Stedenbouw, Koen Olthuis

By Marco Mulders

ZoomZoom Mazda

April.2015

Een drijvende stadswijk? Voor Koen Olthuis (1971) is het allang geen sci-fi meer. Met zijn bedrijf Waterstudio creëert hij oplossingen om op zee te leven.

By Marco Mulders

ZoomZoom Mazda

April.2015

Een drijvende stadswijk? Voor Koen Olthuis (1971) is het allang geen sci-fi meer. Met zijn bedrijf Waterstudio creëert hij oplossingen om op zee te leven.

By Christopher F. Schuetze

The New York Times

April.23.2015

Living Above and Below the Water’s Surface in Amsterdam

Floating houses built on man-made islands make up the new neighborhood of IJburg in Amsterdam. Center, the home of Monique Spierenburg and Kees Harschel, whose seven-meter sailboat is docked right next to the living room. CreditFriso Spoelstra, Boat People of Amsterdam, Lemniscaat, 2013

AMSTERDAM — When asked about his three-story floating house in a gleaming new part of Amsterdam, Kees Harschel, a 65-year-old native Amsterdammer, likes to compare his living situation to winning the lottery.

“This house fits us like a second skin,” said Mr. Harschel, a retired physical education teacher, sitting in his dining room on the ground — or in this case water-level — floor of the house he has shared with his wife, Monique Spierenburg, since the couple had it built seven years ago.

In Mr. Harschel’s case, the comparison with a game of chance is more than just pride of ownership: To become part of the community of 36 houses floating on an artificial lake on Steigereiland, one of several man-made islands that make up the burgeoning new neighborhood of IJburg, Mr. Harschel competed with more than 400 applicants.

“My wife said: Go on, gamble — you won’t win anything, so try it,” said Mr. Harschel, who lived in a house on the Amstel river before moving to IJburg. But winning a spot in the small community — which the couple did in 2007 — was just the first step in a journey that would include hiring a renowned architect and battling the bureaucratic wrangling that comes with being a building pioneer in Europe.

The result is an expression both of one couple’s love of the water and of innovative living for which the Dutch — long known for their centuries-old ornate houses — are garnering an international reputation.

IJburg, home to about 20,000 people currently, is expected to eventually house 45,000. It has been rising over the past decade on a succession of artificial islands to the southeast of the city center, conceived to ease a chronic housing shortage. The area attracts many young families and professionals who, with a newly built tram line, can be in the heart of Amsterdam in 10 minutes.

The city has taken care to create a mixed community, with mansions, social housing and both market-rate and fixed-rent apartments, all sharing courtyards, public squares, parks, shopping centers and canals.

And while the 36 houses in Mr. Harschel and Ms. Spierenburg’s part of the neighborhood are all individually designed and built, those across the lake are by a single developer. Some are rented and some are owned by their inhabitants.

The couple’s house, which is nine meters, or 30 feet, high, rises just seven and a half meters above the water surface (the submerged 1.5 meters is part of the fully functional bottom floor) and is seven meters wide and 10 meters deep. (The width of the house is set by the size of the lock connecting the IJmeer to the little lake that would become its home.) Over all, the design accommodates 175 square meters of total floor space, or 1,880 square feet, with a 35-square-meter roof terrace.

The interior is the essence of Dutch simplicity. The main floor has a kitchen and dining room, where the couple do most of their socializing. Vast windows ensure the interior is flooded with diffuse reflected light and offer views of the IJmeer and the rest of the floating neighborhood.

The top floor is divided between an indoor living room and an outdoor patio. When the doors are open in the summer, the space becomes one, evoking architecture from much warmer climates.

Built to suit the couple, the basement includes two bedrooms, a master bathroom, an infrared sauna, a study and, according to Mr. Harschel, one of the most important rooms in the house: a two-and-a-half-square-meter woodworking and repair shop.

Although the house feels like a normal house, it is actually floating on its concrete basement foundation. (Power, water and other services are supplied via the fixed dock, which also acts as the land access, installed and maintained by the city.) Eye-level windows in the basement afford just-over-surface views.

Its unusual construction allowed the house to be built miles away from where it now floats, and if Amsterdam’s building code did not forbid it, the owners could simply take it with them when they moved.

“I’m a sailor,” said Mr. Harschel, who pilots saloon boats — canal boats often used for private day trips — around Amsterdam. His seven-meter Thalamus Working Boat is docked right next to the living room.

“On summer evenings we can just take some beer, wine and toast and have dinner out on the water,” said Mr. Harschel, who last summer sailed to the south of England, departing from and returning to the side of his house.

On the rare occasion when the lake freezes over, Ms. Spierenburg straps on her speed skates and takes to the ice without having to leave her house to reach the rink.

“It is much more a gateway to freedom than it is just a place to live,” said Koen Olthuis, who designed this house and whose architectural office, Waterstudio, specializes in designing floating buildings all over the world. “Skating around the house, swimming around your house — it’s marvelous.”

Both owner and architect concede that being one of the first houses on the pier came with costs.

“They paid a bit for the things we learned,” said Mr. Olthuis, explaining that the pioneering families did pay — in money, time and frustration — for what the city was learning about urban planning on water.

