Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Mondiaal Nieuws, RENÉE DEKKER

Bouwen op water, waarom niet?

Steden worden wereldwijd steeds voller vanwege de trek naar de stad. Koen Olthuis, architect, had een eenvoudige maar revolutionaire ingeving om het gebrek aan ruimte aan te pakken: ‘Waarom niet bouwen op water?’ Speciale drijvende funderingen stelden Olthuis in staat om dit te realiseren. MO* sprak met de Nederlander over hoe bouwen op water ook kansarmen in het Zuiden ten goede kan komen.

Koen Olthuis, eigenaar van het architectenbureau Waterstudio, werd omwille van zijn FLOAT!-project door Time Magazine opgenomen in de lijst “Most influential people 2007”. Het Franse tijdschrift Terra Eco stelde in 2011 dat Olthuis één van de honderd “groene personen” is waarvan de wereld nog veel mag verwachten. Zijn passie voor drijvend bouwen leverde Olthuis ook de bijnaam “Floating Dutchman” op.

Steden zijn niet vol

Olthuis over zijn eigen idee: ‘Als architect kreeg ik regelmatig te horen dat de steden vol zijn. Daarom moet ik in steden zoals New York eerst op zoek gaan naar een pand dat gesloopt kan worden, pas dan kan de bouw van een nieuw project starten. Zo zijn we al snel drie jaar verder voordat een nieuw gebouw af is. Soms zijn de behoeftes van de stad dan al veranderd, met als gevolg dat gebouwen sneller hun houdbaarheidsdatum passeren en opnieuw gesloopt zullen worden.’ Voor dit probleem wilde Olthuis een oplossing zoeken.

De inspiratie hiervoor vond Olthuis niet ver van huis: in het dichtbevolkte Nederland is jaren aan landwinning gedaan om de bebouwbare grond uit te breiden. ‘Toch werkt dit systeem niet optimaal. Omdat een groot deel van Nederland onder de zeespiegel ligt, moet er dag in dag uit gepompt worden om het land droog te houden.’

Gewone huizen bouwen op water, het kan!

Zo kwam Olthuis op het idee om op water te bouwen. ‘Dit bestaat natuurlijk al in de vorm van woonboten. Maar dit voldoet niet aan de eisen van de meeste consumenten van vandaag. Daarom wilde ik gewone gebouwen en huizen kunnen bouwen op water.’ Hiervoor gebruikt Waterstudio een speciaal soort drijvende fundering, die zeer stabiel en veilig is. ‘Doordat negentig procent van alle grote steden op aarde in de buurt van water liggen, creëert dit heel veel nieuwe bouwruimte.’

