By Kyle Chayka

The New yorker

2024.March.25

In a corner of the Rijksmuseum hangs a seventeenth-century cityscape by the Dutch Golden Age

painter Gerrit Berckheyde, “View of the Golden Bend in the Herengracht,” which depicts the

construction of Baroque mansions along one of Amsterdam’s main canals. Handsome double-wide

brick buildings line the Herengracht’s banks, their corniced façades reflected on the water’s surface.

Interspersed among the new homes are spaces, like gaps in a young child’s smile, where vacant lots

have yet to be developed.

For the Dutch architect Koen Olthuis, the painting serves as a reminder that much of his country has

been built on top of the water. The Netherlands (whose name means “low countries”) lies in a delta

where three major rivers—the Rhine, the Meuse, and the Scheldt—meet the open expanse of the

North Sea. More than a quarter of the country sits below sea level. Over hundreds of years, the Dutch

have struggled to manage their sodden patchwork of land. Beginning in the fifteenth century, the

country’s windmills were used to pump water out of the ground using the hydraulic mechanism

known as Archimedes’ screw. Parcels of land were buffered with raised walls and continuously

drained, creating areas, which the Dutch call “polders,” that were dry enough to accommodate

farming or development. The grand town houses along Amsterdam’s canals, as emblematic of the city

as Haussmann’s architecture is of Paris, were constructed on thousands of wooden stilts driven into

unstable mud. As Olthuis told me recently, “The Netherlands is a complete fake, artificial machine.”

The threat of water overtaking the land is so endemic to the Dutch national psyche that it has inspired

a mythological predator, the Waterwolf. In a 1641 poem that coined the name, the Dutch poet and

playwright Joost van den Vondel exhorted the “mill wings” of the wind pumps to “shut down this

animal.”

Olthuis has spent more than two decades seeking ways to coexist with the wolf. His architectural firm,

Waterstudio, specializes in homes that float, but its constructions have little in common with the

wooden houseboats that have long lined Dutch canals. Traditional houseboats were often converted

freight ships; narrow, low-slung, and lacking proper plumbing, they earned a reputation in the postwar

period as bohemian, sometimes seedy dwellings. (Utrecht’s onetime red-light district was a row of

forty-three houseboat brothels.) Waterstudio’s signature projects, which Olthuis prefers to call “water

houses,” look more like modern condominiums, with glassy façades, full-height ceilings, and multiple

stories. In the past decade, as severe weather brought on by climate change has caused catastrophic

flooding everywhere from Tamil Nadu to New England, demand for Waterstudio’s architecture has

grown. The firm is currently working on floating pod hotels in Panama and Thailand; six-story

floating apartment buildings in Scandinavia; a floating forest in the Persian Gulf, as part of a strategy

to combat heat and humidity; and, in its most ambitious undertaking to date, a floating “city” in the

Maldives.

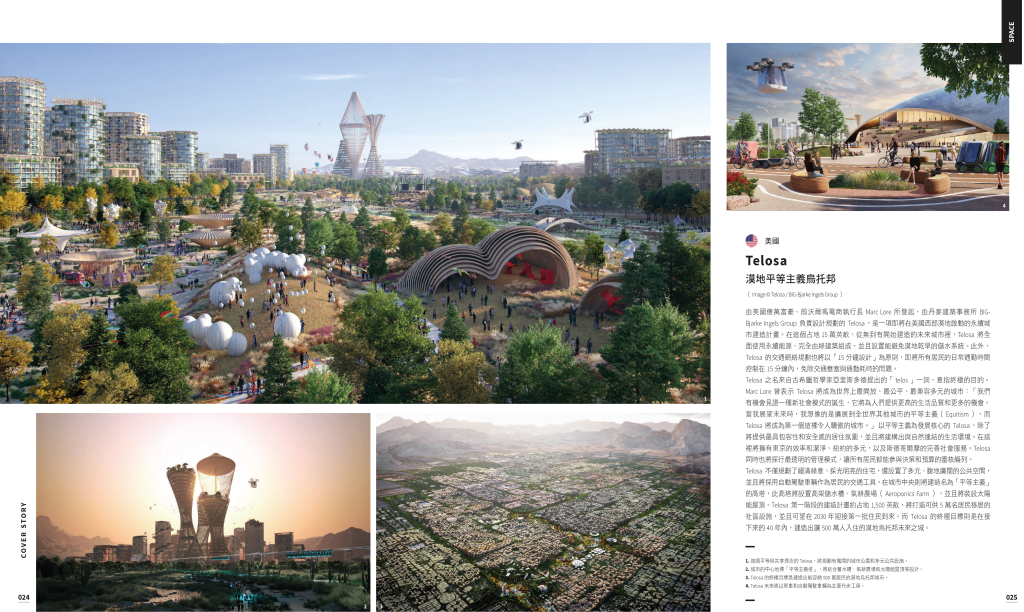

Waterstudio projects such as a two-story, two-thousand-square-foot floating villa in the Dutch city of Leiden amount to what Olthuis calls “innovation at

the cost of the rich.”Photograph by Giulio Di Sturco for The New Yorker

One evening in January, I met Olthuis for dinner at Sea Palace, a Chinese restaurant in a three-story

pagoda built on a boat hull in the harbor near the center of Amsterdam. Created based on a similar

structure in Hong Kong, it has seating for some nine hundred people and bills itself as the largest

floating restaurant in Europe. On its opening night, in 1984, the boat began to sink, and more than a

hundred diners had to evacuate; the builders’ calculations hadn’t accounted for the fact that Hong

Kongers weigh less on average than the Dutch. In the end, the surplus crowd was served dinner al

fresco on the shore, and, the story goes, a Dutch tradition of Chinese takeout was born.

Olthuis is fifty-two years old and gangly, with a stubbled chin and graying hair swept back in the

shaggy style typical of Dutch men. He dresses in all black year-round, even, to his wife’s chagrin,

packing black trousers for summer vacation. But his vibe is less severe aesthete than restless inventor.

He drives a plug-in hybrid car that he never bothers to charge, eats instant ramen every morning for

breakfast, and had an entire floor of the home he designed for his family, in Delft, carpeted in

AstroTurf, so that his three sons can play soccer indoors. During our dinner, he drank two Coke

Zeros, which augmented his already considerable aura of activity and churning thought. Midway

through the meal, he picked up his chopsticks and held one upright in each fist, to illustrate the poles

that tether many of Waterstudio’s buildings to the beds of the bodies of water they float on.

He put down one chopstick and picked up a bowl of kung-pao chicken, which represented the

concrete foundations that, somewhat counterintuitively, allow many of his houses to float. “Concrete

weighs 2.4 times more than water, so if you make a block of concrete it will immediately sink,” he

explained in lightly accented English. “But if you spread it out, if you make a box filled with air, then

it starts to float.” The poles are anchored sixteen feet into the water bed and extend several feet above

the surface; the floating concrete foundation is fastened to the poles with rings. Olthuis slid the bowl

slowly up and down the length of the chopstick to demonstrate how the foundation can rise and fall

along the poles with the fluctuations of the water. Whereas Sea Palace is essentially a glorified barge,

resting atop the water on pontoons, Waterstudio’s concrete bases give its projects a stability

approximating that of land-bound construction, at least when the waters beneath are still. “You can’t

compare them,” Olthuis said of his buildings versus the one we were sitting in.