“It was a book this thick, but we were free,” joked Mr. Harschel, waving an imaginary building code volume.

Mr. Olthuis noted that the house had been built following code for land houses, which, in keeping with a mandate to build greener houses in the Netherlands, stipulated triple-glazed windows, heavy insulation and even a heat exchanger to retain heat from effluent — something that most houseboats, which tend to be light houses on a heavy foundation, avoid.

Mr. Harschel estimates that the couple spent 350,000 euros, or $380,000, to build the house (the lease for the lot is €600 a month), and guesses that the value of the property has probably more than doubled in the years since it was built.

“These people living here are pioneers; they are willing to take a risk, they are willing to try stuff out,” said Mr. Olthuis. “They all have a very strong feeling of freedom. That’s why they came here.”

By Paul van Deelen

Bouwen met staal

April.2015

Een opdrachtgever met een ruim budget, een mooi ruim kavel en een gevelmateriaal met ruime toepassingsmogelijkheden. Architect Koen Olthuis benut zijn ruimte om een uitgesproken ontwerp te maken met bijna industriële precisie. de transparante gevels en gekromde gevelvlakken zijn het best te maken met een stalen drager.

By Business Spotlight

March.2015

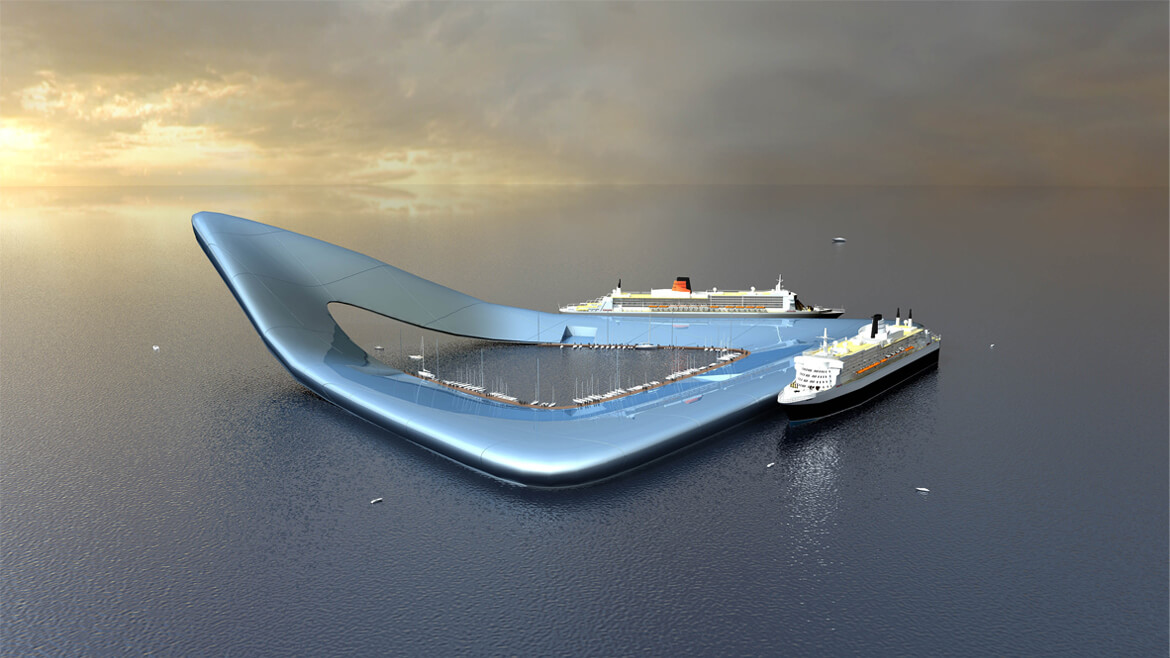

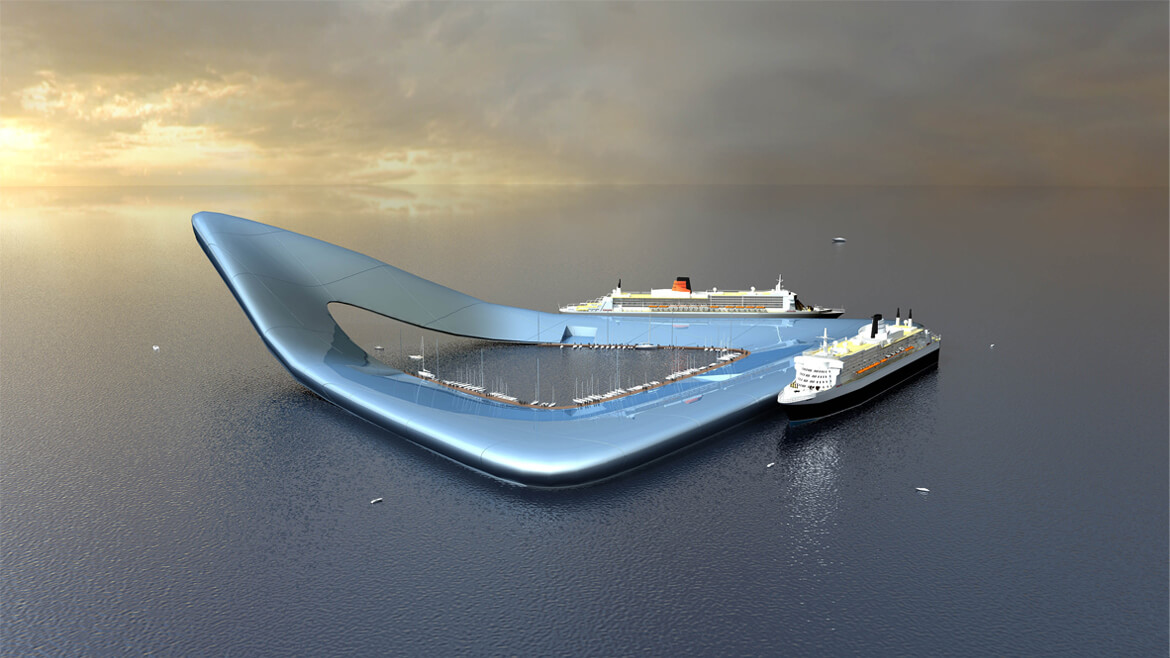

Photo credit Waterstudio

Recently, Dutch firms have carried their control over the sea one step further, pioneering floating buildings and cities as a solution to rising sea levels. One of them is the developer Dutch Docklands, which describes itself as having ‘learned to live with the water instead of fighting it’. it works closely with the firm of architects Waterstudio, run by awardwinning architect Koen Olthuis.

