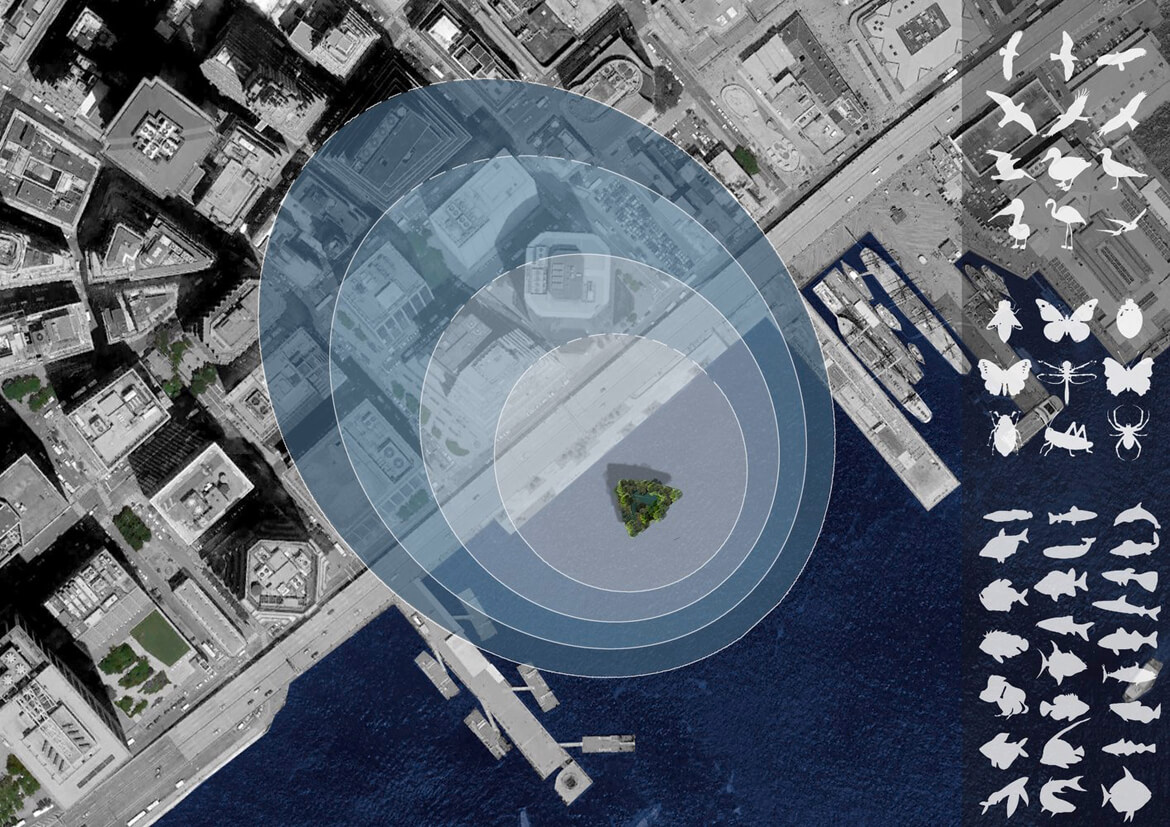

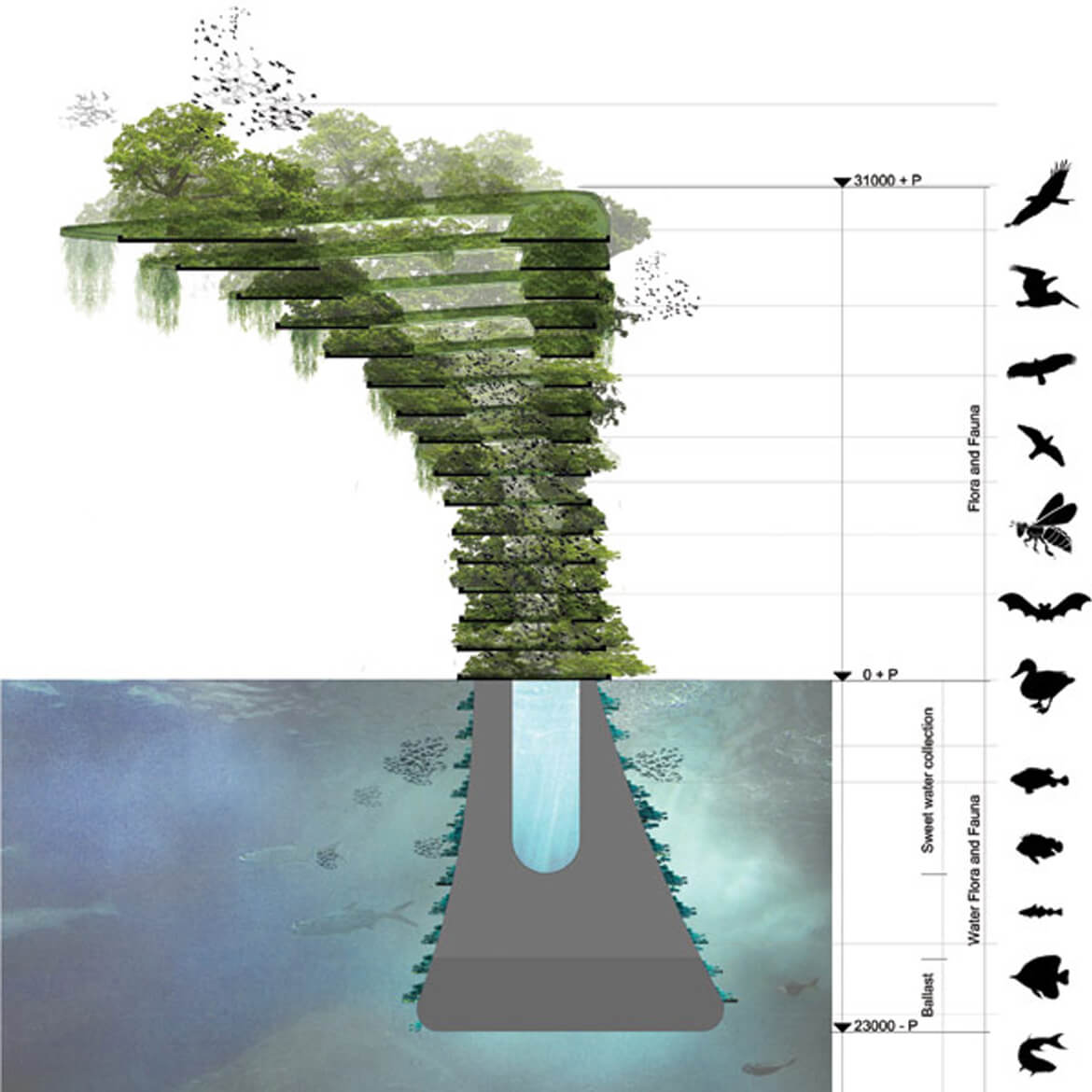

Als eine Art „City App“ soll der „Meeresbaum“ in Häfen, an Fluss-, Ozean- und Seeufern, vor Inseln, aber auch nahe an Industriezonen auf freiem Wasser ruhen. Als schwimmendes Objekt, das zu 100 Prozent für Flora und Fauna gebaut und konzipiert ist. Die grüne Stadterweiterung kann in Höhe und Tiefe dem jeweiligen Standort angepasst werden. Denn die Konstruktion berücksichtigt Bedingungen wie Wassertiefe, Wellen, Gezeiten und Strömungen. Wie ein Baum im Wald, soll sich der „Sea Tree“ sanft mit dem Wind bewegen. Halt findet der Turm durch ein am Meeres-, Fluss- oder See-Boden befestigtes Kabel- und Verankerungssystem.

Öl-Türme für Umweltschutz

Das Gerüst des vielschichtigen Turms ist aus Stahl. Und es wird, so Waterstudio, unter Verwendung neuester Offshore-Technologie gebaut. „Sea Tree“ nützt von Öllagertürmen im offenen Meer erprobte Technik: „Die Ölgesellschaften haben diese schwimmenden Lagertürme seit Jahren benutzt. Wir haben ihnen nur eine neue Form und Funktion gegeben“.

Und geht es nach den kreativen Architekten, kommen Ölkonzerne auch auf ganz andere Art ins Spiel: Sie sollen beweisen, dass sie bereit sind, zum Schutz der Umwelt beizutragen. Schließlich verfügten sie sowohl über hilfreiches Wissen, als auch über passende Ressourcen. Anders gesagt: Her mit den Türmen – aber künftig ohne Öl.