He peered through the restaurant’s windows at the bustling commercial strip onshore. “This area

would be fantastic to place maybe a series of floating apartment buildings and affordable housing for

students,” he said.

The Dutch government’s approach to water management is primarily defensive. New pumping

stations are being built to keep pace with the higher volumes of water brought on by climate change.

A program to raise seawalls has been funded through 2050. But Harold van Waveren, the top expert

on flood-risk management at Rijkswaterstaat, the agency that oversees the country’s larger canals,

dams, and seawalls, told me that the threats posed by water have become increasingly unpredictable

as the sea level rises and storm surges grow more extreme. “We just finished a study that says at least

three metres, even five metres, shouldn’t be a problem in our country,” he said, referring to projected

surges. “On the other hand, will it stop at three metres? You never know.”

Olthuis believes that the Netherlands should give certain flood-prone parts of the land back to the

water—a managed surrender to the elements rather than a Sisyphean battle against them. He held up

the dish of chicken, now representing one of the country’s polders. The polders, numbering more than

three thousand, are like a series of bowls, he said. For centuries, the Dutch have made their land

habitable by laboriously keeping the bowls dry. But habitability does not have to depend on dryness,

Olthuis argues; on the contrary, building on water can be safer and sturdier than building on reclaimed

ground. “I think some bowls should be full,” he said, suggesting that flooding the land would amount

to little more than a natural evolution of a man-made system, not unlike the way skyscrapers

transformed cities a century ago. “It’s just an update to the machine.”

Living on the water is an old form of ingenuity, one that has often been driven by necessity. Half a

millennium ago, in what is now Peru, the indigenous Uros people used thatches of reeds to build

floating islets in Lake Titicaca, likely as a safe haven from Incan encroachment. Around thirteen

hundred people live on the islands to this day. Tonlé Sap, a lake in Cambodia, is home to thousands of

people from the country’s persecuted Vietnamese minority, who are forbidden to own property on

land. Their fishing villages, adapted to the lake’s dramatic seasonal ebbs and flows, include floating

barns, floating karaoke bars, and floating medical clinics. Olthuis has long been interested in what he

calls “wet slums,” urban waterfront areas where rudimentary wooden dwellings are often built on

stilts, as in the sprawling neighborhood of Makoko, in Lagos. “What you see is poor people adapting

to the situation,” he told me. “If they can’t find land, then they find a way to build on water. Those

people are innovators.”

Olthuis says that the Dutch approach to water management is “stuck in engineering solutions that we

already used for the last fifty years.”

Photograph by Giulio Di Sturco for The New Yorker

Olthuis likes to say that Waterstudio creates “products, not projects.” The firm’s goal is not to build

dazzlingly unique structures but, instead, to standardize and modernize floating construction with

designs that can be replicated en masse. One of Olthuis’s favorite projects to date was also the least

expensive: a prototype of a floating home made from “bamboo and cow shit” in a flood-prone area in

Bihar, one of India’s poorest states. The building had steel frames for durability, a layout that

accommodated multiple families, and an onboard stable to house farm animals in times of flooding.

Such simple structures are part of Olthuis’s concept of City Apps—“on-demand, instant solutions”

that can float into neighborhoods to add resources such as classrooms, medical clinics, and energy

facilities. He envisions persuading cities around the world to install hundreds of thousands of floating

affordable-housing units to help alleviate overcrowding and gentrification. “It’s a lifetime of trying to

connect the dots toward that future,” he said.

So far, though, most Waterstudio buildings are smaller-scale luxury products, amounting to what

Olthuis called “innovation at the cost of the rich.” One morning, I visited a floating home that

Waterstudio built on the Rhine near the city of Leiden, about twenty miles from Amsterdam. Behind a

tall, vine-covered fence was a garden with a brick pathway leading to a two-story,

two-thousandsquare-foot home with floor-to-ceiling windows and a long balcony. One of more than two hundred

floating houses that Waterstudio has completed throughout the Netherlands, it was commissioned, in

2021, by Erick van Mastrigt, a seventy-one-year-old retired Dutch financial executive, as a home for

him and his wife.

Van Mastrigt met me at the front door, dressed in a leisurely ensemble of a quarter-zip sweater and

espadrilles. “If you asked me ten years ago, ‘Me on a houseboat?’ No, I don’t think so. I never had a

plan like that,” he said. Van Mastrigt and his wife had previously lived across the street, in a

traditional home with a Dutch gabled roof, a filigreed façade, and a thousand-square-foot garden. In

2016, they bought a houseboat on the river for their adult son to stay in when he was visiting. But then

the son moved to Thailand. Tired of maintaining their large house and its landscaping, the couple

decided to downsize. The old houseboat was too small, but its site presented a possibility. They found

Waterstudio online; the house cost about 1.5 million euros to complete, a figure that Olthuis estimates

is ten or fifteen per cent higher than the cost of building a similar structure on land. The couple moved

in last year and recently sold their previous home.

In the house’s vestibule, van Mastrigt flipped a switch to open a hatch in the floor, revealing a lowceilinged

storage area, cluttered with luggage, built into the hollow of the concrete foundation. On the

main floor, an open kitchen abutted a double-height dining room. Along one side of the building was

a space, like an aquatic driveway, which in warm months houses the couple’s motorboat. I looked up

and noticed, above the dining table, a crystal chandelier mounted on a long, thick metal pillar, made

slightly less obtrusive with a coat of the same dusky-pink paint that covered the ceiling. If the

chandelier dangled only by a chain, van Mastrigt explained, it would swing with the slightest

movement of the water.

The chandelier was just one example of a conspicuous incongruity between the building’s high-tech

functionalism and the couple’s taste in décor. Down a hallway was a living room furnished with

leather armchairs and paintings of traditional Dutch interiors in gilded frames. “Many of the things we

still have here were from the old house,” Mastrigt explained. (They even keep a photo of the house on

the bedroom wall.) A tiny elevator connected to the second floor. From the upstairs balcony, the view

across the river was drably industrial: a metal-sided boat-rental warehouse, stacks of multicolored

shipping pallets, an auto-repair shop. Next door was an old, uninhabited houseboat. Like any

optimistic gentrifier, van Mastrigt chose to see the merits of his undeveloped surroundings. “You

don’t have direct neighbors,” he said. “You can make a lot of noise.”

Olthuis’s career is a union of his matrilineal and patrilineal family trades. In Dutch, Olthuis means

“old house”; on his father’s side, architecture and engineering have been practiced for five

generations. In The Hague, tile mosaics on the façades of several Art Nouveau buildings bear the

name of the architect who designed them: Jan Olthuis, Koen’s great-great-grandfather. On his

mother’s side, the family name is Boot, Dutch for “boat.” Olthuis’s maternal grandfather, Jacobus,

was the third in a line of Boots to run a shipyard in the village of Woubrugge. A tinkering streak runs

in the family: in the nineteen-fifties, Jacobus, who also had a pilot’s license, added ice runners and an

airplane wing to a boat and “sailed” the contraption over frozen ponds. I asked Olthuis how his

parents met, and he seemed surprised to recall that even this detail of his personal history had an

element of aquatic destiny: it was on a cruise around Italy.

