Sea Tree at Cover

By Centre for the future of museums

Cover Trendwatch 2017

Photo Credits: Waterstudio

By Centre for the future of museums

Cover Trendwatch 2017

Photo Credits: Waterstudio

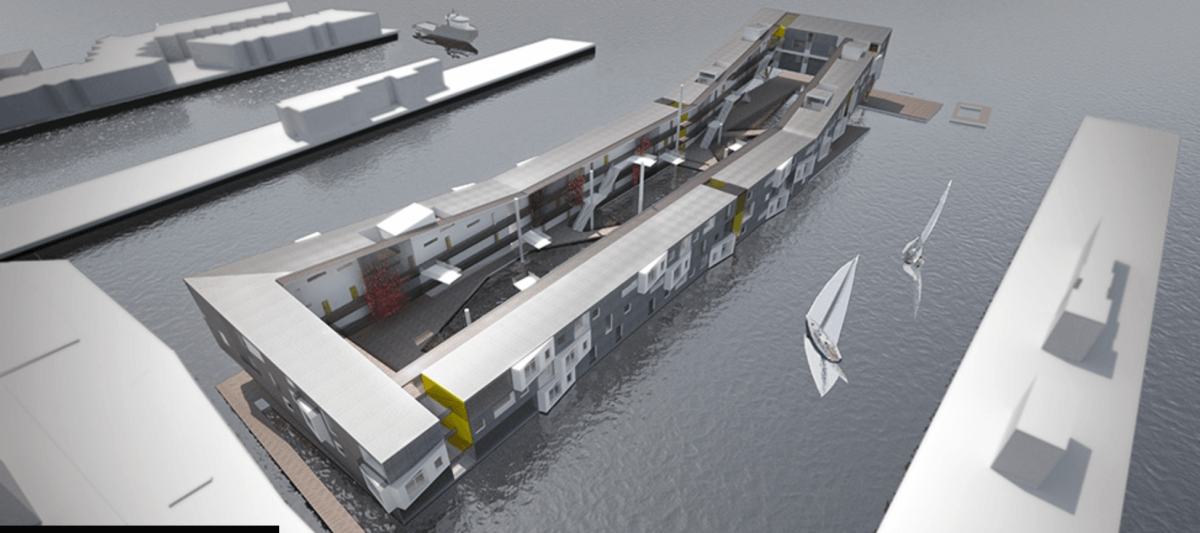

By Pierre-Mathieu Degruel

Cercle

2017

Photo Credits: Waterstudio

This prospective project created by the Waterstudio agency is designed to be located in harbours basins. This sea tree is a floating structure composed of superimposed immersed and emerged terraces. On each level a different ecosystem evolves and offers green habitats for animals rejected from citied (birds, bees, bats…). Under the sea’s surface, the tree recomposes an environment favourable to small marine creatures and, when the climate allows it, artificial coral reefs. A real modern day Noah’s Ark, this growth catalyser of fauns and flora is inaccessible to man. The cities of New York and Singapore are seriously considering installing some.

By Ed Hill

Floodlist

February.06.2017

Photo Credits: Waterstudio, UNESCO

A previous article in our series on floating architecture highlighted the work of Dutch architecture firm Architectstudio Marlies Bohmer in creating the floating community of Waterbuurt in Amsterdam. The point was made that, although it is in a developed country, it is one of the first working examples of a floating community not made up of houseboats, but actual dwellings. Another interesting Dutch architecture firm looking into floating facilities for floodprone communities is Waterstudio.nl, which, as the name implies, specializes in ‘waterborne architecture’. Waterstudio, in fact, designed several of the private floating houses of Waterbuurt, and also has designed a number of other floating houses around the world.

With about one billion people worldwide living in shantytowns, many of which are located in areas prone to flooding, the need for innovative solutions to providing decent shelter and facilities is growing daily. Since floodprone areas are least likely to receive investment for upgrading, architect Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio.nl has put forward a proposal for small scale floating facilities as a bottom up approach to improving opportunities in what he terms ‘wet slums’ – called Floating City Apps.

The Floating City App designed by Waterstudio is based on the concept of a floating shipping container fitted out for multipurpose use. The first such unit, housing 20 tablet computer workstations and 2 teaching screens, will be utilised as a classroom during the day and an Internet café in the evening. The unit has a simple construction, the modified shipping container being fixed to a base of wooden pallets floating on a wire gabion framework containing bags filled with recycled PET bottles.

The materials for the floating base are readily obtainable in developing countries so the units are easily replicable. In addition, the idea of used PET bottles for flotation is intended to provide an avenue for recycling, in order to help keep waterways clear of plastic pollution. The interior of each City App container will be fitted in the Netherlands with builtin walls and equipment, purpose designed for the specific use it is intended for. In addition, it will have solar PV panels on the roof and solar power equipment installed behind the interior walls.

Floating City Apps have been designed for six different uses; communication & education, sanitation, community kitchen, health care, garbage collection and construction. The term City App was inspired by the concept of applications, or ‘apps’ found on mobile phones. Although several phones may look the same, each is different in terms of the apps that have been loaded onto it – hence the idea that the same floating container concept can be used for different purposes.

