By Erin Block

Travel+Leisure

Sept.2017

Photo Credits:Waterstudio

Koen Olthuis is convinced that nature always has a way of finding balance in our world: It is an equalizer and a force that can undo any disruption. The Earth is a healer and a blessing. No matter how abusive and destructive our species becomes, Mother Earth forgives and finds a way.

As the principal architect at Waterstudio.NL in the Netherlands, Olthuis constructed his vision around the collaboration of man and nature. For years, he tried to execute architecture that worked together with nature’s path instead of against it.

Now, he is among the first, along with developer Dutch Docklands, to create floating islands and homes in the Maldives that are meant for humans, but are also lifelines for the ocean and species below.

The Maldives, located in the Indian Ocean, are the lowest lying island chain and archipelago in the world — most of the country is only about three feet above sea level. It is the flattest country on Earth, and consists of 1,190 tiny islands built entirely on coral reefs. The coral reefs provide the majority of marine diversity and sustain the islands.

The islands are expected to be the first victims of climate change: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that if we don’t take action on climate change in the next five to 10 years, sea level will rise by up to four feet by the end of the century.

A nation is on the brink of extinction, but Olthuis’s philosophy is a spark in an otherwise dark maze for the Maldivian people. It’s just the beginning and it’s taken Olthuis a lifetime to get here.