Still, Olthuis’s path to building on water was fairly circuitous. The Netherlands is known for industrial

design, and Olthuis’s home town, Son, lies outside Eindhoven, the industry’s hub. Olthuis’s father

worked for Philips, the electronics company, in television engineering, at the time when black-andwhite

sets were being replaced by color ones. Olthuis recalls a period when the family would receive

a new experimental TV model every month, including one with a teletext printer that could spit out

sports scores and other onscreen information on a receipt-like scroll. As a child, during stays with his

grandparents, Olthuis would spend hours in Jacobus’s home workshop, building model boats, cars,

and helicopters. When he was thirteen, he began helping a friend who repaired motorbikes, which

they rode up and down country roads before they were old enough to legally drive. He worked for a

time at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Eindhoven, washing dishes and parking cars, and considered a

career in hospitality. But, when his girlfriend at the time decided to study architecture at the Delft

University of Technology, he followed her there and enrolled in the same program.

Olthuis’s student days, in the early nineties, coincided with the rise of “starchitects,” global buildercelebrities

who imprinted their projects with dramatic aesthetic signatures. Rem Koolhaas, a fellowDutchman who

founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, had become known for his conceptual rigor and his

audaciously cantilevered designs, including the wave-shaped Nexus World Housing, in Fukuoka,

and the Maison à Bordeaux, a private residence in France equipped with a giant elevator platform to carry

its wheelchair-bound owner between floors. Olthuis told me that he found

the starchitectural approach unappealingly ego-driven. “They’re more focussed on building a statue

for themselves than for society,” he said. During a university conference, though, he found himself

serving as a chauffeur for the famous Polish American architect Daniel Libeskind, and the two formed

a connection. Libeskind made Olthuis a sketch that he’s kept to this day, of a windmill in a landscape

that they’d driven through. (A fan of numerology, Libeskind also calculated that Olthuis’s career

would peak in 2031. “I’ve still got some time left,” Olthuis joked to me.) Olthuis admired Libeskind’s

spirit of experimentation, and the sense of social meaning with which he imbued projects such as the

Jewish Museum in Berlin. “He taught me that architecture could be about more than just the

buildings,” Olthuis said.