“The climate change generation is no longer interested in iconic architecture, but are looking for iconic solution,” says Olthuis. “It is not the result of the individual architect that that counts, but the effect on society.” Perhaps their most futuristic work is the Krystall hotel, which will open at the end of 2016. Designed to look like a giant floating snowflake, it is being built in the icy seas near the city TromsØ in Norway. The Hotel will have glass roofs so guests can watch the Northern Lights. Its hallways will be lined with futuristic blue shapes and fireplaces will be converted in transparent blocks to look like ice.

“We call it scarless development. If you take it away after 100 years or so, it will not leave any physical foot-print,” explains Olthuis, who says that Dutch attitude is: where there is nothing, anything is possible. “The Dutch created Holland out of the sea, and that mentality is in our DNA, forcing us to be creative in situation where there seem to be no obvious solution. Some of the innovations that were born of necessity soon show potential for worldwide use.”

By Inhale MAG

Filled under: Architecture, front page

March.2015

Photo Credits Waterstudio.nl

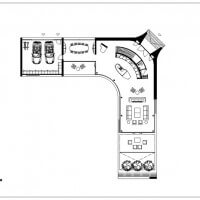

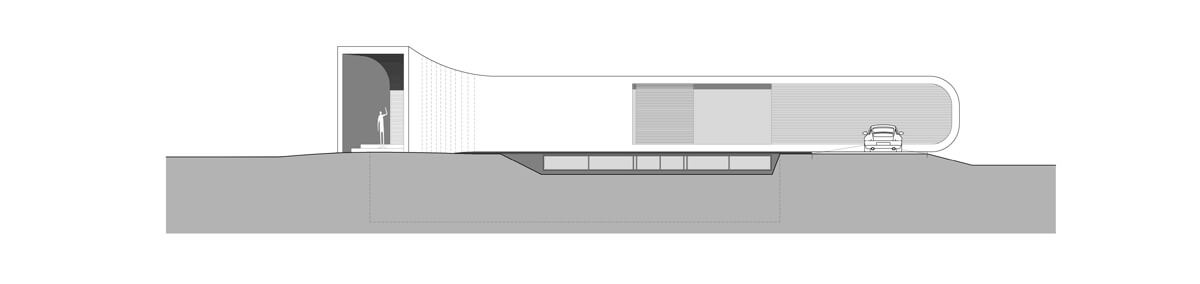

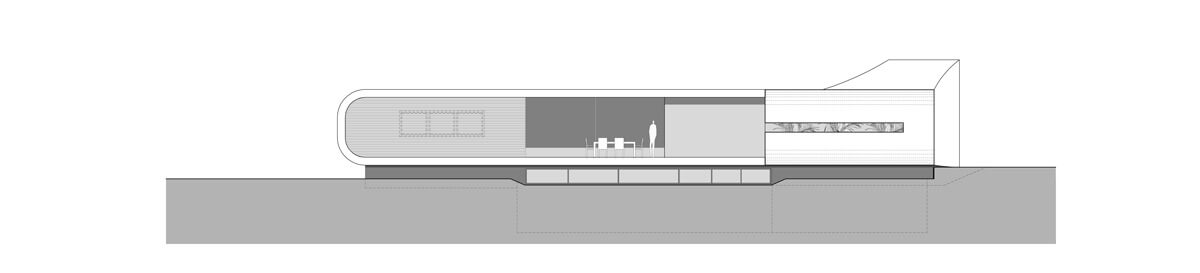

From the very first moment of seeing the planned location for this villa Architect Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio set out to design a subtle villa that would allow for the optimal experience of its surroundings.

