These Houses Have the Ultimate Water View

By Sam Lubell

The New York Times

May.24.2018

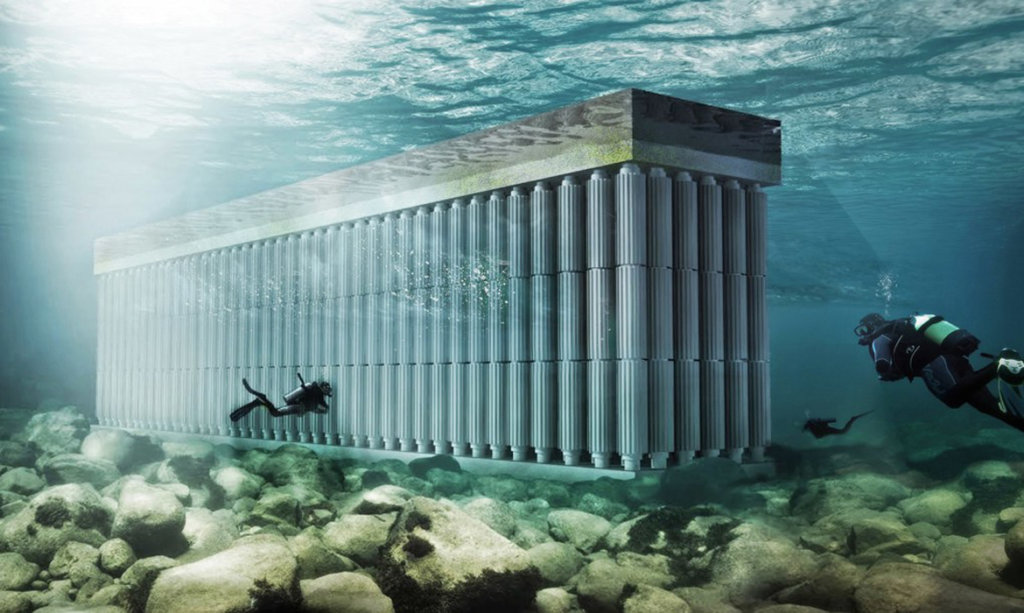

Photo credit: Credit Miquel Gonzalez

Floating villas in Dordrecht, the Netherlands, south of Rotterdam. Designed by Waterstudio.NL, the villas use heat exchange power and have extra-large foundations to create terraces and other outdoor spaces.

Few places in the world are as married to the water as Venice. Not only has the Floating City replaced streets with canals and land with islands, but its buildings also sit on wooden piles, driven into the ground deep below the water. Like much of the sea-hugging world, the city is also facing an existential threat as the waters rise and its ground sinks.

The city’s art and architecture Biennales (the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale starts on Saturday and runs through Nov. 11) have long reflected this simultaneously magical and dire condition, with exhibit after exhibit addressing sustainable architecture, climate change and rising seas.

Many have even drifted along Venice’s canals themselves, including Mike Bouchet’s (doomed) floating house; Croatia’s floating pavilion; Kunle Adeyemi’s floating school; Joana Vasconcelos’ floating artwork, Trafaria Praia; and Aldo Rossi’s floating Theater of the World.

As is so often the case, life is imitating art, and floating architecture is emerging as one of the built world’s most promising markets — for many of the reasons pinpointed at the Biennale.

“We see architects as spanning between infrastructural ideas and society,” said Yvonne Farrell, one of the Biennale’s directors, who posits that if architects can take a leading role on vital environmental issues through emerging technologies like floating buildings, then they can also help re-establish their primacy in the construction process.

“You cannot not deal with environmental issues if you’re an architect these days. It has to be an essential part of your value system,” added Shelley McNamara, who is also one of the directors. “We’re all connected. We have to find solutions where art and culture and industry can all find a way to survive.”

Architects, boat builders, developers and city planners worldwide are seizing on the opportunity as cities run out of space to build, tides continue to rise and demand for efficient construction spikes. They’re creating inventive designer homes and floating resorts, and even floating cities that can be prefabricated off site and simply floated into place.

“For many, floating is something new and adventurous,” said Max Funk, co-editor of “Rock the Boat: Boats, Cabins and Homes on the Water” (Gestalten, 2017). The book reveals an explosion of creativity in buoyant architecture, including an egg-shaped floating cabin in England, floating spas (with working saunas) in Finland and the United States, and floating geodesic domes in Slovenia.

“Having a floating home used to be something only for vacationers or the uber-wealthy,” Mr. Funk said. “Now more people are realizing they can do it. And with downsizing becoming a trend, it goes along with the idea that quality of life is more important than size.”

Claudius Schulze, whose floating art studio graces the cover of “Rock the Boat,” built his 32-foot-by-16-foot timber-sided box, coated in fiberglass resin, for about 20,000 euros (about $24,000) with the help of friends, including a structural engineer. It has state-of-the-art amenities like Wi-Fi, onboard water filtration and solar power. It has its own motor (technically making it a houseboat), and Mr. Schulze has used it in, and en route to, Amsterdam, Paris and Hamburg, Germany, mooring it in each location for about €200 a month.