It costs about €50,000 (US$53,000) to design, build and deliver a floating City App and, in order to realize the implementation of the concept, the Floating City App Foundation was established with Dutch aid organization Cordaid in 2013. The foundation works with several partners, including the UNESCOIHE Institute for Water Education, as well as authorities in the proposed recipient country. At a ceremony in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in June 2015, an agreement was signed between Floating City Apps, Cordaid and the Bangladeshi Computer Council of the Ministry of Post, Telecommunication and IT, in the presence of the State Minister of ICT, Mr Zunaid Ahmed Palak and the Dutch Minister of Infrastructure, Mrs Melanie Schultz, for the first Floating City App to be established in Bangladesh. Floating City App Bangladesh Netherlands Collaboration

UnescoIHE Institute for Water Education assists Cordaid with a process of identifying and mapping sites for Floating City Apps. With the aid of local agents, a ‘wet slum’ is mapped and the needs of the community assessed in order to determine the most appropriate use or uses. Shipping containers will be fitted with the relevant Floating City App designs, and the containers shipped to the nearest destination port, from which they can be transported by road. The floating platform will be constructed onsite and the container will then be attached to the platform.

Chris Zevenbergen, Professor of Flood Resilience of Urban Systems at UNESCOIHE Institute of Water Education notes that the Communication and Education App will be also used for early flood warning systems in these areas.

“We will provide recommendations to the World Bank to work differently with regard to slums upgrading” he says, “Not a one size fits all approach, but tailor made solutions for slums using local knowledge … investing in slums is not very attractive to donors. I hope this attitude changes, as slums are an important economy for the city. You can think of micro financing solutions for example”.

“Concrete solutions such as the City Apps developed by Koen Olthuis and partners should really help to attract financial support for further development” concludes Zevenbergen.

Olthuis says that there is a business model for the operation of the Floating City App. It will be leased to a local entrepreneur who will be able to provide the service to community members for a small fee. The repayment period is expected to be in the order of 20 to 30odd years. If the situation changes and the App is no longer required or viable, it can be towed to another destination, or shipped back to the Netherlands for refitting or repurposing. Olthuis explains: “So these are catalyst functions for upgrading wet slums. We have a business model. If we want to upgrade life of the poorest worldwide, one billion people, we can’t just spend money and give them money, we have to provide the tools to upgrade the lives themselves, by providing them (with) these kinds of apps.”

Since the floating City Apps are technically classed as vessels, they can qualify for insurance and private financing, which should make them attractive options for local businesses. “Cordaid’s ambition is to cocreate smart and sustainable solutions with businesses and local partners for people in need. Social enterprise holds the future” says Cordaid CFO Willem Jan van Wijk, adding “That is why we cooperated in the realization of the first Floating City App for Bangladesh.”

The first pilot Floating City App, containing the classroom, underwent its final testing for ‘seaworthiness’ and stability in the Hofvijver in front of the Dutch Parliament Building in Den Hague, on 11 March 2016. This was accompanied by the official handing over of the App to the honorable Ambassador of Bangladesh, Mr Sheikh Mohammed Belal by the representative of The Hague Municipality, Mr Karsten Klein. The pilot communication and education Floating City App is expected to be shipped to Bangladesh early in 2017, where it will be sited on the Banani Lake adjacent to the Korail slum in the capital city, Dhaka. Korail covers 150 acres (61ha) of waterside land, mostly belonging to Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Ltd, and is home to over 40,000 residents. Many of the homes are built on stilts over the water, so the placing of a Floating City App on the water will be easily accessible and not out of place. “If I were to build only floating islands for the wealthy, I would only make 150 people happy in the next 50 years,” said Mr Olthuis, who is the grandson of both an architect and a shipbuilder; “If we use this technology also to upgrade slums, we can change the lives of millions.”

By P.Kennedy

Suffolk Construction’s Content

Build smart

September.16.2016

With hurricane season at its peak, we explore how floating homes might help us adapt to bigger storms and rising seas.

The Dutch have a head start when it comes to dealing with water. The extreme weather events and rising sea level that scientists predict this century will affect millions around the globe—most of the world’s largest cities are along the coasts. But that problem has long been acute in the low-lying Netherlands, where two-thirds of the population live in flood-prone areas. Over the centuries, the Dutch have honed technologies—dikes, canals, and pumps—that keep their streets and houses dry.

Now, a new generation of Dutch engineers and architects is modeling another method. Rather than fight to keep water out, they say, why not live on it? The basic idea is not new—hundreds of free spirits live on traditional houseboats in quirky communities like Sausalito, California, and Key West, Florida. But in the Netherlands over the past few years, novel technologies have allowed developers to build roughly a thousand (and counting) stable, flat-bottomed, multi-story homes connected to land-based utilities yet designed to rise and fall with the tides and even floods. House boats, these ain’t.

And this is just the start. The Dutch are thinking bigger, and they’re exporting their floating-home vision worldwide, betting that the rest of us coastal clingers could use it. Some projects exist already, others are on the drawing board or coming soon. Let’s take a look at a few, from the workaday to the fantastical, and from overseas to right here in the States.