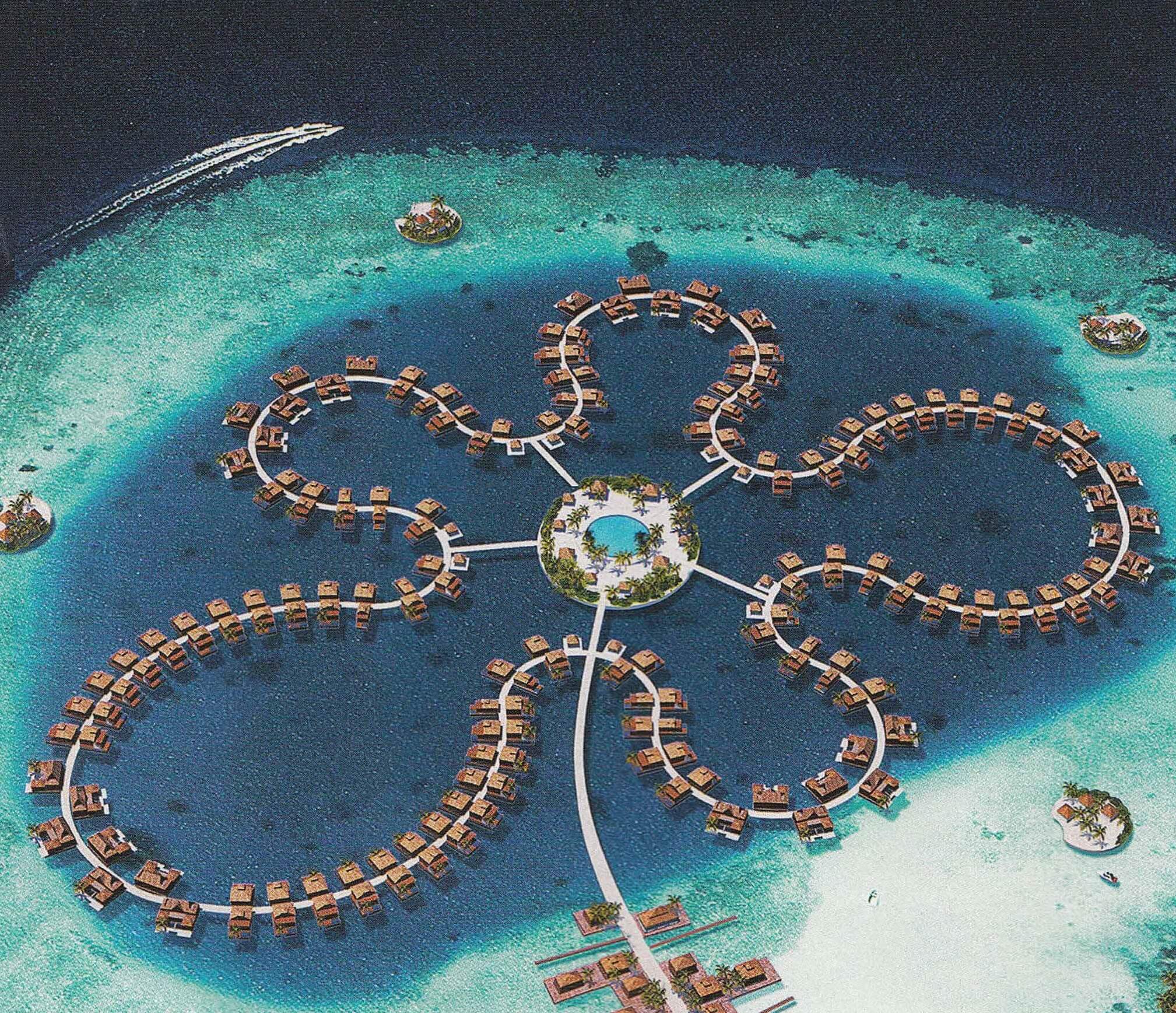

‘We moeten ook af van het idee dat gebouwen statisch zijn.’ Olthuis verwijst naar de Olympische Spelen: ‘Daarvoor wordt er iedere vier jaar een volledige stad uit de grond gestampt, maar na afloop worden die gebouwen vaak nauwelijks meer gebruikt. Zou het niet beter zijn als we eenmalig drijvende stadions en andere gebouwen konden bouwen om die vervolgens iedere vier jaar over water te verplaatsen naar een andere stad?’

Steden als smart phones

Olthuis’ project City Apps speelt hierop in. Het project ziet steden als smart phones: ze zien er aan de buitenkant allemaal ongeveer hetzelfde uit, maar toch heeft iedereen er andere applicaties op staan. ‘Zo is het ook met steden: iedere stad heeft andere behoeftes. Door drijvend te bouwen, kan men de stad constant aanpassen aan de noden, simpelweg door gebouwen te verslepen naar een andere plaats binnen de stad of zelfs een andere stad.’ Drijvend bouwen is daarom ook duurzamer: gebouwen die anders gesloopt zouden worden, kunnen een tweede leven krijgen op een andere plaats.