In order to maintain the rural character of the location, the assignment came with strict regulations limiting the volume allowed above the ground level. These limitation eventually proved to give rise to a rather sophisticated design filled with spatial solutions.

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

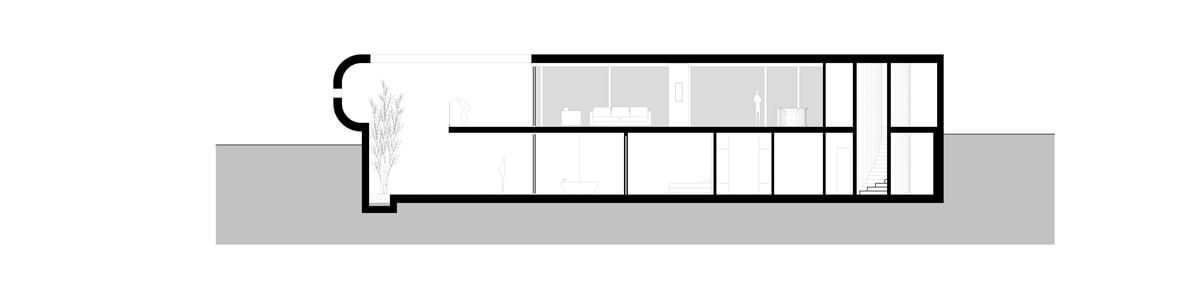

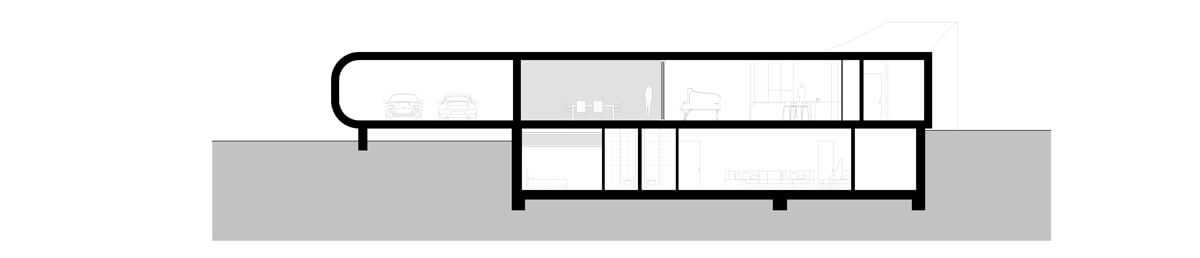

With the volume limited, Waterstudio decided to make a floor under ground level, providing extra surface within the limited dimensions of the building-envelope. Solutions for allowing daylight in the lower floor turned out to be the main architectural highlights.

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

The volume was taken up as a white frame outlining large surfaces of glass, making the whole villa rather transparent. Some touches of wood add subtlety and warmth to the scheme. The white frame curling along the facade closes off both ends of the house. In the middle the frame rises to mark the entrance.

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

The concept of transparency was maintained throughout the house by creating an open layout where, almost no doors are used. Typical eye catchers in the interior are the kitchen situated in the center of the house.

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

Beside the exterior of the Villa, Koen Olthuis designed the interior and the garden what brings the total design of the plot in harmony. In the green sloping garden the water of the New water is literally brought into the plot.

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

Architect Koen Olthuis / Waterstudio.nl

via waterstudio.nl

By Rachel B. Dyle

Curbed

March.2015

Photos Credits Waterstudio.NL

A couple years back, Disney used the space-age material Corian to build a real-life version of the futuristic house from the 1980s movie Tron. Now a firm in the Netherlands has clad a submarine-shaped home next to a lake with the material, for a very high-tech effect. Indeed, the one-story home with floor-to-ceiling windows by Waterstudio.NL has the rounded edges and elegant white shell of a living space created by Apple engineers.

Building in the rural location of Westland, Holland comes with rules about the permitted heights for structures. The resulting Corian-and-timber house is low to the ground, with a main entrance on the side of the volume, and a subterranean level that is obscured from the lake-side. “The concept of transparency was maintained throughout the house by creating an open layout where almost no doors are used,” architect Koen Olthuis writes. Photos, below:

By Contemporist

March.9.2015

Photo Credits by Waterstudio.NL

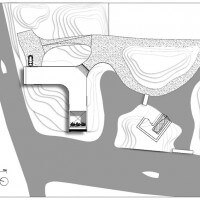

Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio.NL has designed Villa New Water, a waterfront home for a family in Westland, The Netherlands.

The description from Waterstudio.NL

From the very first moment of seeing the location for this villa, Koen Olthuis, architect and founder of Waterstudio.NL, set out to design a subtle villa that would complement its surroundings and enhance the experience of its surroundings.

In order to maintain the rural character of the location, in the project the New Water, the assignment came with strict regulations which limited the volume allowed above the ground level. These limitations eventually proved to give rise to a rather sophisticated design filled with spatial solutions.

With the volume being limited, Waterstudio decided to make a floor under the ground level, providing extra surface within the limited dimensions of the building envelope. Solutions for allowing daylight into the lower floor turned out to be major architectural highlights.