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and Urbanists

Photo by Roos Aldershoff, courtesy of Marlies Rohmer Architects and UrbanistsThe first of its kind, Waterbuurt (above and top) is a planned neighborhood of about 100 (eventually 165) floating houses in Amsterdam’s IJmeer Lake, part of a freshwater reservoir dammed off from the North Sea in the 1930s. Waterbuurt broke ground—er, water—in 2009, and was largely complete by 2014. Connected by jetties, the structures are three-story, 2,960-square-foot houses built of wood, aluminum, and glass.

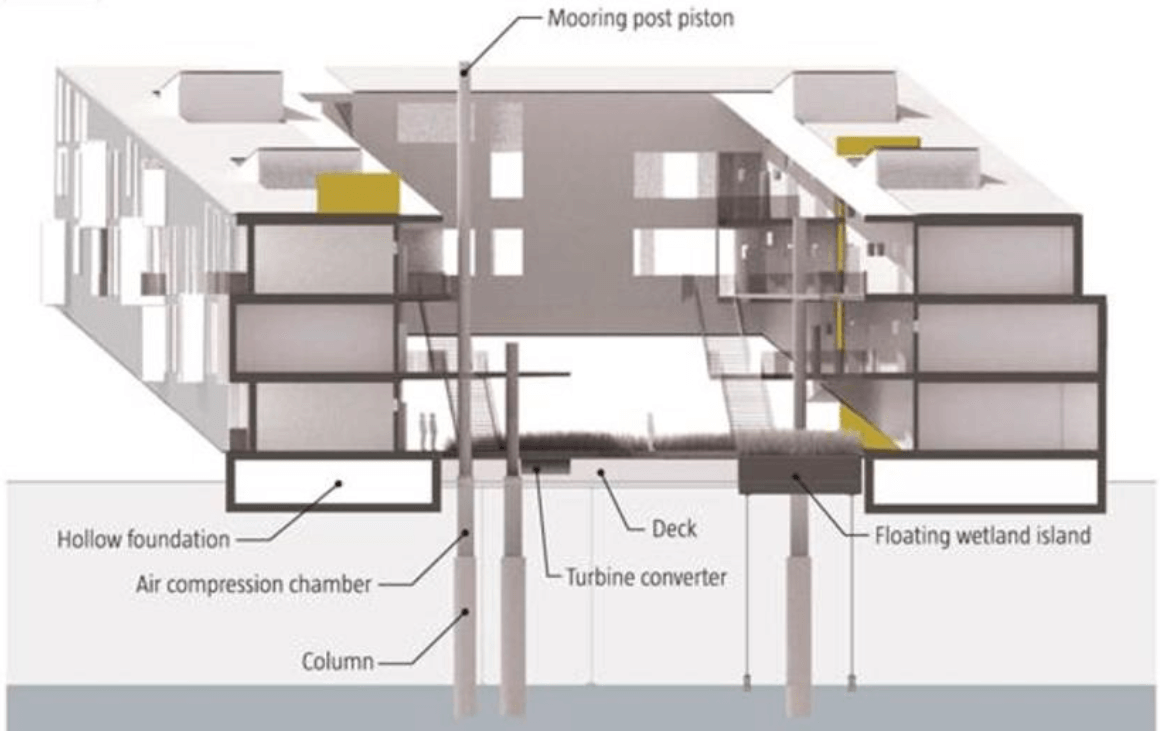

And the foundations? Floating concrete tubs. Each house is designed to weigh 110 tons and displace 110 tons of water, which—as Archimedes could tell you—causes it to float. (The bottom floor is half submerged.) To prevent rocking in the waves, the house is fastened to two mooring posts—on diagonally opposite corners of the house—driven 20 feet into the lake bed. The posts are telescoping, allowing the house to rise and fall with the water level. Flexible pipes deliver electricity and plumbing.

Because any crack in the foundation tub could cause the house to sink, there can’t be any joints; builders pour the entire basement in one shot—much like the parking garage of the Jade Signaturecondo complex in Florida. In a facility 30 miles away from the IJmeer Lake site, crews use special buckets that pour 200 gallons per minute to finish all four walls and the floor in a single shift.

Just four months elapse before the entire house is built; then it’s towed by tugboat—30 miles through canals and locks—to the plot. The transportation is a major reason the houses cost about 10 percent more than an average home in Amsterdam, though they’re still aimed at the city’s middle class. The houses were designed by architect Marlies Rohmer, for developer Ontwikkelingscombinatie Waterbuurt West.

Photo by Marcel van der Berg

Photo by Marcel van der BergOnce secured to its mooring posts, the structure is formally considered an immovable home, not a house boat. (Although owners have the option of naming their waterborne homes as sea captains do. One couple calls theirs La Scalota Grigia—Italian for “The Grey Box.”)

With high ceilings and straight angles, a house in Waterbuurt “feels like a normal house,” wrote a New York Times reporter who toured one. But some residents say they do feel their home swaying when the wind kicks up.