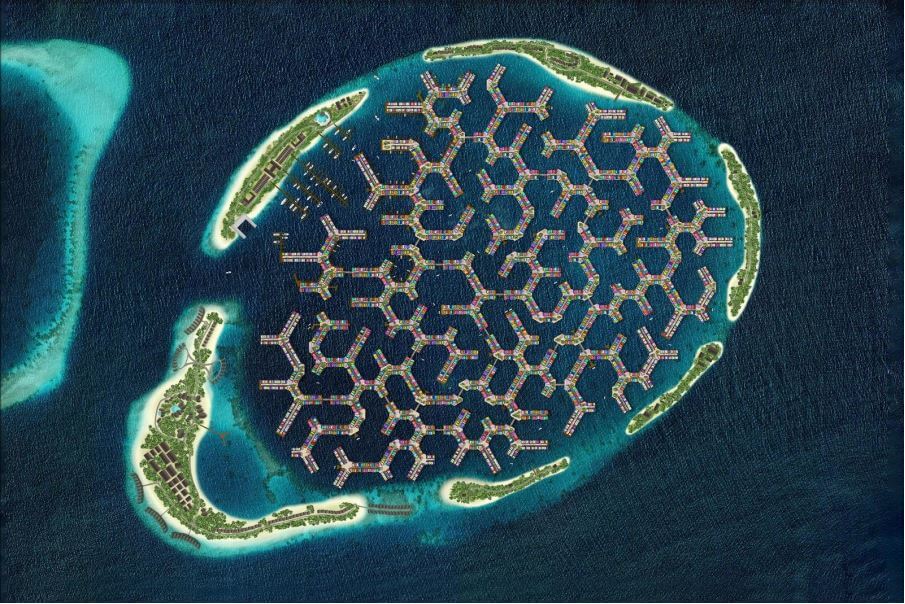

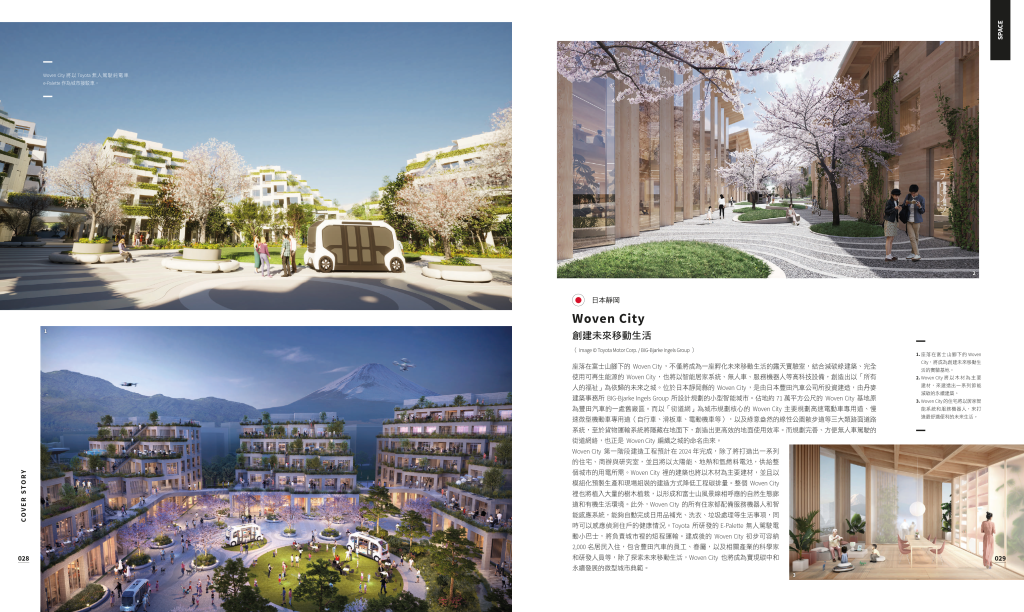

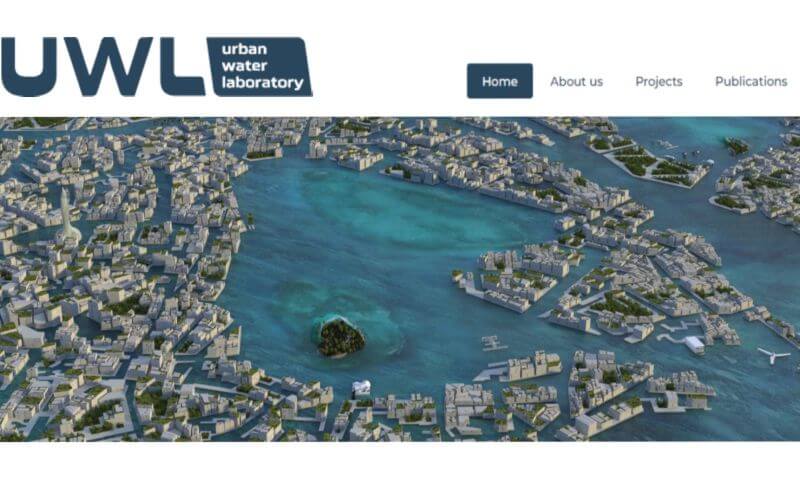

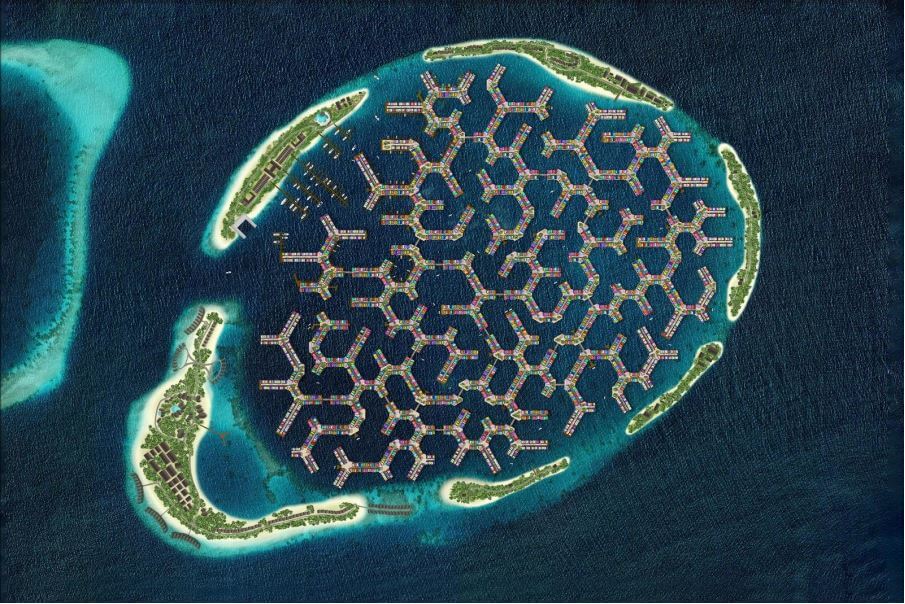

Waterstudio renderings like this one, of a floating “city” in the Maldives, are created using tools including Photoshop and the A.I. program Midjourney.Art

work courtesy Waterstudio / Dutch Docklands

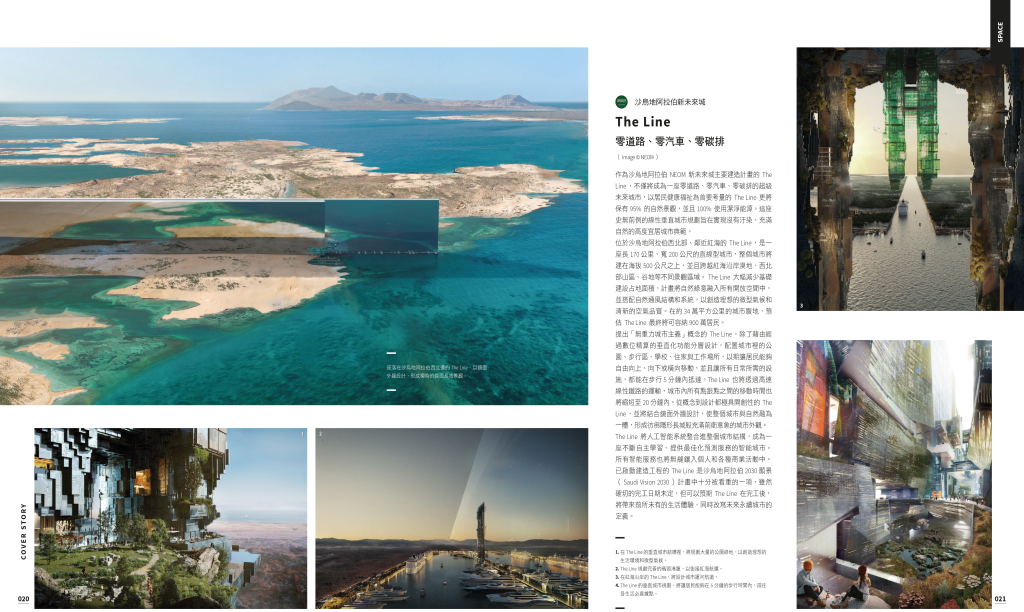

A rendering of a floating forest in the Persian Gulf, devised as part of a strategy to combat heat and humidity. When building projects on the water,

Olthuis says, “you have to be very, very patient.”Art work courtesy Waterstudio

After graduating, Olthuis got a job at a large architecture firm run by one of his former professors. For

his first project, a traffic-control center in Wolfheze, he had an initial flirtation with architecture on

the water, designing a structure that would be raised up on a plinth above a shallow artificial pond.

But he found the firm’s corporate culture stultifying. “There was not that much spirit among young

architects that you could change the world,” he said. An engineering student from the Delft University

of Technology, Rolf Peters, was working for a company that was entering a competition to design a

master plan for IJburg, a new Amsterdam neighborhood built on artificial islands rising out of IJmeer

lake. Olthuis joined the team, and, though their entry didn’t win, he and Peters decided to work

together again to devise housing for the neighborhood.

The winning plan designated plots for houseboats but had no specifications about what kinds of

structures would fill them. In the Netherlands, a houseboat is sold along with the rights to its site on

the water, just as a traditional house is legally attached to the plot of land it sits upon. For decades,

houseboats have lined Amsterdam’s downtown canals. “When you walk through them, your head

touches the ceiling, it’s damp, it’s low, it’s unstable,” Olthuis said. “But they were on the best

locations, so we thought—maybe it was youthful enthusiasm—we can do better.” They also saw a

business opportunity. On land, many young architects were competing to build in limited space. On

the water, Olthuis said, they would be “the king with one eye in the land of the blind.” Waterstudio

launched out of Peters’s home, in Haarlem, in 2003.

The firm’s first breakthrough came the following year, with the design of a glass-walled houseboat for

a wealthy family in the tulip trade. Called the Watervilla Aalsmeer, the home would be anchored on a

lake near the warehouses where flower auctions are held. According to building regulations at the

time, the size of the new structure had to match that of the traditional one-story houseboat it was

replacing. But Olthuis and Peters discovered that there were no restrictions on building beneath the

water. Their design had a footprint of more than two thousand square feet and incorporated flashy

features such as wardrobes that lowered into the concrete foundation at the touch of a button, like

weapon caches in a supervillain’s lair, and a windowless underwater home theatre with seating for

twenty. The building became a local media sensation. “We had six or seven camera crews in one

house,” Olthuis recalled. One television segment featured Olthuis, then clean-shaven and in his early

thirties, perching on a plush white sofa in the living room. He recalls telling people at the time, in

retrospect too bullishly, “In 2010, we will see floating cities all over the world.”