The volume was taken up as a white frame outlining large surfaces of glass making the whole villa rather transparent. Touches of wood here and there add subtlety and warmth to the overall scheme. The white frame, curling along the façade, closes off both ends of the house by framing different views of the outside. In the center, the same frame rises to mark the entrance. The entrance is designed to be a space to take in the morning sun. The façade alternates between materials like Corian and glass. A flawless material like Corian helps in realizing the strong and seamless building form as envisioned by the architect while glass helps by imparting transparency to the façade.

Besides the physical form of the villa, Koen Olthuis also designed its interior and garden. This brings together the different aspects of the design to harmonize with each other. At the site of the villa, one is welcomed by a few hills. These hills help in scripting the perfect approach for the house. As one approaches the hill, the house which is tucked away behind the hills, slowly comes into full view. The hill also serves as a natural route for the cars arriving at the house. On the other side of the water, a boathouse and a bar take shelter underneath the hill. A good view of the house can be enjoyed from the bar.

By keeping the garden green and simple, and bringing the outside water into it, the garden seamlessly blends with its surroundings. This seamless blend makes the entire area appear like one large garden from the house. To blend the green further with the house, an artificial strip of grass was used at the edge of the house. This would merge with the garden to give an appearance of the house floating over a green garden.

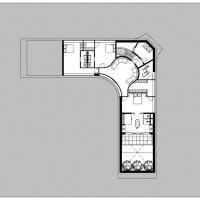

For the building, the guiding concept for design was transparency. Transparency was maintained throughout the house by creating an open layout where almost no doors were used. From the main entrance, one steps into an open hallway and is guided to the left or right by the round edges of the house. The ground floor contains a living room, kitchen and a dining room. The kitchen, located at the centre of plan in the ground floor, is surely the eye-catching design of the house. The long glass walls on the ground floor merges the outside and inside imparting a transparent feeling to the building.

The underground level contains the private functions for the family like a master bedroom, kids’ bedrooms, the wellness area and the lounge. The master bedroom with an open floor plan connects to a hidden inner garden at one end of the building. The inner garden with gravel and bamboo trees can be experienced across the wellness area from the bedroom. The lounge is situated at the centre of the underground level and becomes part of the circulation area. Though this level is completely underground and covered from outside, one does not feel so from the inside.

The furniture in the house was also designed by Koen Olthuis. Using round corners and soft materials, the furniture is in contrast to the hard Corian used elsewhere. A good example of this is the cupboard with a fireplace that divides the living area and the kitchen. Another piece of furniture is the 10-person oval shaped dining table which is closed at the ends thus not allowing people to sit at the head of the table.

In this way, the concepts of transparency and seamless flow have been translated across the different scales of landscape, architecture and interior design.

Architect: Koen Olthuis – Waterstudio.NL

Contractor: Van Leent Bouwbedrijf

Lighting: Stout Lighting

Cladding: Corian DuPont

By Philip stevens

Designboom

March.8.2015

Photo Credits by Waterstudio.NL

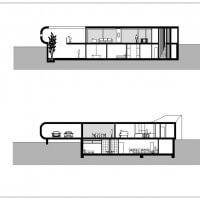

this residential property in the netherlands has been designed to comply with strict regulations that limit the height of the single storey structure. completed by koen olthuis of dutch architecture practice waterstudio.nl, the property utilizes additional floor space at a subterranean level, providing extra surface within the limited dimensions of the building envelope.

the building is formed of a white frame that outlines large surfaces of glass

the building is formed of a white frame that outlines large surfaces of glass, offset with integrated touches of warm timber. the entrance has been designed to be a space for the dwelling’s occupants to take in the morning sun, while façades alternate between corian and glass.

the dwelling integrates touches of warm timber

continuing the sense of transparency that pervades the scheme, a minimal amount of doors are used inside the home. the ground floor contains a living room, kitchen and a dining room, while bedrooms and private programs are positioned below grade. koen olthuis was also responsible for the project’s interiors and landscaping, where a simple garden introduces a flow of water inside the plot.

the entrance has been designed to be a space to take in the morning sun

the property utilizes additional floor space at a subterranean storey

the house frames views of the surrounding landscape

the ground floor contains a living room, kitchen and a dining room

the home’s bathroom at lower level

section

section

section

section

elevation

elevation

elevation

elevation

project info:

name: villa new water

location: westland, the netherlands

completed: 2014

photography: architect koen olthuis / waterstudio.nl

architect: koen olthuis / waterstudio.nl

client: van der arend family

contractor: van leent bouwbedrijf

lighting: stout lighting

cladding: corian dupont

By Alisa Tang

Thomson Reuters Foundation

March.2015

In this picture provided by Site-Specific Co Ltd, the 2.8 million baht ($86,000) amphibious house, designed and built by the architecture firm Site-Specific Co Ltd for Thailand’s National Housing Authority (NHA) rises up 85cm after architects and NHA staff fill a manmade test hole underneath the house with water during a trial run in Ban Sang village of Ayutthaya province September 7, 2013. REUTERS/Site-Specific Co Ltd/Handout via Reuters

AYUTTHAYA, Thailand (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Nestled among hundreds of identical white and brown two-storey homes crammed in this neighborhood for factory workers is a house with a trick – one not immediately apparent from its green-painted drywall and grey shade panels.