One other drawback, or at least challenge: Residents have to decide before the house is even built where they’re going to place furniture, because that will affect its balance. The walls are built to varying thickness, depending on the layout submitted. What if you inherit a beloved aunt’s piano after you move in? Or have another child and need to buy a bunkbed? To compensate, homeowners can install balance tanks on the exterior or Styrofoam in the cellar, or carefully move furniture around or even deploy sand bags. A bit of a hassle, but perhaps with an eye on rising sea levels, that’s a risk Amsterdammers are willing to take.

At the luxury end of the market, there’s Citadel, which aims to be the world’s first floating apartment complex. Construction began in 2014. Citadel uses the same technology as Waterbuurt—floating concrete base, mooring pistons—but on a larger scale, in the sense that this will be one massive deck supporting a multifaceted apartment building, rather than a place for many individual houses to dock. Think of it as Waterbuurt with butlers. (And underwater parking and other amenities).

Citadel was designed by pioneering architect Koen Olthuis’ Waterstudio in partnership with master developer Dutch Docklands. The concrete caisson foundation will measure 240 by 420 by 9 feet, supporting 60 sleek, aluminum-clad apartments in an irregular arrangement that from the air will look a bit like a scattering of stacks of jigsaw puzzle pieces. Palm trees will sprout from courtyards. Green roofs are planned, and the developer hopes to have Citadel use 25 percent less energy than a similarly-sized complex on land.

One thing remarkable about Citadel is the body of water it will float in: a lake that doesn’t exist yet, though it did once. Construction is taking place in a polder, one of the Netherlands’ many low-lying areas that is only dry because pumps work 24-7 to keep the water out. Once construction is complete, the pumps will shut off, and the area will be re-flooded, to 12 feet deep. Eventually, Dutch Docklands plans to build five more complexes in the same un-manmade lake, dubbed New Water.

This is all well and good for the Dutch, but what about the flat, flood-prone coastal regions here in the USA? Like, for example, Florida? Well, the Dutch have thought of that. Another Waterstudio-Docklands project is Amillarah Floating Private Islands Miami, located in Maule Lake. A former limestone rock quarry, the privately owned lake is an inlet a mile and a half from the ocean, a bit north of Miami Beach.

Dubbed a “villa flotilla” by the Miami Herald, the complex will consist of 29 6,000-square-foot condos priced at $12.5 million each. As with Citadel and other Dutch Docklands projects, there are plans to boost the Maule Lake project’s sustainability, in this case with solar and hydrogen-powered generators.

Though similar to Citadel in the Netherlands, this project wouldn’t have been possible Stateside without a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision that floating homes could be considered real estate, not boats. As the Herald explained, would-be buyers of Amillarah condos can get a mortgage and homeowners’ insurance, and the Coast Guard can’t bust in and inspect for life jackets.

Maule Lake will be out of reach for most Floridians financially, but if the ambitious project succeeds, it will provide visual evidence to Miami that floating houses can be done, and perhaps inspire larger, more modest developments like Amsterdam’s Waterbuurt.

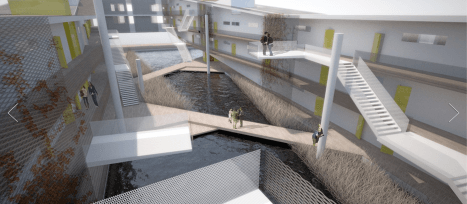

In Boston, architect Brian Healy, for the local office of Perkins+Will, won awards in 2013 for his design of Floatyard, a proposed apartment complex that would stretch out onto the Mystic River from the Charlestown Navy Yard, using much of the same technology as the abovementioned Dutch initiatives. Were Floatyard and similar projects to become reality here, Healy argues that they would not only help the city adapt to rising seas but also revitalize disused shipyards (for example, in East Boston and Quincy) and reorient Boston—historically a seaport—toward its natural center, the harbor.

What makes Floatyard unique is its central courtyard: a floating wetland island, built above the foundation, to be seeded with native marsh grass and aquatic wildlife. The design also includes a plan to harvest tidal energy via the structure’s mooring post pistons.

Elder statesman of architecture criticism Robert Campbell could have been talking about any of the above floating buildings when he wrote of Floatyard: “Like a lot of good ideas, this one is just crazy enough to make sense.” Given the prediction for the ocean to rise between three and five feet by the year 2100, it might be more crazy not to build on floating tubs.

By Rachel Keeton

Next City

October.01.2014

Resilient Cities

The Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat. (Photo by Waterstudio)

In a quiet, shady street in Rijswijk, the Netherlands, Koen Olthuis and the design team at Waterstudio are changing the world. From this deceptively nondescript headquarters, Waterstudio is designing the cities of the future. If Olthuis has his way, they will be safer, more flexible and more resilient than current cities. How will he do this? Olthuis is designing floating cities. As we sit down at the table, the busy office buzzing around us, my first question to Olthuis is direct: “How realistic are floating cities?” Olthuis grins and nods, he’s heard this question before.