Entsprechend heißt es in der Projektbeschreibung des Waterstudio-Teams: „Sea Tree bietet den Ölgesellschaften eine Möglichkeit, ihre positive Einstellung gegenüber der Umwelt umzusetzen“. Das „schwimmende Produkt“ könne Städten hinzugefügt werden wie eine App einem Smartphone: „Der Ölkonzern bleibt Eigentümer und die Stadt stellt einen Standort zur Verfügung“.

Was für die Unternehmen vermutlich feine Image-Pflege wäre, würde Umwelt und Allgemeinheit tatsächlich nützen. Vor allem, wenn es nicht bei einem einzigen „Meeresbaum“ bleibt. Denn dass die grüne Stadterweiterung Biodiversität fördern, die Luft in Ballungsräumen verbessern und dem Klimawandel entgegenwirken könnte, liegt auf der Hand.

Immerhin spielt langfristig ungestört gedeihende Vegetation eine gewichtige Rolle bei der Absorption von CO2 aus der Atmosphäre. Und da, wo „Wildnis“ keinen Platz mehr hat, bemüht man sich, auf „kultivierte“ Art vom Mehr an Grün zu profitieren. Nicht umsonst setzen Architekturbüros und Stadtplaner in aller Welt zusehends auf dicht begrünte Fassaden, Dächer und Gebäude. Projekte wie der „Mandragora-Wohnturm“ für New York, der Düsseldorfer „Kö-Bogen 2“ oder Koichi Takadas riesiger „Urban Forest“ in Australien sind nur ein kleiner Auszug aus der aktuellen Beispielliste.

Umdenken gefragt

Bedenkt man, dass Erdölkonzerne selbst zu den größten CO2-Produzenten der globalen Wirtschaft zählen, klingt Waterstudios „Sea Tree“-Vorschlag noch recht kühn. Allerdings könnte das Projekt mittlerweile doch mehr Gehör finden. Schließlich betonen inzwischen auch Unternehmen wie BP, ihren Kohlendioxid-Ausstoß verringern zu wollen. Und der Druck der Öffentlichkeit, es nicht bei bloßen Ankündigungen zu belassen, wächst.