Hidden under the house and its wraparound porch are steel pontoons filled with Styrofoam. These can lift the structure three meters off the ground if this area, two hours north of Bangkok, floods as it did in 2011 when two-thirds of the country was inundated, affecting a fifth of its 67 million people.

The 2.8 million baht ($86,000) amphibious house in Ban Sang village is one way architects, developers and governments around the world are brainstorming solutions as climate change brews storms, floods and rising sea levels that threaten communities in low-lying coastal cities.

“We can try to build walls to keep the water out, but that might not be a sustainable permanent solution,” said architect Chuta Sinthuphan of Site-Specific Co. Ltd, the firm that designed and built the house for Thailand’s National Housing Authority.

“It’s better not to fight nature, but to work with nature, and amphibious architecture is one answer,” said Chuta, who is organizing the first international conference on amphibious architecture in Bangkok in late August.

Asia is the region most affected by disasters, with 714,000 deaths from natural disasters between 2004 and 2013 – more than triple the previous decade – and economic losses topping $560 billion, according to the United Nations.

Some 2.1 billion people live in the region’s fast-growing cities and towns, and many of these urban areas are located in vulnerable low-lying coastal areas and river deltas, with the poorest and most marginalized communities often waterlogged year-round.

For Thailand, which endures annual floods during its monsoon season, the worsening flood risks became clear in 2011 as panicked Bangkok residents rushed to sandbag and build retaining walls to keep their homes from flooding.

Vast parts of the capital – which is normally protected from the seasonal floods – were hit, as were factories at enormous industrial estates in nearby provinces such as Ayutthaya. Damage and losses reached $50 billion, according to the World Bank.

And the situation is worsening. A 2013 World Bank-OECD study forecast average global flood losses multiplying from $6 billion per year in 2005 to $52 billion a year by 2050.

FLOATING HOUSE

In Thailand, as across the region, more and more construction projects are returning to using traditional structures to deal with floods, such as stilts and buildings on barges or rafts.

Bangkok is now taking bids for the construction of a 300-bed hospital for the elderly that will be built four meters above the ground, supported by a structure set on flood-prone land near shrimp and sea-salt farms in the city’s southernmost district on the Gulf of Thailand, said Supachai Tantikom, an advisor to the governor.

For Thailand’s National Housing Authority (NHA) – a state enterprise that focuses on low-income housing – the 2011 floods reshaped the agency’s goals, and led to experiments in coping with more extreme weather.

The amphibious house, built over a manmade hole that can be flooded, was completed and tested in September 2013. The home rose 85 cm (2.8 feet) as the large dugout space under the house was filled with water.

In August, construction is set to begin on another flood-resistant project – a 3 million baht ($93,000) floating one-storey house on a lake near Bangkok’s main international airport.

“Right now we’re testing this in order to understand the parameters. Who knows? Maybe in the future there might be even more flooding… and we would need to have permanent housing like this,” said Thepa Chansiri, director of the NHA’s department of research and development.

The 100 square meter (1,000 square foot) floating house will be anchored to the lakeshore, complete with electricity and flexible-pipe plumbing.

Like the amphibious house, the floating house is an experiment for the NHA to understand what construction materials work best and how fast such housing could be built in the event of floods and displacement.

FLOATING CITIES?

The projects in Thailand are a throwback to an era when Bangkok was known as the Venice of the East, with canals that crisscrossed the city serving as key transportation routes. At that time, most residents lived on water or land that was regularly inundated.

“One of the best projects I’ve seen to cope with climate-related disasters is Bangkok in 1850. The city was 90 percent on water – living on barges on water,” said Koen Olthuis, founder of Waterstudio, a Dutch architecture and urban planning firm.

“There was no flood risk, there was no damage. The water came, the houses moved up and down,” he said by telephone from the Netherlands.

Olthuis started Waterstudio in 2003 because he was frustrated that the Dutch were building on land in a flood-prone country surrounded by water, while people who lived in houseboats on the water in Amsterdam “never had to worry about flooding”.

His firm now trains people from around the world in techniques they can adapt for their countries. It balances high-end projects in Dubai and the Maldives with work in slums in countries such as Bangladesh, Uganda and Indonesia.

One common solution for vulnerable communities has been to relocate them to higher ground outside urban areas – but many people work in the city and do not want to move.

Olthuis says the solution is to expand cities onto the water.