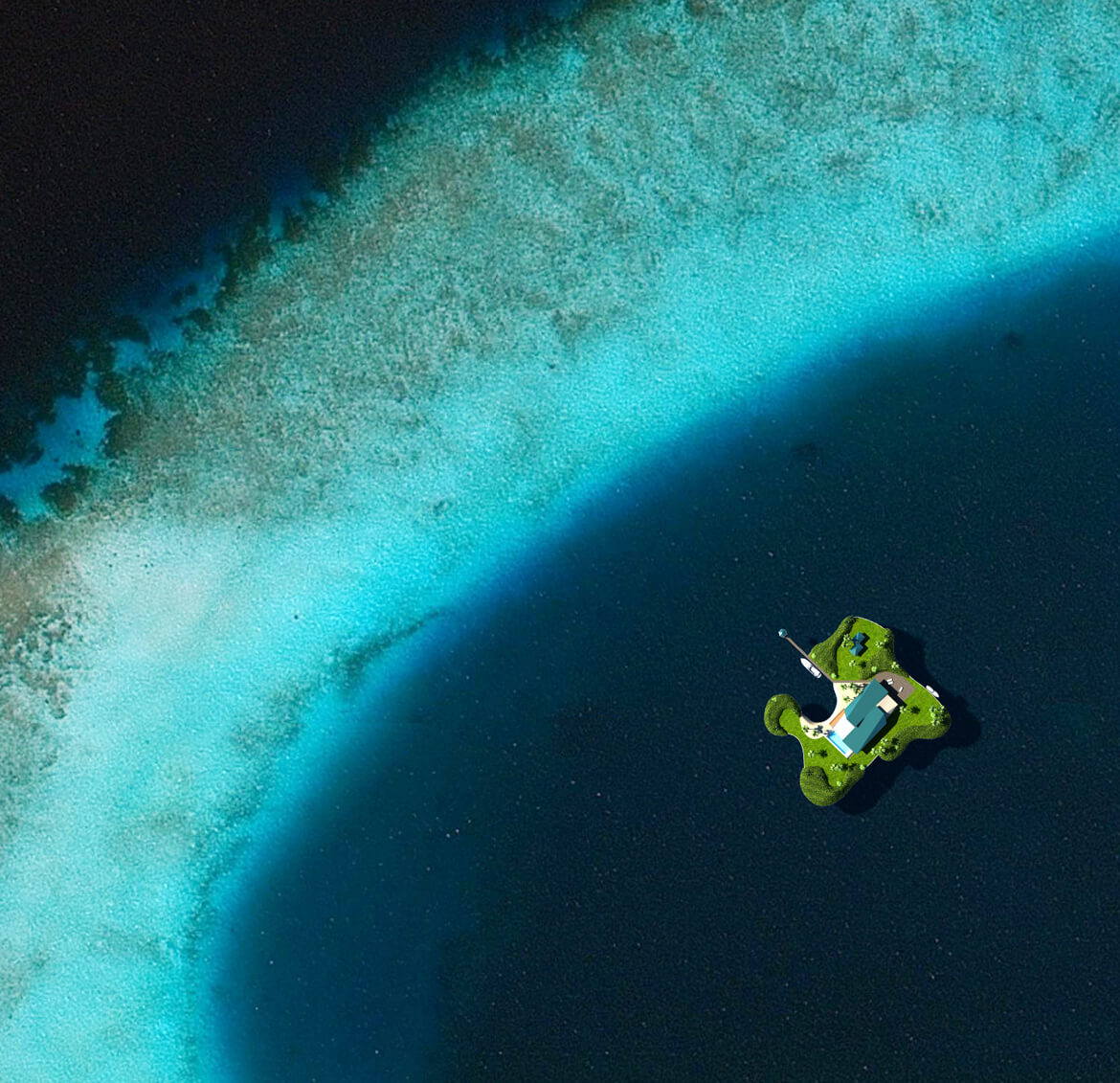

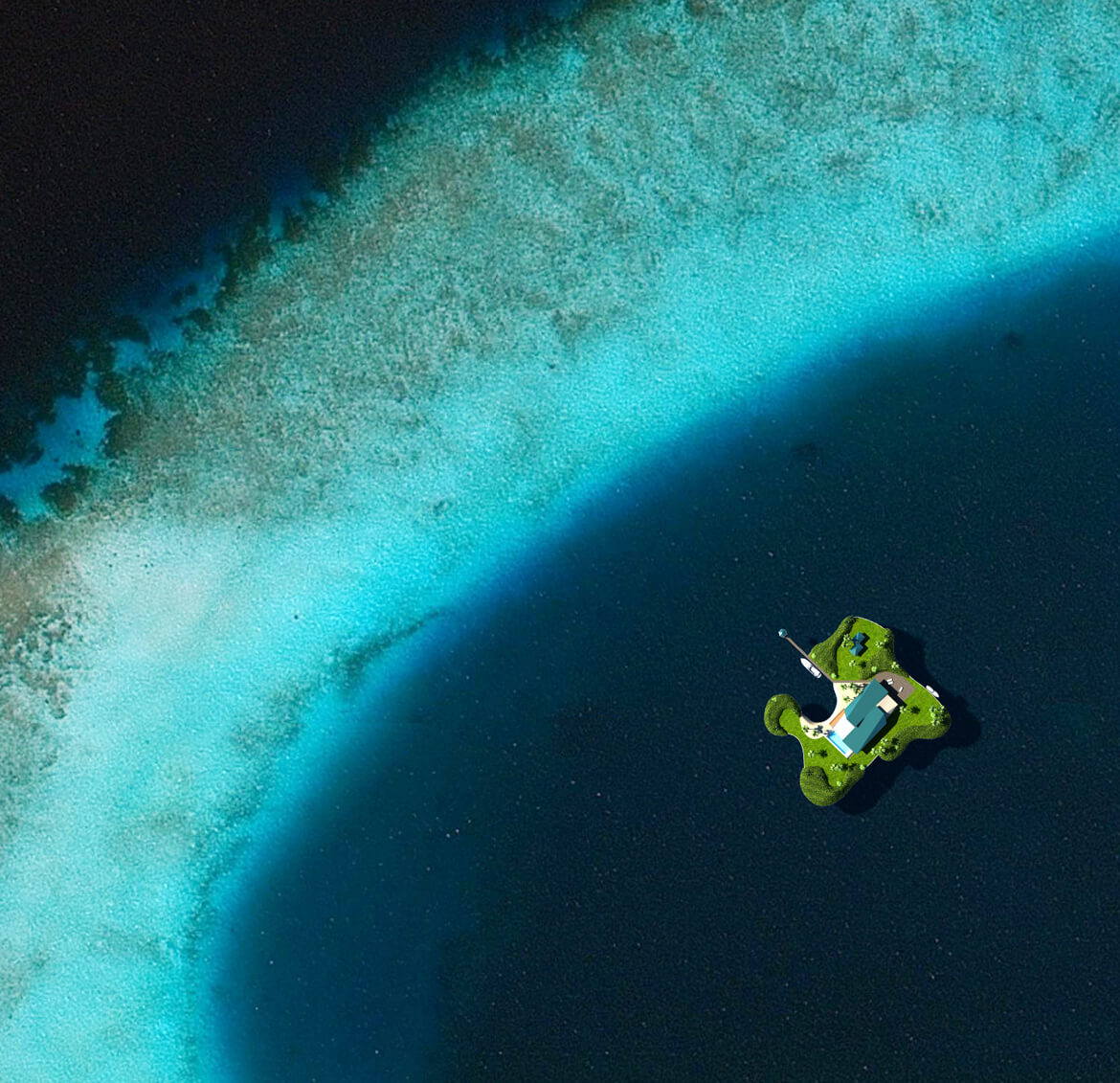

Amillarah, Floating Island, The Maldives

Courtesy of Dutch Docklands

In 2003 Olthuis, also known as the “Floating Dutchman,” was working on floating houseboats in the Netherlands. As an architecture and industrial design expert in Holland who spent his life studying the architecture of water, this was a natural progression for him. Holland has around 16,000 floating structures and, by all accounts, one of the most robust histories of floating homes. Soon, Olthuis began working on multiple boats as owners commissioned him to bolt a rigid, concrete foundation connecting the vessels to create larger and larger habitable spaces.