Floating cities have captivated society’s imagination for centuries, from the development of Venice a millennium ago to Triton, designed for Tokyo Bay by Buckminster Fuller in the 1960s. But it wasn’t until the last decade or so that more fully realized, just-might-actually-happen sea-based urban endeavors have emerged, made more urgent by rising sea levels and rural-to-urban migration. In the last six months, Business Insider, Bloomberg and The Guardian have all run stories asking the same question: “Has the time come for floating cities?”

Olthuis dives right in: “It depends what you mean by ‘floating city.’ If you’re talking about a community of 100,000 in the middle of the sea, we’re probably about 50 years away from achieving that. If you want it to be completely self-supporting, it’s probably going to take another 20 years after that.” Bending over a roll of tracing paper, Olthuis quickly sketches a timeline of floating architecture. If we take it from the present moment, about midway on Olthuis’ sketch, hybrid cities are the next step in this evolution. Built on the edge of the existing city, these developments could easily connect to electrical and sanitation grids. “Technically, this stuff is easy to engineer: we’re already there,” says Olthuis. That makes them more straightforward to regulate and less risky for investors.

It’s the images of sparkling new cities lost at sea that have people raising skeptical eyebrows. “We’re working on a set of guidelines, a toolbox that will ultimately get us to the floating city you imagine. We’re working out these concepts that all give a glimpse of the future, but we have to find out what we need, how it works and what it adds to current urban development. We have to map out the steps to get us from today to the future and have to think about the entire process. And we need that, because if we don’t answer these questions, we get all these architects with beautiful renderings and fantastic ideas, but they don’t tell you the steps in-between and they don’t tell you why. And then your question is, but how realistic is it?”

Listening to Olthuis, it quickly becomes apparent that this scenario is actually incredibly realistic. With the technology and market demand in place, it’s political will and ownership issues that are holding development back. People have trouble imagining an urban future where city halls can be swapped for theaters on opening night, or entire Olympic villages can simply be towed around the world instead of rebuilt every four years. “Our cities today are too static. We make static cities for dynamic societies. We should be cities that can adapt to new demands and external influences. Water gives us three things: it adds more space (in old harbors, rivers, lakes), it’s safer (from storm conditions, rising sea levels) and it’s flexible. If you only construct the buildings you will use for 100 years statically, on land, and construct the buildings you will only use for 20 to 30 years flexibly, on water, then you’ve created a much more adaptable city that can respond to changing needs quickly and efficiently. If someone isn’t happy with their house anymore, they can ship it to someone who needs it in the Philippines.”

Governments are slowing starting to see the potential of this approach. If cities like New York or Tokyo build two to three percent of their development on the water, they can sell this to developers, tax the owners and create a more flexible city. Win-win. Governments are interested in this because it presents a new market for them. While most land is privately owned or already built up, by changing policies to make floating structures available the government expands its real estate. It’s a business model that is attractive because it solves multiple problems. Floating structures can reinvigorate former industrial areas like old harbors or riversides, they can adapt to extreme weather conditions better than traditional structures and they create a profit from space that is currently unmarketable.

Still, the idea of bobbing around permanently makes some people understandably squeamish. If one floating house goes up and down on waves, it may tilt: one half sits on the crest of a wave and the other end is stuck in the trough. This doesn’t happen when you start to build big enough to have a project that is always supported by multiple waves. On the water, the bigger the project, the more stable is it. In fact, floating cities are actually something that works better all around on a larger scale. If Olthuis is designing a watervilla for a single family, he has to calculate all kinds of factors to design a single, site-specific home. This ends up costing a lot more than a traditional house. If he’s designing a community of 10,000 water villas, the price is the same as a comparable urban development.

Moving functional amenities like prisons, stadiums and airports onto the water is already becoming more common as cities try to create more elbowroom for residents. Alvaro Siza’s recently completed chemical plant in Huai’An City, China, was built on the water, and BREAD Studio recently designed a floating cemetery to be rafted off the coast of Hong Kong – a city long on elderly citizens but short on space. Today there’s a floating skate park on Lake Tahoe and floating freshwater pools in the River Thames. There’s even a floating cinema in London by UP Projects, echoing Aldo Rossi’s iconic Il Teatro del Mundo from 1979.

Less whimsical but more crucial are floating developments for informal settlements located on waterfronts or in delta regions that are most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Kunlé Adeyemi’s floating school in Makoko, a picturesque shantytown in Lagos, Nigeria, will provide classroom space for 100 students. The problem with one-off projects like NLE’s floating school, according to Olthuis, is that the Lagos government has been against it from the beginning (it’s been declared illegal), and it’s not even being used because of this controversy. “If you want to really make a difference, it can’t be just one thing. It has to be a system with a sound business model,” says Olthuis.

“I think the current generation of architects really wants to help, they want to make a difference. If you tell the story of one billion people living in slums in places like Thailand, India, Bangladesh — where water is threatening those people and no one is helping them because anything that gets built can be wiped out by the next tsunami — we think, well we have to help those people. The City Apps project — retrofitted shipping containers floating on trash — is a system where we bring in floating schools, sanitation, electricity, water treatment facilities, bakeries, internet cafes, or whatever is most needed. We can connect these floating functions to the slums or disaster sites and they will slowly help upgrade these areas.