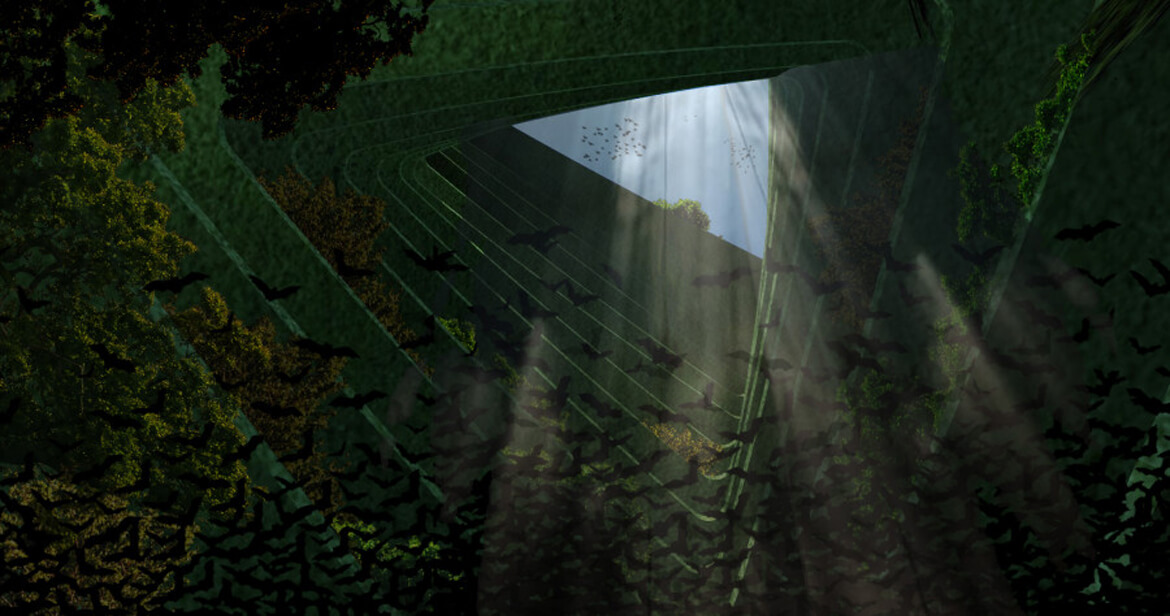

Die grüne Stadterweiterung nach Waterstudio-Modell könnte kilometerweite Zonen positiv beeinflussen. Weit über den Standort jedes „Sea Tree“ hinaus. Auf die Idee zum originellen Entwurf kamen die Architekten durch Ökologen: Gefragt war ein Konzept zur Schaffung eines ungestörten Lebensraums für Pflanzen. Für die Niederländer lag es nahe, Wasser als schützende Barriere zu nützen, die Menschen von den geplanten Oasen fernhält. So, dass etwa auch Vögel und Insekten wieder eine Heimat finden. Auch dort, wo dichte Ballungsräume keine störungsfreien Plätze mehr für Nest und Bienenstock lassen.

Neuer Lebensraum, auch unter Wasser

Inspiriert von norwegischen Öl-Lagern wurde an einer Strategie gefeilt. Auch die Kronen mächtiger Bäume standen Pate. Ebenso, wie städtische Parks: Das Team unterteilte solche Grünzonen in Abschnitte. Diese wurden im Entwurf vertikal über einander geschichtet.

Der grüne Turm soll allerdings nicht nur über der Wasseroberfläche Natur erblühen lassen. Das Konzept sieht vor, dass auch darunter Vielfalt wachsen kann: Dort soll der „Meeresbaum“ Lebensraum für kleine Wasserlebewesen schaffen. Passen die klimatischen Bedingungen, könnten dort sogar Korallenriffe entstehen.

„Wir haben Experten der renommiertesten Institute Hollands konsultiert“, versichert das Waterstudio-Team in der Beschreibung des Projekts. Der Entwurf basiere auf aktuellsten Forschungsergebnissen um optimale Bedingungen für Flora und Fauna zu bieten. Die Errichtungskosten seiner Wasser-Wolkenkratzer bezifferte Waterstudios Chef-Architekt Koen Olthuis in der Entwicklungsphase – vor wenigen Jahren – mit etwas mehr als einer Million Euro.

Sein Traum: „Sea Tree Wälder“ vor Manhattan und anderen Metropolen in Uferzonen. Überall dort, wo Raumnot kaum noch oder gar keinen Platz mehr für Naturreservate lässt, könnte die grüne Stadterweiterung auf dem Wasser für mehr Lebensqualität sorgen. Als grüner „Blickfang“ und effiziente Umweltschutz-Maßnahme.

Mehr als ein „Fantasie-Projekt“

Die ausgefallene Idee als Vision eines Fantasten abzutun, wäre zu kurz gedacht. Immerhin gilt Architekt Koen Olthuis als Spezialist für wasserbasierte Entwicklungen. Das „Time Magazine“ setzte ihn bereits einmal auf die Liste der einflussreichsten Personen der Welt. Und das französische „Terra Eco“ ehrte den Holländer schon 2011: Im Ranking der 100 „grünen“ Personen, die die Welt verändern werden.

Zudem klingt bestechend logisch, was Olthuis propagiert: „Prognosen gehen davon aus, dass bis 2050 etwa 70 Prozent der Weltbevölkerung in urbanisierten Gebieten leben werden. Die Tatsache, dass etwa 90 Prozent der größten Städte der Welt am Wasser liegen, zwingt uns, die Art, wie wir mit Wasser in der verbauten Umwelt umgehen, zu überdenken“.

„Planung für den Wandel“

Künftige Entwicklungen und Bedürfnisse sind unvorhersehbar. Deshalb sei „Planung für den Wandel“ nötig, meint der Waterstudio-Chef: „Unsere Vision ist, dass schwimmende Großprojekte in städtischer Umgebung eine greifbare Lösung bieten, die sowohl flexibel als auch nachhaltig ist“. Ideen dazu hat er viele. Zum Beispiel den „Meeresbaum“, der Tieren und Pflanzen – die schließlich auch fürs Wohl der Spezies Mensch vonnöten sind – verlorenen Lebensraum zurückgibt.

By Tanja Lina

By Tanja Lina

By Haus mit Zukunft

By Haus mit Zukunft