For the homes in IJburg, the city of Amsterdam decided that developers should follow housing codes

rather than shipbuilding ones. Floating buildings would be required to have proper insulation and

sewage systems that connected to the city’s infrastructure; they would also be allowed to rise two

stories above the water. Prospective residents could enter a lottery to buy water plots in the

neighborhood. In 2008, Waterstudio became the first firm to place a floating home in IJburg. The

structure, which is still docked in its original location, has three stories, with bedrooms built into the

foundation. When it was first craned into the water, it sank twenty-five centimetres deeper than

regulations allowed. (The homeowner later won a lawsuit against one of the contractors for making

the structure heavier than it was designed to be.) The team solved the problem by creating inflatable

jetties, filled with air and water, that formed a walkway around the building and lifted it back up.

Olthuis told me, “From then on, we could use these systems in all our projects.”

Waterstudio’s IJburg home provided the template for a new generation of water houses in the

Netherlands. Today, there are more than twenty floating neighborhoods throughout the country. The

homes in IJburg are arranged in a grid resembling miniature city blocks, with narrow docks in lieu of

sidewalks. At night, the houses glow like lanterns against the dark water. Buying into the

neighborhood has proved a worthy investment: the houses were built for around three hundred

thousand euros apiece and now sell for several times that. During my stay in Amsterdam, I rented a

room in a B. and B. in IJburg called La Corte Sconta, run by a pair of siblings from another city of

water, Venice. The rental bedrooms are on the bottom of three levels, below an open-plan kitchen and

a cozy plant-filled common area with wide sliding windows that look onto the water. When I

descended the stairs and entered my room, at one end of a short hallway, I noticed that the windows

were small and high on the wall, like they would be in an English basement. Peering out, I saw that

the surface of the lake rose right up to the bottom of the window, which meant that the floor I was

standing on was some six feet underwater. One of the siblings, Auro Cavalcante, who lives on the top

floor, told me that he only feels the building moving when there’s a storm. The weather that night was

clear, but I felt a slight wobbliness, or perhaps merely a psychosomatic case of sea legs, as I

contemplated the lake surrounding me, pushing in from all sides.

Today, Waterstudio’s headquarters are situated in a former grocery store on a quiet residential street

in Rijswijk, a small suburb halfway between The Hague and Delft. Olthuis lives ten minutes away, in

a new neighborhood built over a train hub in Delft’s downtown. Somewhat contrary to his ideal of

modest water-bound designs, he told me that he would move his family to a floating home only if he

could acquire a plot of water large enough to accommodate a yard. (When I asked his wife, Charlotte,

a chef, if she would be amenable to water living, she said, “I would like that, but maybe only for

summer holidays.”) The firm’s office space, easily visible through its large storefront windows, is

small and open, with rows of white tables where employees work. When I arrived one weekday

morning, Olthuis was in the middle of his ramen breakfast. He saw me coming and greeted me at the

door. “The street and the building are almost one,” he said.

Inside, a row of metal shelves running the length of the space was stacked with 3-D-printed models of

projects ranging from the already built to the wholly theoretical: a floating hotel with a glass roof, to

allow viewings of the northern lights; a spindly tower resembling a vertiginous stack of plates, meant

as an artificial water-based habitat for plants and animals; a “seapod” mounted, like a lollipop, on a

single pole sticking out of the water, with a home inside. Olthuis encourages an improvisatory

approach to designs and materials. He had recently discovered that a recycling company was being

paid to dispose of the worn-out blades of wind turbines, which are often buried in landfills. He and a

Korean client were discussing the possibility of reusing the hollow fibreglass pieces as foundations

for floating walkways, or, perhaps, as single hotel rooms, with windows cut into the sides. The blades

would offer “architecture that we never could have made if we had to pay for it,” Olthuis said. Such

resourcefulness extends to the use of new technologies. At one desk, Anna Vendemia, an Italian who

has worked at Waterstudio since 2018, was sitting in front of a pair of monitors and using the

artificial-intelligence tool Midjourney to generate renderings of a clamshell-shaped floating hotel

suite, with curving glass windows and an onboard swimming pool, for a client in Dubai.

One row over, Sridhar Subramani, who joined the firm from Mumbai seven years ago, was working

on a study commissioned by the city of Rotterdam. Home to the largest port in Europe, Rotterdam is

situated on the Nieuwe Waterweg, a broad canal that forms the artificial mouth of the Rhone, flowing

out to the North Sea. This position makes Rotterdam particularly vulnerable to flooding, and the local

government has invested heavily in adaptive design. In 2019, a floating solar-powered dairy farm with

a cheese-making facility on its bottom level opened in the city. The study conducted by Waterstudio

was meant to show how a theoretical fleet of mobile floating structures could change locations

throughout the day to accommodate city dwellers’ routines. In one concept, the platforms represented

restaurants that could float to downtown office buildings during lunchtime and then move to

residential neighborhoods in the evening. On Subramani’s computer screen, tiny building icons

migrated around the Nieuwe Maas river in downtown Rotterdam like a swarm of worker bees.

Subramani has an architecture degree but describes himself as an “urban technologist and researcher.”

Olthuis later told me, “Sridhar is more crazy than I am.” When Olthuis interviewed him for a job and

asked why he wanted to make floating buildings, Subramani answered that his real goal was to make

cities that float in the air, with the help of helium balloons. Rolf Peters, Waterstudio’s co-founder, left

in 2010 to pursue independent projects. For the past decade, Olthuis’s partner at the firm has been

Ankie Stam, a forty-four-year-old architect who handles the administrative and marketing sides of the

business. “We always attract people who are different than the regular architecture students,” Stam

told me as she assembled a plate of dark bread, Nutella, and sliced Gouda. “We don’t want to make

just one very nice, beautiful building.”

Scattered around the office, like loose Lego bricks, were tiny 3-D-printed models of houses from the

Maldives Floating City. On a tabletop, Olthuis unrolled an enormous sheet of glossy printer paper. It

was an aerial rendering of the finished project: a tessellated network of water-bound platforms, like a

man-made spiderweb, featuring rows of pastel-colored town houses. Estimated to cost a billion

dollars, the development will be situated a fifteen-minute boat ride from the overcrowded capital of

Malé. The complex will provide as many as thirteen thousand units of housing, which will rest in a

shallow lagoon ringed by reinforced sandbars and coral reefs designed to break waves.

For the Maldives, an archipelagic country in the Indian Ocean, climate change already poses an

existential threat. According to geological surveys, eighty per cent of the country could be

uninhabitable by 2050. The idea for the floating city originated after the Maldivian President,

Mohamed Nasheed, held a stunt cabinet meeting underwater, in scuba gear, in 2009, to promote

awareness of the potential effects of climate change on the country. The Dutch consulate in the

Maldives, drawing on the Netherlands’ international reputation in water-management technology,

connected Nasheed to Waterstudio. “In the Maldives, we cannot stop the waves, but we can rise with

them,” Nasheed has said of the project. But he left office in 2012, and since then Waterstudio has had

to navigate four different Maldivian administrations, persuading each of the project’s importance in

turn. “It’s a kind of education,” Olthuis said. “You have to start from zero.”