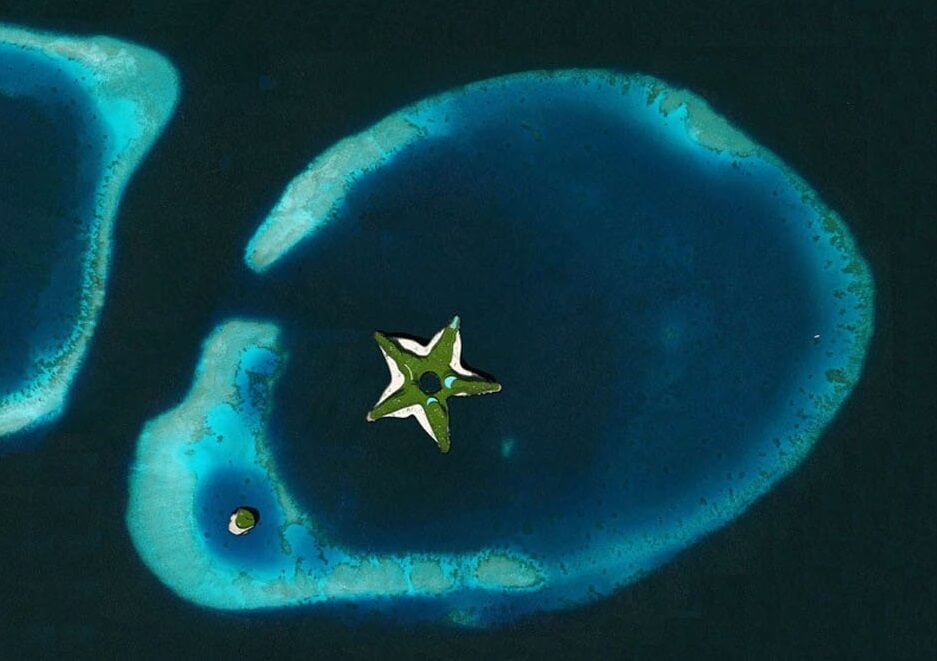

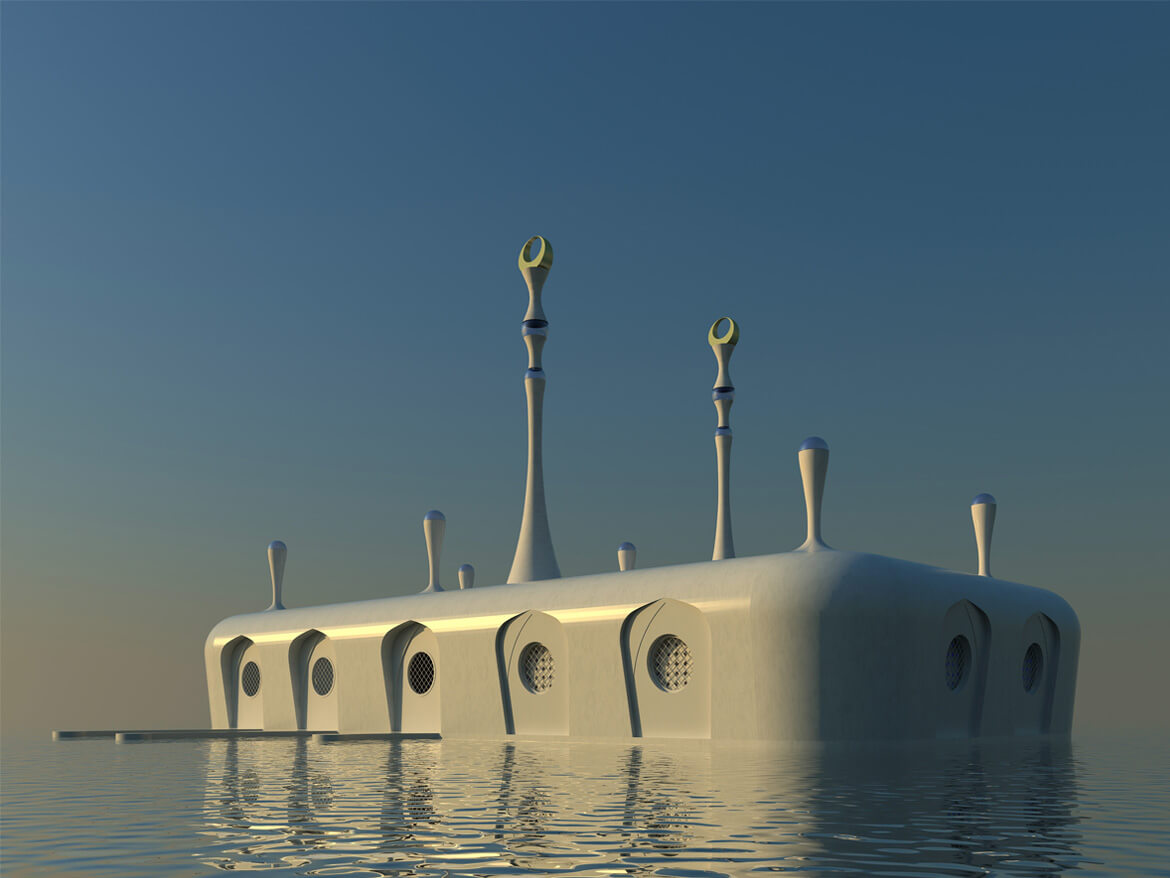

Bouwen op water is inmiddels geen toekomstmuziek meer: op dit moment lopen er drijvende bouwprojecten van Waterstudio in Miami, de Malediven en Saoedi-Arabië. Het gaat onder andere om moskeeën en luxehotels. ‘Maar mijn bedoeling met dit project was dat ook juist de armen in het Zuiden ervan zouden kunnen profiteren. Neem nu sloppenwijken, die liggen bijna altijd in gebieden nabij water, omdat niemand anders het aandurfde daar te bouwen.’