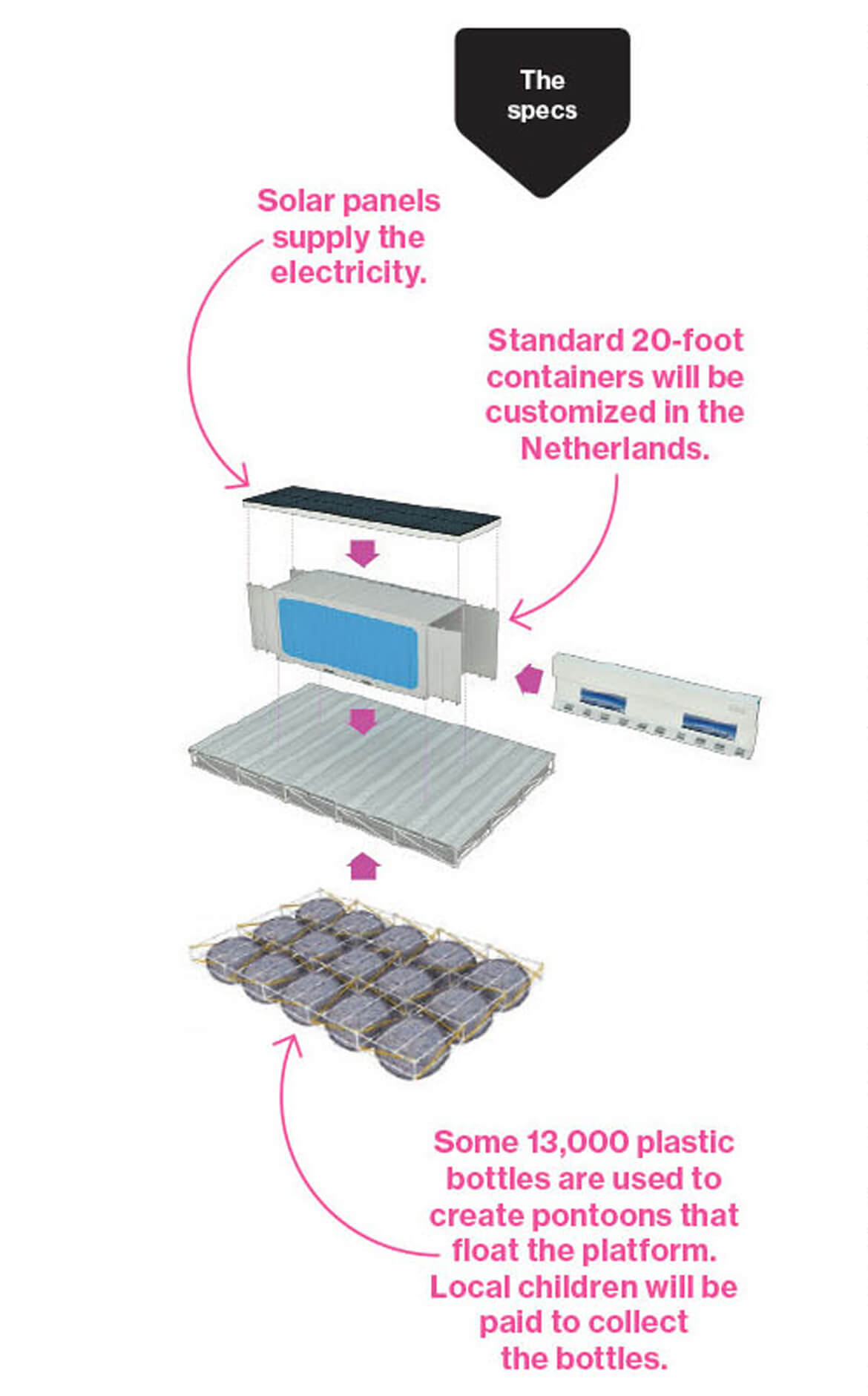

Waterstudio has designed a shipping container that floats on a simple frame containing 15,000 plastic bottles. The structure can be used as a school, bakery or Internet cafe.

Waterstudio’s aim is to test these containers in Bangladesh slums, giving communities flood-safe floating public structures that would not take up land, interfere with municipal rules or threaten landowners who don’t want permanent new slums.

“Many cities worldwide have sold their land to developers… and now when we go to them, we say, ‘You don’t have land anymore, but you have water,’” Olthuis said. “If your community is affected by water, the safest place to be is on the water.”

Reporting by Alisa Tang, editing by Laurie Goering

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

By Amy Martinez

Florida Trend

February.2015

A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling could lead to a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

(Amy Martinez)

In 2005, Hurricane Wilma destroyed a pair of dilapidated marinas in North Bay Village where Fane Lozman, a former Marine pilot and software developer, kept a two-story floating home.

The Category 3 storm struck from the south, scattering splintered docks and other large debris into more than a dozen neighboring floating homes.

For years, Lozman had relished the camaraderie and convenience of living on Biscayne Bay, especially the easy access to deep-sea diving and fishing and his favorite Miami Beach restaurants. “Your speedboat was tied up right outside your front door. And you could enjoy the south Florida water lifestyle immediately and at any time,” he says.

After Lozman’s floating home, which had been docked at the north end of the marina community, emerged relatively unscathed, he quickly began looking for another place to anchor. In 2006, he had his home towed 70 miles north to Riviera Beach and rented a slip at a city-owned marina.

His new neighbors told him not to get too comfortable, however, because a planned, $2.4-billion marina redevelopment project soon would displace them. Lozman sued Riviera Beach to stop the project. And that led to another dispute, which eventually wound up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2009, after failing to evict Lozman in state court, Riviera Beach went to federal court, seeking a lien for about $3,000 in dockage fees and nominal trespass damages.