A first batch of four houses for the city was recently towed out into the ocean, and Olthuis estimated

that construction would be completed by 2028. “It could be faster,” he said, adding that, because the

homes are modular, multiple factories can be involved in manufacturing them at once. But previous

projects have been delayed by zoning trouble, waffling developers, and poor local infrastructure. In

2016, the Times reported that ambitious Waterstudio projects in New Jersey and Dubai were

scheduled to roll out their first units within a year. Eight years later, Olthuis described both as still

awaiting construction. Waterstudio has produced fifteen design iterations for the New Jersey project.

“This business is different than building on land,” he said. “You have to be very, very patient.”

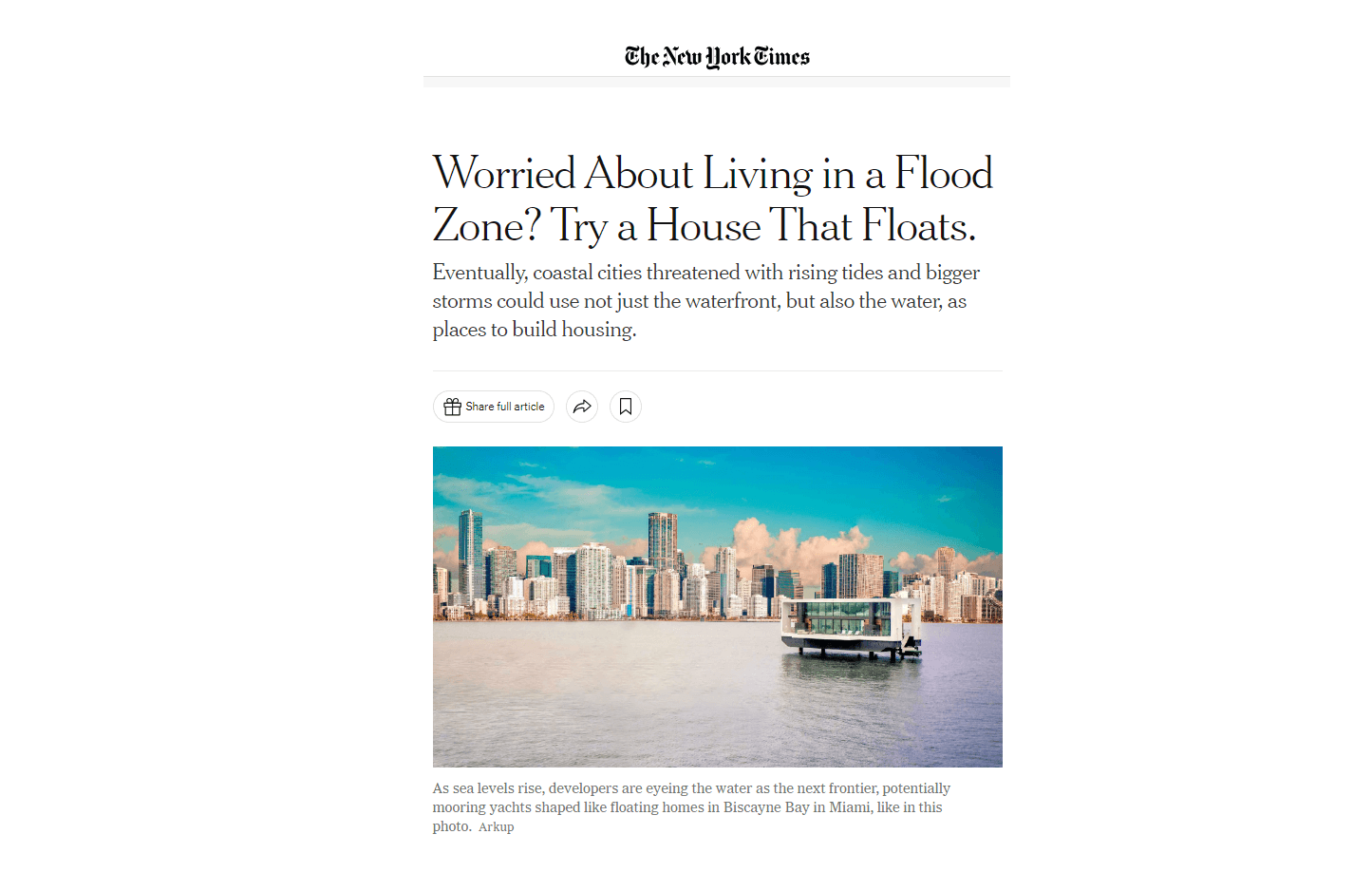

Other firms have followed Waterstudio into floating real estate. The bulk of the Maldives project is

being funded by Dutch Docklands, a commercial developer focussed on floating construction, which

will supplement the affordable housing with its own luxury floating hotels and homes. (Olthuis is a

minor stakeholder in the firm.) In 2021, Oceanix, a New York-based company, and BIG, a firm owned

by the Danish starchitect Bjarke Ingels, announced plans to build a floating development off the coast

of Busan, South Korea. Oceanix touted the project as “trailblazing a new industry,” and trade blogs

reported an estimated completion date of 2025, but as of now construction has yet to begin.

(Oceanix’s co-founder and C.E.O., Itai Madamombe, said that it would likely start by the end of this

year.)

Olthuis told me that, as competition from other, bigger firms has grown, Waterstudio has had to

engage in a “little bit of a fight” for new jobs. “Our advantage is that we have twenty years of

experience,” he said, “so we know a bit more the tricks and the problems, and that will keep us ahead

of other people for the next three to five years.” Any attention brought to floating architecture is a

good thing, in his opinion, so long as firms can deliver on their splashy promises. “There are not that

many projects, and each of these projects has to succeed,” he said.

The most devastating natural catastrophe in modern Dutch history was the North Sea flood of 1953.

Known as the Watersnoodramp, it resulted from an intense windstorm over the ocean meeting high

spring tides. Residents in the north of the country were awoken in the middle of the night, on

February 1st, by an initial deluge that inundated densely settled islands and filled carefully maintained

polders. Railways flooded and telephone poles were destroyed, cutting off communication to the

region. An official alert did not reach residents until 8 A.M., by which time many were stranded in

their attics or on their roofs. “It was as if we were spectators as the world ended,” one witness in the

village of Kruiningen recalled. The next day, at 4 P.M., another wave of water came, even higher than

the first, and destroyed many of the structures that still stood. Some survivors waited days for large

ships to reach the area. In all, nearly two thousand people died.

The disaster forced the Dutch government to confront the inadequacy of its aging dike system. Just

weeks after the flood, a committee was formed to develop a national water-defense plan, which

became known as the Delta Works, involving more than twenty thousand kilometres of new seawalls,

dikes, and dams. Its crowning element, completed in 1998, was the Maeslantkering, a hulking steel

storm-surge barrier separating the Nieuwe Waterweg canal from the North Sea.