We’re investing in this ourselves, by funding the first prototype that will be deployed to Manila. We’ve started a foundation, working with Cordaid, where we lease the City Apps directly. It costs us about €50,000 to design and build a City App in a recycled shipping container, then it gets deployed to wherever it’s needed and there they construct a floating platform out of old plastic bottles and other rubbish. Ultimately, it should be a business model that provides an entrepreneurial opportunity for residents of these areas. It’s cheap — they just pay a small monthly fee — it’s safe, since it goes up and down with the water, and it provides a solution to real problems. If you don’t need it anymore, you just send it back to us and we lease it out to someone else. Next year we’ll have ten, the year after, a hundred, and it will grow to a few thousand containers around the world. Of course, it’s just a small help to these millions of people, but we hope it will act as a model and show that we can shift from giving aid to providing an opportunity for employment.”

On the other end of the inclusiveness spectrum, there are politically motivated projects like the Seasteading Institute’s Floating City. Promoted with viral videos and backed by private donors and crowd funding, these mobile communities are envisioned as new experiments in governance, giving each community total political autonomy over itself. After attending the third Seasteading Institute conference in 2012, Josh Harkinson of Mother Jones summarized the Institute as “a hacker’s approach to government with a Waterworld-esque conception of Manifest Destiny. More than a mere repository for political dreamers, it brings together engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs of the sort one often finds in the Bay Area: techtopians who might be brilliant or delusional — or both.”

Olthuis accepts that different floating communities may have different goals. “I think we’ve only seen about 10 percent of the ideas that are actually possible in terms of floating architecture. In the next century, we’ll have thousands and thousands of new architects who can think about these possibilities.” Waterstudio calls their floating designs “scarless,” meaning they can be repositioned without leaving any trace of their presence. But the next step is to build designs like the Sea Tree, a floating natural habitat that would give small fish a sanctuary, increase the oxygenation of water, and potentially collect trash as it drifted about.

Olthuis is adamant that we have to embrace the water rather than run from it — we don’t have any other options. “Today, the momentum is there because we see the effects of climate change and we can’t be sure about our safety. We see millions of people moving to the cities and we don’t know where they will live. These issues are finally making people think twice about floating architecture. If we can convince them that it’s also financially profitable and help governments change building regulations, we’ll have a future where it’s normal to see cities that are 95 percent built on land and five percent built on water — just enough to give them the flexibility they need for an uncertain future.” It’s a revolutionary way of thinking about the city: puzzle pieces that can be reconfigured according to changing needs and desires. Olthuis’ concern with marketability and political interest makes his story much more convincing than the glossy renderings popping up on design websites. “Many architects are using technical solutions to approach this problem and just showing us the images without any information. I think a floating city is only something that works when it makes sense economically, socially, spatially — and should also look nice. It should be a normal development that is open to everyone, rather than an alien form for an elite few.” His belief in the advantages of these projects is clear, and the built examples in the Maldives, China and the Netherlands are proof of their viability. Just as it was for Buckminster Fuller 50 years ago, the floating city remains an exciting and mysterious model of urban development. Only now, it’s closer than ever. And Koen Olthuis can tell you exactly how to build it.

By Beatriz Portinari

CLUB + RENFE

Los arquitectos del futuro proponen una Atlántida biososteniblecomo respuesta al cambio climático y la utopía de una colonización oceánica.

“El mar no pErtEnEcE a los déspotas. En su superficie, aún pueden ejercer sus inicuos derechos, pelearse, devorarse y transportar todos los horrores terrestres, pero a treinta pies de profundidad, su poder

cesa. ¡Ah, señor, viva usted en el seno de los mares! ¡Solo ahí existe la independencia! ¡Ahí no reconozco señor alguno! ¡Allí soy libre!”. Con estas palabras, Julio Verne convirtió al capitán Nemo y su Nautilus en los pioneros de la llamada “colonización oceánica”, en 1870. Casi 200 años después de 20.000 leguas de viaje submarino, ingenieros y arquitectos ofrecen propuestas viables que van desde hoteles flotantes o flotels a cruceros-residencia para millonarios como The World y finalmente la utopía social y política de las naciones semi-sumergibles que propone el Seasteading Institute.

Pero, ¿por qué querría el hombre vivir en futuristas ciudades acuáticas?

Quizá por placer, por evadir impuestos en aguas internacionales o por pura necesidad medioambiental. Según los expertos en cambio climático y el Informe España: hacia un clima extremo, publicado por Greenpeace en 2014, se espera que a finales del siglo XXI la subida del nivel del mar por el deshielo del Ártico provoque una catástrofe climática y humanitaria que afectará al uno por ciento del territorio de Egipto, el 7% de Países Bajos, el 17% de Bangladesh y hasta el 80% de las Maldivas. En España, las mediciones indican que “durante la segunda mitad del siglo XXI, hasta 202 hectáreas de terreno se encontrarán en riesgo de inundación en la costa vasca. De esta extensión, la mitad corresponde a terrenos urbanizados, tanto zonas industriales como residenciales”. El peligro es real. Las estimaciones más pesimistas dicen que en 2030 habrá 50 millones de refugiados climáticos en el planeta, que ascenderían a 200 millones en el año 2050. ¿Qué hacer con esta población sin tierra? Más allá de previsiones, la evidencia está en el archipiélago de Kiribati, al noreste de Australia, donde 100.000 habitantes buscan territorio para trasladar todo un país porque el suyo ha comenzado a desaparecer bajo el mar. El gobierno de Kiribati ha comprado terreno en las islas Fiji para instalar a su población e incluso se ha planteado los diseños anfibios de uno de los arquitectos más preocupados por el medio ambiente, Vincent Callebaut, autor de los prototipos acuáticos Lilypad, Physalia y el más reciente Aequorea.