The city argued that because Lozman’s floating home could move across water, it was a vessel under U. S. maritime law. A federal judge in Fort Lauderdale agreed, and the home was seized, sold at auction and destroyed by Riviera Beach, which cast the winning bid.

Lozman countered that his home was similar to an ordinary landbased house and should have been protected from seizure under state law. The home consisted of a 60-by- 12-foot plywood structure built on a floating platform — with no motor or steering — and could move only under tow.

Lozman’s appeal caught the Supreme Court’s eye. And in early 2013, it handed him a victory. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote in the majority opinion that because Lozman could not “easily escape liability by sailing away” and because he faced no “special sea dangers,” his home was not a vessel and not subject to seizure under maritime law. Lozman is still seeking compensation from Riviera Beach for his home’s destruction.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, Kerri Barsh, a Greenberg Traurig attorney who helped argue Lozman’s case on appeal, contacted Netherlands-based Dutch Docklands, a developer of floating homes.

Founded in 2005 by architect Koen Olthuis and hotel developer Paul van de Camp, Dutch Docklands had designed hundreds of floating homes in Holland and was looking to expand to the United States. Barsh believed the high-court ruling created an opening for the company to pursue a first-of-its-kind floating home development in south Florida.

It meant, for example, that buyers could get a mortgage and homeowners insurance, though they’d also have to pay property taxes. The Coast Guard couldn’t enter their homes to inspect for life jackets and other safety measures — and “if a gardener or maid is injured on your property, you don’t have to comply with strict workers’ comp standards,” she says. “You also may be entitled to a homestead exemption.”

Dutch Docklands now is proposing a collection of multimilliondollar floating homes at a privately owned lake in North Miami Beach. Plans call for 29 man-made, private islands that are attached to the lake bottom with telescopic piles to guarantee stability.

Each island would cost an estimated $15 million and include a 7,000-sq.-ft. home, infinity pool, sandy beach and boat dockage, plus access to a 30th “amenity” island with clubhouse. The target market is celebrities and wealthy foreigners who want both privacy and proximity to downtown Miami, says Frank Behrens, a Miami-based executive vice president at Dutch Docklands.

“Buying your own island is a very complex process, and yet it’s a dream a lot of people aspire to,” he says. “Basically, what we’re offering is a way to realize that dream. Within two minutes, you can be on land and go to a Heat game or fancy restaurant.”

Historically, floating homes have not been widely embraced in Florida. A case in point is Key West’s Houseboat Row, which started in the 1950s as a playground for the rich, but in the 1970s deteriorated into floating shacks and live-aboards. In the 1990s, then-Mayor Dennis Wardlow repeatedly criticized Houseboat Row as an eyesore and environmental hazard. And by 2002, the community’s residents had been evicted and moved to a city-owned marina at Garrison Bight.

Today, the city marina has 35 floating homes and won’t accept any more. “We prefer to take in a registered marine vessel that’s Coast Guard certified,” says marina supervisor David Hawthorne. “Most marinas have moved out of it because of the liability, and there’s just more money in” short-term boat rentals.

To succeed in Florida, Dutch Docklands will have to change perceptions. The company promotes its brand of floating homes as a response to rising sea levels and climate change. And south Florida — as ground zero for sea level rise — could prove a receptive audience. Because of how they’re anchored, the floating homes move vertically with the tides, but not horizontally, enabling them to adapt to longterm climate changes and also hold steady in storms, Behrens says.

He hopes to begin construction next year at Maule Lake, a former limestone rock quarry with direct access to the Intracoastal Waterway. But his plans may be optimistic. The company recently filed for zoning approval and still faces questions about environmental impacts, the homes’ ability to withstand hurricanes and visual effects on the surrounding community.

“One of the big struggles we’ve had in this state is coming to grips with the fact that there’s a finite amount of land and water,” says Richard Grosso, a land-use and environmental law professor at Nova Southeastern University. “We tend to not recognize the importance of open space — the aesthetic and psychological value of it.”

Condominium towers — some pricier than others — surround Maule Lake. Behrens says local residents are understandably concerned about the project.

“If all of a sudden, a foreign developer comes and says, ‘Hey, we’re going to build private islands on this lake,’ I’d be upset, too,” he says. “But if you live in a $200,000 condo, and you get a $15-million private island on the lake in front of you, where a celebrity lives, you can imagine that the value of your real estate will go up.”

Even if all goes as planned for Dutch Docklands, it’s unlikely to spark copycat projects throughout Florida. Maule Lake presents “a pretty unique set of circumstances,” says Miami environmental lawyer Howard Nelson. At 174 acres, it’s big enough to accommodate a floating development without blocking boats — “and there’s very few bodies of water where the submerged land is privately owned,” says the Bilzin Sumberg attorney.

Meanwhile, Lozman has bought 29 acres of submerged land on the western shore of Singer Island in Palm Beach County. He says he’s talking with developers about building his own floating home community.

“I could see maybe 30 floating homes out there one day,” he says. “It would essentially duplicate the North Bay Village community that was destroyed in Wilma.”