One afternoon, Olthuis drove me through the countryside to the Maeslantkering. Outside Dutch city

centers, the artificiality of the landscape becomes harder to ignore. The roads were the highest point in

the topography; from the car’s passenger window, I could see down into farm fields below, which

were dotted with pools of water from recent storms. Small canals traversed the uneven ground in

straight lines. The land rose as we moved toward the coast—the lip on a giant bowl of kung-pao

chicken—which created the strange sensation of looking upward to see the surface of the sea. Many

of the canals running through the farmland were fortified with low hillocks covered in grass. “It takes

almost nothing to break these,” Olthuis said of the barriers. “Don’t talk to terrorists, because if you

want to screw up this country you only have to break a few dikes and then the whole system breaks.

From here on half of Amsterdam will flood.”

The Nieuwe Waterweg was crowded with industrial ships and oil rigs heading out to sea. Wind

turbines lined both shores. Olthuis pulled into a parking lot that looked out onto the Maeslantkering,

which the architecture critic Michael Kimmelman has called “one of modern Europe’s lesser-known

marvels.” Among the largest moving structures ever built, it is composed of two identical white steel

frames, each weighing close to seven thousand tons, situated on opposite banks of the canal. A

computer system tracks the levels of the Nieuwe Waterweg; if the water rises too high, the system

activates and the two frames rotate from either bank, ferrying sections of curved steel wall that meet

in the middle and seal the canal from the surging sea.

Olthuis and I walked up to a metal fence plastered with warning signs. The closest part of the steel

frames stood a dozen yards away. Their trussing often earns them comparisons to the Eiffel Tower—

they are only slightly shorter—but to me they looked more like a roller coaster turned on its side.

Standing dwarfed beside them, I felt a heady, slightly ominous thrill.

The Maeslantkering is designed to withstand the kinds of storms that are projected to happen only

once every ten thousand years. So far, outside of test runs, it has been activated on just one occasion,

in December of last year, during Storm Pia. But Harold van Waveren, the flood-risk-management

expert at Rijkswaterstaat, told me that, if severe storms grow more frequent and the Maeslantkering

stays closed for too long, the river water that would otherwise flow out to sea would have no outlet

and might flood the region regardless. “We need a whole spectrum of solutions, from very small scale

to large scale,” he said. The country has taken steps toward creating more capacity for water, as

Olthuis envisions. The so-called Room for the River project, completed between 2006 and 2021,

deepened and widened stretches of rivers at thirty locations and replaced some artificial banks with

sections of wetland landscape. Still, van Waveren seemed skeptical that floating architecture was the

future. “I’m not sure if it’s possible on a large scale,” he said.

Jeroen Aerts, the head of the department of Water and Climate Risk at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

and one of the country’s leading environmental researchers, was even more dubious. “Will there be

large floating cities? I don’t see this happening, to be honest,” he said. Living on water “is not in the

culture of Dutch people,” he continued. “On average, a Dutch person, you want to have a garden, you

want two floors.” Olthuis agrees, in a fashion. The biggest obstacles to large-scale waterborne

construction are not technological or financial, he said, but attitudinal. A NIMBYism can set in when

you ask Dutch people to imagine a wetter way of living. “They like it, but not in their back yard,”

Olthuis said. “If you ask them if their garden should be water, they say no.” He spoke with frustration

about the sluggishness of Dutch bureaucracy, and its reluctance to adjust its defensive posture toward

the Waterwolf. The country is “stuck in engineering solutions that we already used for the last fifty

years,” he said. New ones are urgently needed, “but the politicians are not ready.” We’d ascended a

hill to get a better view of the canal. Ships passed continuously through the open Maeslantkering. The

Netherlands’ familiarity with flooding has created paradoxical roadblocks to floating construction,

Olthuis said: “If your country is threatened by water, your legal framework doesn’t allow you to be

close to it.” Piecemeal ownership of floating structures is not allowed in the Netherlands, which

disincentivizes developers who might want to build and sell multiunit housing. Plus, the parcels of

Dutch water that are sold for houses remain limited in size, preventing the construction of taller

floating buildings, like the Waterstudio apartments in Scandinavia. “The city has to rezone this water

and then allow you to build plots of a hundred by a hundred feet,” he said. “We’ve drawn the plans

many times. We’re still waiting for the right city or town to approve.”