He spent his time learning building codes and taking in the nuances of underwater design. His designs became so glamorous and so large that he began getting attention from architecture experts and fanatics for a different type of project, man-made islands, more specifically floating islands.

Up until recently there was only one way to make an island: dredging the sea floor to create new land and coastlines. The Palm Islands, built in 2014, in the Persian Gulf off the coast of Dubai, United Arab Emirates are the most famed example of this.

The Palm Islands, though a spectacular feat of human innovation, pose significant environmental and logistical challenges. Only a few years after the Palm Islands were built, there were reports of erosion: The islands seemed to be sinking back into the water. What’s more, the maintenance of these islands could mean severe consequences for the surrounding ecosystem.

Private Watervilla, The Netherlands

Courtesy of Dutch Docklands

“Unfortunately this has dire consequences for neighboring coral reefs as it increases the turbidity of the water, buries entire habitats, and can lead to their direct, albeit incidental, removal,” said Dr. Andrew Bruckner, the director and lead scientist of Coral Reef CPR.

“The dredging also alters natural current and water circulation patterns and can cause unnecessary erosion in areas upcurrent or downcurrent from the construction site. Many islands repeat this dredging process annually as the monsoon switches direction.”

The idea of a floating island was new for Olthuis. Translating your work from houseboats to living, breathing worlds is not a step that happens overnight. The transition came in 2008: The Maldivian people elected President Mohammed Nasheed, who pledged to keep the Maldives from the threat of climate change, the rising sea levels from melting polar icecaps and a warming planet.

Nasheed had a strong message: His country is sinking. The population of almost 370,000 could either become climate change refugees, or they could be climate change innovators.

Pinpointing the moment houseboats became floating islands is hard for Olthuis to remember, but the idea of helping to continue a culture started something. He met with President Nasheed and a new era began. Building and maintaining islands that are sustainable and eco-friendly could preserve both the integrity and the livelihood of the Maldives.

