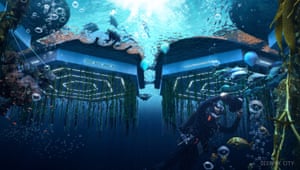

A movable home that can plunge its support deep into the water against hurricanes, or be brought on land to live off-grid.

I grew up as a Dutch girl in Canada. Among part of our family’s storytelling and legends was the tale about the Dutch boy who plugged a dyke with his thumb to save his town, the country, the world? from an encroaching sea. The flatlands people of Holland or The Netherlands as you might call them are at home with the idea of climate adverse consequences.

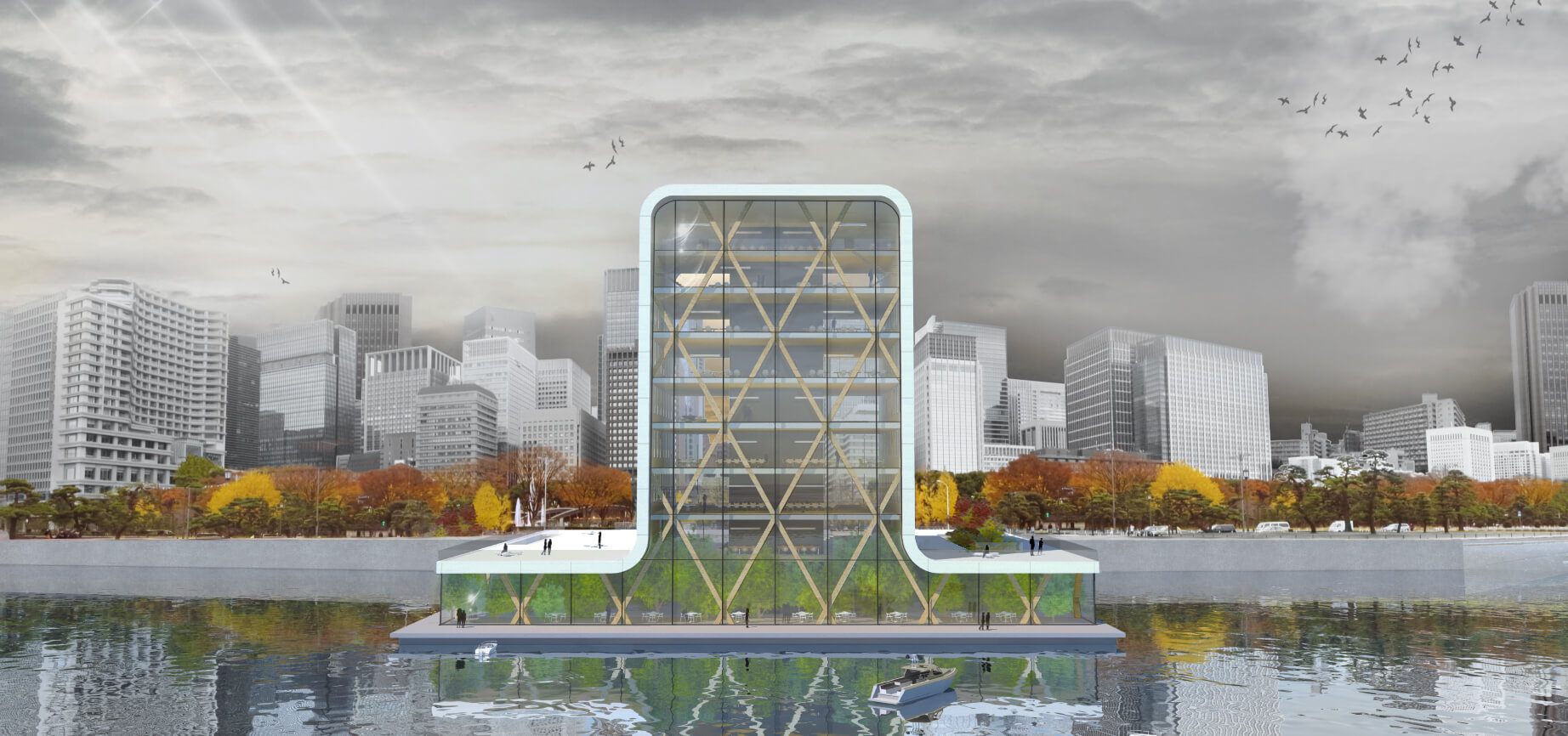

The houseboat reimagined

The national psyche is built on man against nature or man with nature, and for that the Dutch people have been reasonably doing unreasonable things against climate change and for helping the environment. See our article on the extraordinary city of Rotterdam, the home to one of resident writers, or Boyan Slat, who boldly plans to clean up the seas with his plastic-corralling invention.

Whatever floats your boat. Call it a yacht, a barge, a houseboat, but it’s not a tiny home.

While Americans might rather escape to Mars with Elon Musk, the Dutch are battening down the hatches and are offering more reasonable approaches to dealing with Mother Nature, or an angry Mother Nature. Consider the Dutch firm who has designed a solar powered yacht that can lower stilts for a more permanent mooring.

Like the modern trailer also known as the #tinyhome or #vanlife, this yacht appeals to a certain eco personality that might also want to settle like the barge dwellers in Amsterdam. It is not your father’s houseboat.

Full speed ahead

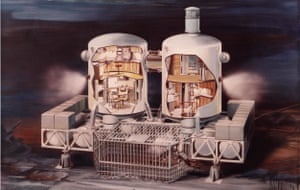

The solar powered boat is created by the Dutch architecture studio Waterstudio.NL for the yacht maker Arku in Miami, with an option of it becoming an off-grid home.

The craft is 75 feet long, is fully solar-electric, mobile and self elevating. This turn-key vessel is furnished and decorated in style by the acclaimed Brazilian furniture company, Artefacto.

Interior designed to be as fancy as this concept houseboat

The first one is for sale at a cool price of $5,500,000.

Have the captains drooling. This does not look like a houseboat. Transforms into stilted urban getaway at the port.

Arkup is a Miami, US-based company founded in 2016, to pioneer next-generation floating homes. The company rethinks life on water with its fully solar-electric, mobile and self-elevating livable yachts they call “future-proof blue dwellings.”

Weather and future proof, rain harvesting too

These livable yachts feature zero emission and silent electric propulsion which provide mobility and maneuverability. An automated hydraulic lift system, allowing the vessel to put down a stable foundation in up to 20 feet of water, ensures stability and hurricane resilience.

Sail away with me. Or anchor for the night?

The livable yacht has four bedrooms in 2,600-square-feet of indoor space, with 4,350-square-feet in total, including its terraces and balconies. To achieve its sustainability objectives, the Arkup design is 100 percent solar-powered and has systems for harvesting and purifying rainwater, for complete independence.

With Covid and potentially other climate change disasters facing us, let’s start saving? The other option might be our collective thumbs in the dyke.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)