‘aRQuibiÓTica’ conTRa El cambio climáTico

“La anticipación urbana es fundamental para crear la ciudad del mañana, que considero imprescindible en la transición energética. Lo que llamo ‘arquibiótica’ es la solución

biotecnológica de la arquitectura a la crisis ambiental que sufrimos. Me inspiro en el biomorfismo, el biomimetismo y

la biónica, donde la ingeniería puede repetir esquemas de la naturaleza y aprovechar las nuevas tecnologías de comunicación”, explica Callebaut, a quien el Ayuntamiento de París

acaba de encargar el rediseño de la ciudad. De momento, sus audaces prototipos todavía no han encontrado océano donde iniciar la revolución verde.

Quien sí ha comenzado la construcción real de un atolón artificial para salvar a su población del mar es el Gobierno de las islas Maldivas, que ha firmado una alianza comercial con la empresa holandesa Dutch Docklands, experta en ganar terreno al agua. Si el entorno paradisíaco de las Maldivas va a desaparecer bajo el mar, nada mejor que empezar a construir una réplica flotante para mantener el turismo. Para ello se ha encargado el proyecto The 5 Lagoons al estudio de arquitectura Waterstudio, que dirige Koen Olthius, considerado “uno de los 100 eco-arquitectos que cambiarán el mundo” y que apuesta por el paso de las ciudades verdes a las ciudades azules sobre el agua. “No debemos tener miedo al posible aumento del nivel del mar, sino verlo como una oportunidad para mejorar nuestras ciudades. Si la costa española se puede ver afectada, debería empezar hoy mismo a considerar soluciones. Estas plataformas flotantes deberían ser eco-sostenibles, más duraderas y flexibles”, cuenta Olthius. El arquitecto va más allá e imagina “bellos parques en el agua, dinámicos, capaces de cambiar de forma y función en cada estación; el turismo ha sido siempre muy importante en la economía española y creo que estas extensiones flotantes podrían atraer más turistas.

Podría aportar al mismo tiempo seguridad y prosperidad a la costa. La tecnología está disponible, sólo sería necesario que fuera económicamente viable”.

El Seasteading Institute, creado en 2008 con importantes inversores como Peter Thiel, fundador de PayPal, va más allá y propone ciudades-estado independientes en aguas internacionales. Sin embargo, su utópico proyecto Floating City aún no ha visto la luz. “Técnicamente las ciudades anfibias son viables, pero deberían responder a una necesidad económica, legal y política real porque de lo contrario el proyecto no es rentable. Si tienes una plataforma que no pertenece a ningún país, no puedes defenderte de ataques piratas, por ejemplo. Para el problema del cambio climático existen soluciones más baratas como se ha visto con el relleno de tierra que está haciendo Singapur en su costa”, advierte el Ingeniero Naval y Oceánico, Miguel Lamas, experto en plataformas flotantes y antiguo colaborador del Seasteading Institute. En su tesis Establecimiento de comunidades autónomas en alta mar: opciones presentes y evolución futura hace un análisis realista de los posibles escenarios. Aunque estas comunidades en alta mar serían beneficiosas porque fomentarían el uso de las energías renovables de origen marino y la protección del hábitat oceánico, hoy por hoy no existe economía ni sociedad que respalde a corto plazo un costoso proyecto como las Ciudades Flotantes autónomas. Parece que la utopía de la colonización oceánica tendrá que esperar.