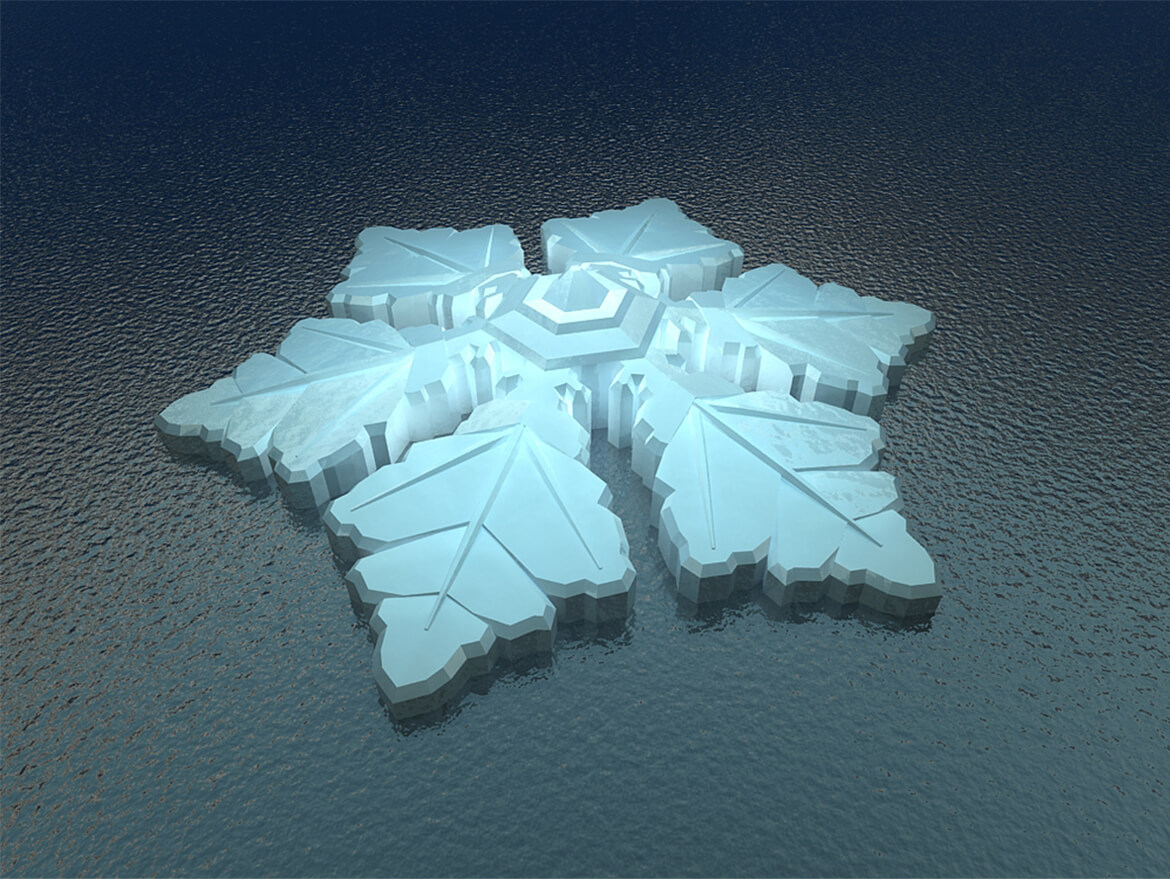

Olthuis began to work out the logistics and created a prototype that could be assembled in Holland, taken apart, shipped to a new location and then reassembled.

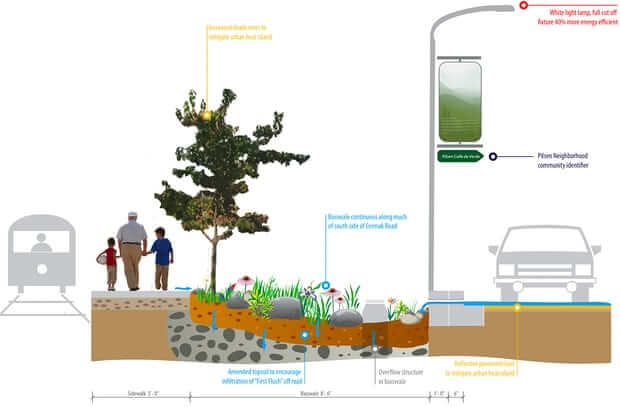

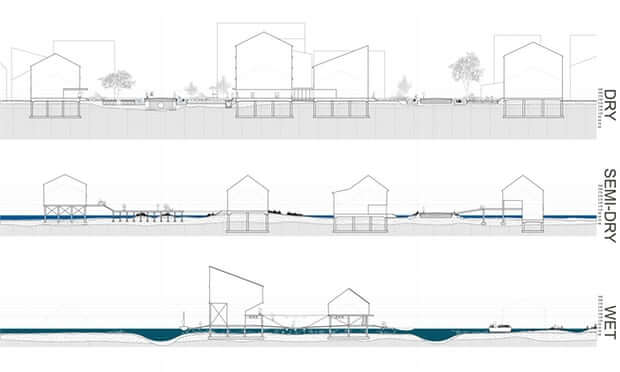

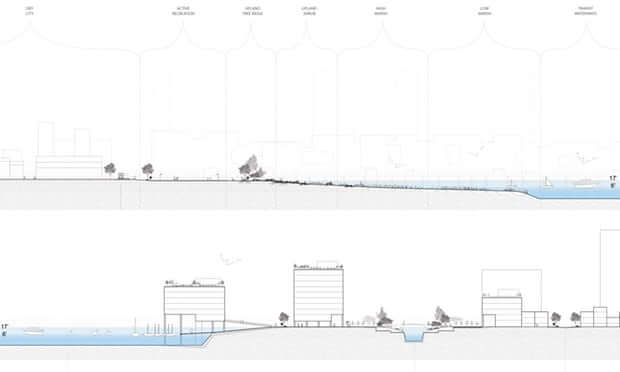

Floating islands are reassembled in underwater lagoons. The foundations can be concrete, steel or composite, depending on size and location, and are anchored with a strong cable, so they can move about a meter in each direction as needed. Though there is movement, springs are used as a stabilization tool, so standing on the surface feels as cemented as any other natural land mass. There is a flat, smooth surface underneath with no curved edges, so marine life can thrive. Through extensive research and trails, Olthuis found that round and pyramid shapes promote the most growth.

Amillarah, Private Island, The Maldives

Courtesy of Dutch Docklands

For a long time, most underwater architects focused only on the ecosystem on the surface of the island or structure. It was about making the environment as lush and as beautiful as possible, but it wasn’t the whole picture.