Sloppenwijken geen tijdelijk fenomeen

‘Velen gaan er van uit dat sloppenwijken tijdelijk zijn, maar dat is een misverstand. Veel sloppenwijken zijn niet erkend door de overheid, maar toch blijven ze bestaan en groeien ze zelfs. Steeds meer overheden zijn zich hiervan bewust. Ze zijn sneller geneigd om een sloppenwijk een reguliere status te verlenen wanneer er voorzieningen aanwezig zijn. Vaak ontbreken deze totaal, waardoor de wijken een onzekere status behouden’.

En juist in deze behoefte naar voorzieningen kan Olthuis’ City Apps-project voorzien: zo ontwikkelde hij drijvende sanitairblokken, zonnecollectoren, waterreinigingsinstallaties en wasruimtes, speciaal voor sloppenwijken. Op dit moment lopen er twee projecten in het Zuiden: een in de Thaise hoofdstad Bangkok en een in de Bengaalse hoofdstad Dhaka. Beide steden liggen aan het water en worden regelmatig getroffen door overstromingen.

Drijvend sanitair

Vaak is niet precies bekend waar de sloppenwijken liggen, omdat ze op geen enkele officiële kaart staan aangegeven. Olthuis wilde hierin verandering brengen: ‘Middels het wet slum-project brengen we in samenwerking met UNESCO de bestaande sloppenwijken in kaart. Daarna onderzoeken we lokaal wat er nog ontbreekt aan voorzieningen en indien mogelijk leveren we die.’ De City Apps Foundation die Olthuis oprichtte leverde in Bangkok al een sanitair blok, in Dhaka een telecommunicatie-eenheid.

Klimaatverandering zal harder toeslaan in het Zuiden, onder andere door extreem weer zoals stormen of overstromingen door overmatige regenval. Drijvende huizen zijn hier even goed of zelfs beter tegen bestand dan “gewone” huizen volgens Olthuis. Ook natuurrampen zoals aardbevingen en tsunami’s zouden drijvende huizen moeten kunnen doorstaan.

Strijd tegen klimaatverandering

‘Daarnaast bieden drijvende voorzieningen ook de mogelijkheid tot directe noodhulpverlening in geval van rampen: we kunnen bijvoorbeeld een drijvende vluchtruimte naar Bangladesh brengen als overstromingen dreigen of sanitaire voorzieningen brengen als een ramp al heeft plaatsgevonden.’ Ook voor landen die sterk getroffen zullen worden door de stijging van de zeespiegel, zoals de Malediven, kan drijvend bouwen een oplossing zijn.

Bouwen op water is nuttig in de strijd tegen klimaatverandering, want drijvend bouwen kan, net als op land bouwen duurzaam en klimaatneutraal. Zo heeft de drijvende moskee die Olthuis bouwde een airconditioningsysteem dat water benut om de binnentemperatuur te doen dalen. Drijvend bouwen is ook veel minder schadelijk voor de ecosystemen onder water dan bijvoorbeeld landwinning.

Vivre dans une maison flottante, c’est l’aventure

Le Mond, Audrey Garric, July 2013

Sur sa large terrasse arborée, Rick Uylenhoet profite de la légère brise marine. Ce pilote de ligne de 47 ans, qui passe ses journées dans les airs, a choisi de vivre sur l’eau. Il est le tout premier à s’être installé dans les maisons flottantes qui ont jeté l’ancre au cœur des îles d’Ijburg, un quartier de 20 000 habitants du sud-est d’Amsterdam (Pays-Bas).