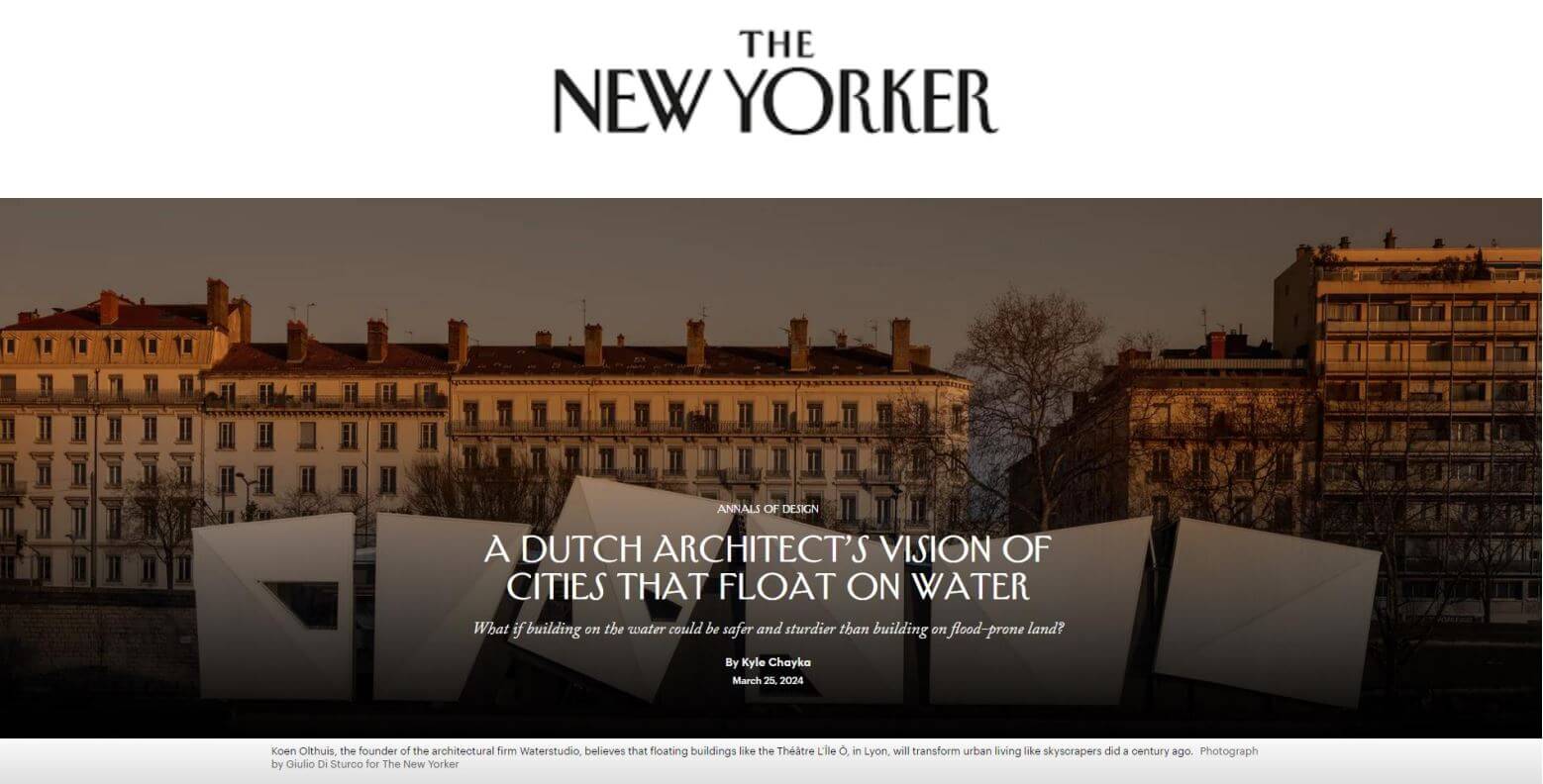

To see Waterstudio’s most ambitious completed project, I had to travel outside the Netherlands, to the

French city of Lyon. The Théâtre L’Île Ô floats in the Rhone off a paved waterside promenade near

the Gallieni bridge. (“Ô” is a homophone for eau, the French word for “water.”) On a winter

afternoon, multi-lane roads above the riverbanks roared with cars, but compared with the bustling

Dutch rivers the water on the Rhone was quiet. The theatre comprises six tilted polygons made of

white steel and cut through with irregularly shaped windows. Linked to the bank by three gangways,

it protrudes from the river like shards of an iceberg.

The building, which opened to the public in early 2023, is the second location of Patadôme, a local

organization that hosts performances for children. But Olthuis described the theatre, more loftily, as a

“global, mobile asset,” a piece of public infrastructure that, if no longer wanted in Lyon, can simply

be towed down the Rhone and docked in Avignon, perhaps, or in Marseille. Its current lease lasts

eighteen years, and its modular design makes it adaptable to different uses. David Lahille, Patadôme’s

director of business development, managed the construction project. “Today, it is a theatre,” he told

me. “Tomorrow, if we want to change it to a school, it’s easy.”

The idea for the new theatre emerged in 2018, when control over Lyon’s waterways was transferred to

the French federal government and the city launched an initiative to renew the waterfront. At the time,

Patadôme had been looking to build a new space, but construction of theatres on land remains strictly

regulated in France, owing to an old monarchic precedent dating to Louis XIV. A theatre on the water

would be exempt from that rule. “We thought about buying a ship and modifying the ship,” Lahille

said. They found Waterstudio, which suggested an ambitious new construction designed from scratch.

Among Waterstudio’s first projects was a home in Amsterdam’s IJburg, one of a number of floating neighborhoods that now exist in the

Netherlands.Photograph by Giulio Di Sturco for The New Yorker

An ebullient Frenchman with a background in engineering, Lahille recalled that, during the team’s

first meeting at Waterstudio’s office, Olthuis pulled out a box of wooden blocks, spilled them out onto

a table, and asked the clients to construct a model of the river landscape. Then he had them improvise

a shape for the theatre using the same blocks, which eventually inspired the whimsically geometric

design. “You become a child, trying to imagine,” Lahille said. Getting the project approved, though,

required bureaucratic wrangling at both the local and national level, and in the end hinged on the

enthusiasm of a single official, Jean-Bastien Gambonnet, who in 2021 was promoted to lead the local

River Navigation Unit within the French Ministry of Ecological Transition. Gambonnet hustled to get

approval from both Lyon and Paris. The process took about a year. “Here in France, usually, it’s more

than ten years,” Lahille said.

The theatre’s concrete foundation was poured five miles outside the city. The bridges over the Rhone

are unusually low, so the top floor of the building had to be constructed in situ. When the floating

platform was ready to be craned into the water, there was a question of whether the bank of the river

was strong enough to bear the weight—fifteen hundred tons in total—so the contractors rushed to

reinforce the bank in a matter of weeks, using twenty-metre-long steel piles. (Gambonnet told them

that he would smooth out the paperwork after the fact.) “I said to the port owner, ‘Now you have one

of the most powerful quays in France,’ ” Lahille said.

Walking into the theatre’s lobby, a visitor is surrounded from floor to ceiling by pale exposed beams

of cross-laminated timber, a lightweight engineered wood. When I toured the space, a children’s

production of “Animal Farm” was just letting out of the larger of two theatres, a cavernous auditorium

with two hundred and forty-four stadium seats. Long strips of bamboo created wavelike patterns on

the walls and ceiling, both for acoustics and to evoke the aquatic surroundings. Confetti dotted the

floor, and children milled about onstage, inspecting a wooden barn. The windowless space seemed far

too large to fit inside the building I’d entered, and in a sense it was: from the outside, a third of the

theatre’s height is hidden beneath the river. “Right now, you are under the water,” one of the

stagehands told me. He said that he could detect the building moving only when the occasional large

boat passed by at high speed.

When the theatre opened, some locals complained that its modern design clashed with the city’s

neoclassical stone architecture. “Very ugly,” one wrote in the comments section of a news article

about the project. “Pretentious, both in substance and in form,” another wrote. Jean-Philippe Amy, the

director of the Théâtre L’Île Ô, told me, “Lyon is a traditional city,” but added that the space has a

way of converting visitors, especially the young ones who make up Patadôme’s target audience.

Children can peek out the windows and see the current drifting by at eye level. On sunny days,

reflections of the river’s rippling surface dance on the building’s façade.

This past December, the French Alps experienced a week of heavy rains. The Rhone, which ferries

glacial meltwater down from the mountains, swelled with the excess precipitation. In the center of

Lyon, where the Rhone meets the Saone, the current strengthened. On the night of December 12th,

flooding was forecast, but the Théâtre L’Île Ô decided to forge ahead with a scheduled event hosted

by the city’s Irish consulate. The water arrived sooner and more forcefully than anticipated. To enter

the building, guests had to walk across a makeshift wooden bridge laid atop one of the gangways.

From the first-floor windows, they watched the Rhone rush by. “You could see these trees going very

fast on the flow,” Lahille recalled. He kept an eye on his phone, monitoring the river’s height, but as

the land began to flood the crowd in the theatre’s underwater auditorium remained completely dry.

When Lahille left, at 1 A.M., the water on the banks reached his knees. From land, the theatre looked

elevated, suspended on the swollen river. “The building survived, like a boat,” Lahille said. “It goes

up and down, and it’s not a problem. The only problem is leaving it.” ♦

Kyle Chayka is a staff writer for The New Yorker and the author of, most recently,

“Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture.”

click here for the pdf article of The Newyorker