It took Olthuis until 2011 to realize that it was not just about the beauty of the surface — it runs deeper. Following the World Architecture Festival in Barcelona, Spain, Olthuis received a question in the audience from a journalist. Olthuis had just finished describing a new project that consisted of floating buildings with green landscapes throughout. The journalist raised his hand and asked, “Can an architect only design for people?”

This question completely changed the course of Olthuis’ life. He rethought the role of an architect, considering the responsibility and obligation to enhance the surrounding environment. His company, Waterstudio.NL, now leads with the motto, “green is good, blue is better.”

“Now, for each location you try and find out as much as possible about the current ecosystem and what you could possibly need to enhance the marine life: How to locally clean the water and what shapes make the flow of water flow naturally underneath it,” said Olthuis.

It’s about making the islands work, but not just for humans. In the past, Olthuis worked with pontoon boats in Holland to find ways to get rid of the underwater ecosystem that could chip away at the hull of a boat, but now his whole world was upside down.

“Floating islands don’t move,” said Olthuis said. “You want as much algae and shells to grow underneath these islands. We talk a lot with these experts about how they can make algae make it grow on these hulls. It’s reverse thinking.”

In August 2016, Olthuis and developer Dutch Docklands received a license to test their first island in the Maldives. They have a 100-year lease in a section of the Indian Ocean just outside the Maldivian island chain to test their floating islands. The first will be assembled and built by October 2017.

By 2019, Dutch Docklands will have invested millions of dollars and intends to have first 50 islands intact. Within the next decade, the company expects to have a total of 100 small islands.

The project was originally planned for August 2017, but, as Olthuis puts it, new clients mean new expectation. “Our clients are even more green than we are,” said Olthuis. “Our clients want to be completely off the grid. It was a challenge to make the change and develop, but we’re back on track.”

Dutch Docklands only commissioned the building of private islands known as Amillarah, which are to be sold to individuals through Christie’s in New York City. But, the technology can and should extend to create sustainable and environmentally friendly bio-reserves and new land for a culture that is sinking.

“This is just the beginning,” said Jasper Mulder, vice president of Dutch Docklands. “We will let the commercial project show that the construction can work and then work with the government to help the local community.”

If Dutch Docklands moves forward with floating islands as a social project, it is just one example of how humans, the market for luxury and sustainable products and the environment can all come to together to create a remarkable new beginning. Man may be able to have what we want and need without abusing our environment.

“In general, environmental impacts associated with the floating islands are likely to be much less severe than that associated with the continued land reclamation and dredging,” Dr. Bruckner said. “The creators behind this idea have given the environment significant forethought by placing these islands in areas that are likely to have the lowest environmental impact possible.”

Though hope for a sustainable, environmentally friendly option for the Maldivian people is strong, we still don’t know what the long-term effects will be.

“They are proposing to place these within lagoonal areas away from coral reefs. This does minimize the shading of reef systems, however it is likely to have a significant impact to these shallow lagoonal areas that provide critical nursery areas,” Dr. Bruckner continued. He is also concerned about what Dutch Docklands is proposing to do with sewage produced, as these are located within the lagoon, and discharge of sewage into the lagoon will seriously impact surrounding habitats through increased nutrients, and subsequent algal blooms. Olthuis has no concerns about the leftover sewage, however: He plans to treat the sewage water and use it promote plant and brush growth. The remaining sewage will be removed from the island on a monthly basis.

Until the floating surface is created, we won’t know its true impact on the surrounding environment, but both Dr. Bruckner and Olthuis agree that working with and for nature could be the answer.

Back in 2007, when Olthuis was not involved in the fate of this island nation, before his mission became designing islands underwater and above, he was asked to create a lush landscape and environment for Villa New Water, a residential property in Naaldwijk, The Netherlands. As a new architect and planner he believed the secret to success was to plan and organize every detail of a project. It had to be perfect.

In the midst of New Water’s production, he to visited a local friend who kept an unruly yet beautiful garden. Somehow the garden managed to heal itself through its chaotic patterns. It looked breathtaking compared to the typical residential garden, and Olthuis realized perfection was not natural — and his best work would be one guided by nature’s decisions.

To this day, the garden’s layout and idiosyncrasies stays with Olthuis. He believes nature always find an equilibrium, in spite of the human race.

“That is the point of these floating islands,” Olthuis said. “We’ll build the canvas and nature will fill it out.”

Click here to view the article at the source website

Click here to view the article in pdf