“It really is the perfect studio space,” he said. “It has all the inspiration and little of the distraction.”

On Seattle’s Lake Union — which has hosted floating homes since the 1920s and now has more than 500 of them — William Donnelly has lived in a multilevel floating home designed by Vandeventer & Carlander architects for more than seven years.

“I enjoy smelling the water, hearing the water,” he said. “I love the idea that my home isn’t fixed to the land. It’s freeing.” It’s not all perfect — the lake is popular, and sometimes his tightly surrounded home feels like a fishbowl — but he said that he would never live on land again.

Thanks to such situations, and to the rise in the price of waterfront property, the market for floating architecture is growing in North America, said Allison Bethell, a real estate investor analyst at FitSmallBusiness.com. Newer homes and their slips are not cheap, but since the market is young and houses are limited in size, they are rarely as expensive as prime waterfront real estate.

Outside of Seattle, where houseboat construction is being curtailed because of the potential impact on local salmon populations, Ms. Bethell said, the most prominent areas in North America for floating homes are the San Francisco Bay Area; Vancouver, British Columbia; Key West, Fla.; and Portland, Ore.; where the number of floating homes has doubled since 2012.

The trend is also expanding rapidly in Asia and the Middle East, but it is furthest along in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands, which is mostly below sea level. Estimates report that the country now has more than 10,000 floating residents, none more densely packed than in Ijburg, a growing development of floating homes clustered off man-made islands on the eastern edge of Amsterdam.

Over 50 of these residences — featured in the 2014 U.K. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale — were designed by Marlies Rohmer Architects & Urbanists and developed by Amsterdam-based Monteflore. The simple, industrial-inspired homes, floating on concrete bases (the current norm) were fabricated in a factory and floated into place.

“Most of the world now lives in cities, and most cities are near water,” said Ton van Namen, managing director of Monteflore. He said his team was working on a floating development along the west coast of Wales, and had been approached by interested parties from China, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Dubai and Abu Dhabi of the United Arab Emirates.

Koen Olthuis, an architect from the Netherlands who founded Waterstudio.NL, one of more than a dozen European firms specializing in boutique buoyant homes, sees floating architecture as the future. He said he had built more than 150 floating residences in the last 15 years, including a group of floating villas in Dordrecht, south of Rotterdam, that use heat exchange power and have extra-large foundations to create terraces and other outdoor spaces.

Now he is increasing his repertoire as both a designer and a planning consultant for floating hotels, restaurants, stores, resorts and private islands, and even floating cities.

“Blue cities,” as he calls them, can be more flexible and eclectic, and respond faster to rapidly changing demands from society and industry.

“I’ve talked to many urban planners, and they all say the same thing — by the time a city’s plan is finished, it’s no longer in line with society.”

He has consulted with officials in Rotterdam, the Maldives, Ivory Coast and Saudi Arabia, on flood-safe construction, smoother regulations for floating architecture, and how to float needed facilities, like a harbor, into place when needed. He envisions floating museums and factories shared by nearby cities.

“Once the elevator was invented, the whole recipe for a city changed,” Mr. Olthuis said. “Now a similar thing is happening on the water.”

The transformation of the typical floating building is, like most things in Dubai, going ahead full steam — thanks in large part to the Finnish company Admares, whose chief executive, Mikael Hedberg, started as a shipbuilder and now merges land and sea-based construction technologies.

Admares in 2016 completed the Burj Al Arab Terrace, a 2.3-acre island, attached to the sail-like Burj Al Arab tower, containing pools, cabanas, sun loungers, and a restaurant and bar. It was built in a factory in Rauma, Finland, floated into place in six pieces and then driven into the seabed via piles.

Besides location, what especially draws clients, Mr. Hedberg says, is the fact that since structures can be built off-site, on-site construction time is cut way down. The Burj Al Arab Terrace was set onto piles and welded together in about three months, subverting a landfill process that can take up to three years.

And unlike construction on landfill, floating buildings and islands create minimal ecological disturbance. Often floating platforms and piles, like those at the Terrace, serve as habitats and valuable cover for marine life.

The rise of floating design — and issues related to both rising tides and sinking cities — are having a clear impact on land, where designers and officials contend with water whether they like it or not. In many ways, floating buildings serve as laboratories for our new environmental reality.

Mr. Olthuis has helped create a development in Utrecht, the Netherlands, where “amphibious” homes — sitting on buoyant concrete bases and tethered to supports — can float in the event of flooding. (The Los Angeles firm Morphosis created a similar system for its modular, foam-cored Float House in flood-prone New Orleans.) He is also developing hybrid structures that can float on the water and, through a jack system, sit on land, making them even more flexible to personal and urban change.

“Land itself is no longer fixed in the way we’ve traditionally seen,” said Kristen Hall, an urban designer at Perkins & Will, which is incorporating water-reactive solutions for its new Mission Rock development at San Francisco’s Mission Bay, like pile-supported buildings, streets and sidewalks, and flexible utilities. “The question is, how much do you plan for change and roll with the change, and how much do you try to resist the change?”