By Tafline Laylin

Inhabitat

December.2015

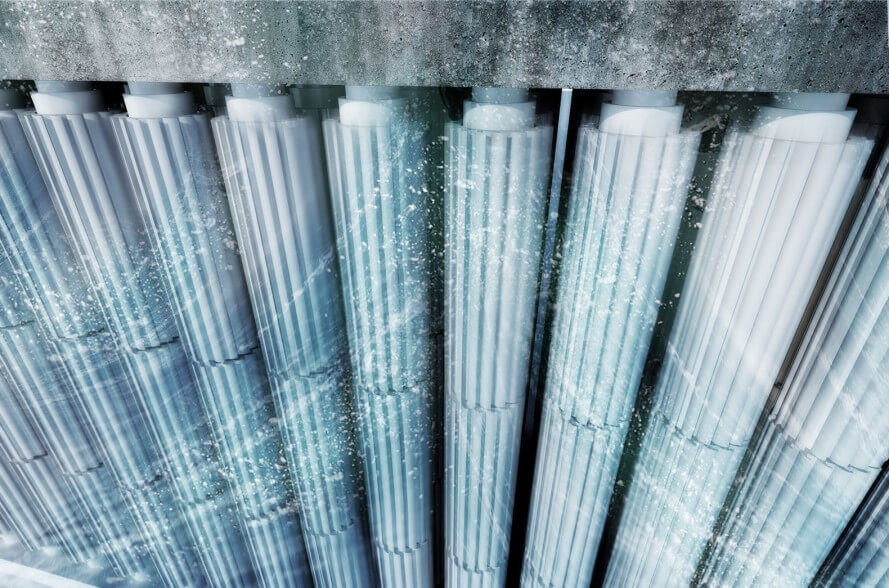

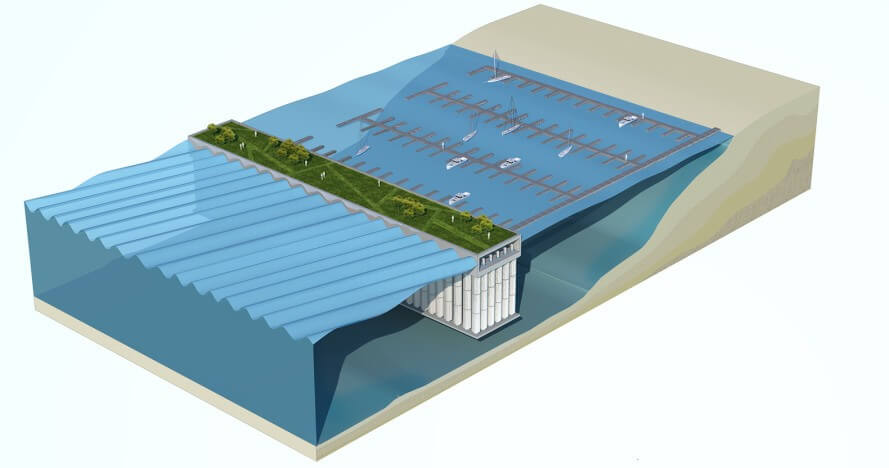

Certain world leaders might be dragging their feet on addressing climate change, but in the meantime, Koen Olthuis and the rest of the Waterstudio crew are working on solutions that we can use today. The Blue energy floating sea wall is a floating breakwater that doubles as an energy generator. Called The Parthenon, the floating breakwater not only stems the crash of water pushing into a harbor, but harvests the tremendous energy a wall of water like that can generate.

Waterstudio used the Hudson River to illustrate their new design’s function. “In a harbour on the Hudson river in New York the wave conditions are so strong that a sea wall must protect its boats. The strong current in the river is constantly attacking it and water is pushing itself against and through the fixed wall, which results in more corrosion of the sea wall every year.”

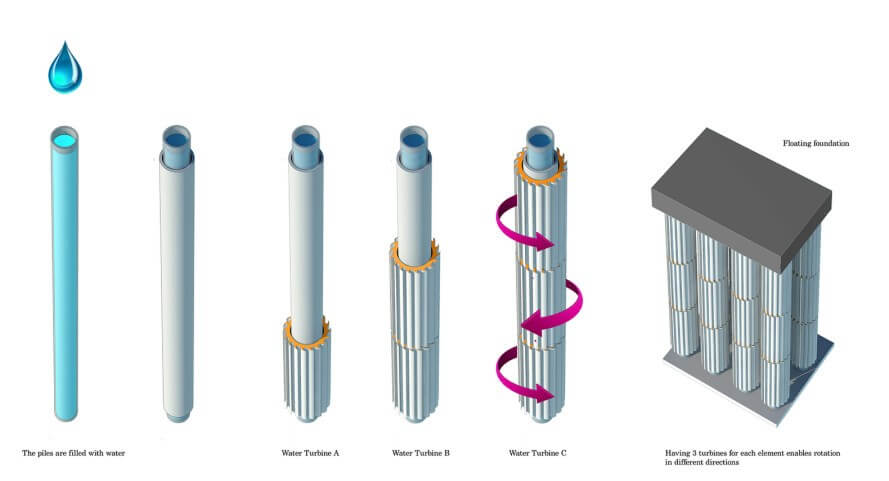

The floating sea wall acts as a permeable breakwater that converts the wave power into electrical energy while reducing the waves’ impact on the harbor at the same time. “The floating breakwater lives with the force of the river instead of fighting it,” they told Inhabitat in an email.

Related: Aquatect Koen Olthuis tells Inhabitat how to embrace rising sea levels

The columns of the sea wall are comprised of 3-foot cylinders that rotate – both clockwise and counter clockwise – at low speed. The energy created by this rotation is then captured in a concrete box inside the floating platform. The cylinders are filled with water to give the structure flexibility without affecting in any way the efficacy of the wall in reducing the wave’s impact on the harbor. The whole thing is then anchored to the riverbed, and the top can double as an urban green space or boulevard.

“The Parthenon blue energy sea wall resembles the column structure of the famous ancient temple in Greece,” according to Waterstudio, “but divers see it as a part of the sunken city of Atlantis.”