“J’ai dessiné les plans moi-même”, lance-t-il fièrement, en faisant visiter sa spacieuse et lumineuse villa de 175 m2, sur trois étages, dans laquelle il vit avec sa femme et ses deux enfants depuis 2008. Dans son grand canapé blanc, caressant son chien, il raconte : “Ici, on a l’impression d’être toujours en vacances. L’été, les enfants se baignent devant la maison et découvrent de nombreux poissons. L’hiver, ils patinent sur le bassin. C’est fantastique de vivre sur l’eau : on s’y sent libre.”

Coût de l’embarquement : 650 000 euros pour la maison, soit 3 700 euros le mètre carré, alors que les prix peuvent grimper jusqu’à 7 000 euros dans le centre d’Amsterdam. Ce prix inclut celui de la parcelle d’eau de 160 m² (130 000 euros), donnée en concession par la ville pour une durée de cinquante ans renouvelable.

“EXPLOITER CETTE EAU QUI EST PARTOUT”

Depuis quelque temps, l’horizon de Rick Uylenhoet s’est toutefois voilé. Avec le succès de ce nouveau mode de vie, une trentaine de demeures personnalisées par des architectes ont amarré sur les pontons voisins. A quelques encâblures, de l’autre côté du bassin protégé par une digue, la municipalité a par la suite installé une soixantaine d’autres habitations flottantes, toutes identiques et moins chères.

“Amsterdam cherche à exploiter cette eau qui est partout”, explique Koen Olthuis, architecte du cabinet Waterstudio, qui a construit deux des maisons du quartier. Objectif : s’adapter à la montée du niveau des mers due au réchauffement climatique, mais, surtout, pallier le manque de place – les Pays-Bas enregistrent la deuxième plus forte densité de population d’Europe.

“Les maisons sont désormais trop proches les unes des autres. J’aimerais me sentir davantage dans la nature”, déplore le pilote, en montrant la vue plongeante sur le salon de ses voisins, à travers les immenses baies vitrées.

“AVOIR PLUS DE PLACE”

Cette proximité, Maartje Ramaekers n’en a cure. Au contraire, elle l’apprécie. La jeune femme de 35 ans, conseillère dans le domaine médical, a acheté avec son mari l’une des maisons flottantes récentes, une habitation mitoyenne cubique. “On a l’impression de vivre dans un village. On est très proches de nos voisins, avec lesquels on organise des fêtes, des barbecues, et on s’aide pour le baby-sitting”, s’enthousiasme-t-elle.

C’est pour leur fille, âgée de 2 ans, que la famille Ramaekers a élu domicile dans ce quartier d’Ijburg. “On a emménagé ici à la naissance d’Arte, pour avoir plus de place et lui faire profiter de la nature”, raconte la jeune mère alors que la petite joue dans le bac à sable installé sur la terrasse au ras de l’eau. A l’intérieur de la maison baignée de lumière, les jouets sont partout : depuis la vaste cuisine au rez-de-chaussée jusqu’aux chambres en bas, sous le niveau de la mer, en passant par le salon à l’étage, qui donne sur la terrasse où trône une balançoire. Pour ces 105 m2, le jeune couple a dû débourser 300 000 euros. Un investissement non négligeable. Mais, estiment ces amoureux de la voile, l’impression de grand large est à ce prix. “Vivre dans une maison flottante, c’est l’aventure !”

ÉQUILIBRER LES MEUBLES

Il a ainsi fallu s’habituer à dormir à 1,5 mètre sous le niveau de la mer – dans la “coque” de la maison-bateau – et au roulis en cas de grand vent. “On voit régulièrement les luminaires tanguer”, décrit Maartje Ramaekers. La maison, construite sur un caisson de béton flottant, est fixée à deux piliers solidement plantés dans l’eau, qui assurent sa stabilité tout en lui permettant de suivre le mouvement de l’onde. “Nous avons aussi dû équilibrer les poids de nos meubles avec ceux de nos voisins !”, ajoute-t-elle, en montrant son piano, disposé à l’extrémité du salon. L’hiver, le gel peut aussi s’emparer des tuyaux des arrivées d’eau, d’électricité et de gaz, qui courent sous les appontements. “On vit avec”, assure-t-elle.

Malgré l’attrait du quartier – médias et curieux s’y pressent depuis cinq ans –, certains logements n’ont pas trouvé preneur en raison de la crise économique. La municipalité projette néanmoins de construire de nouvelles habitations flottantes, plus loin vers la mer. Un nouveau quartier dans lequel Rick Uylenhoet se verrait bien emménager. En y remorquant sa maison.

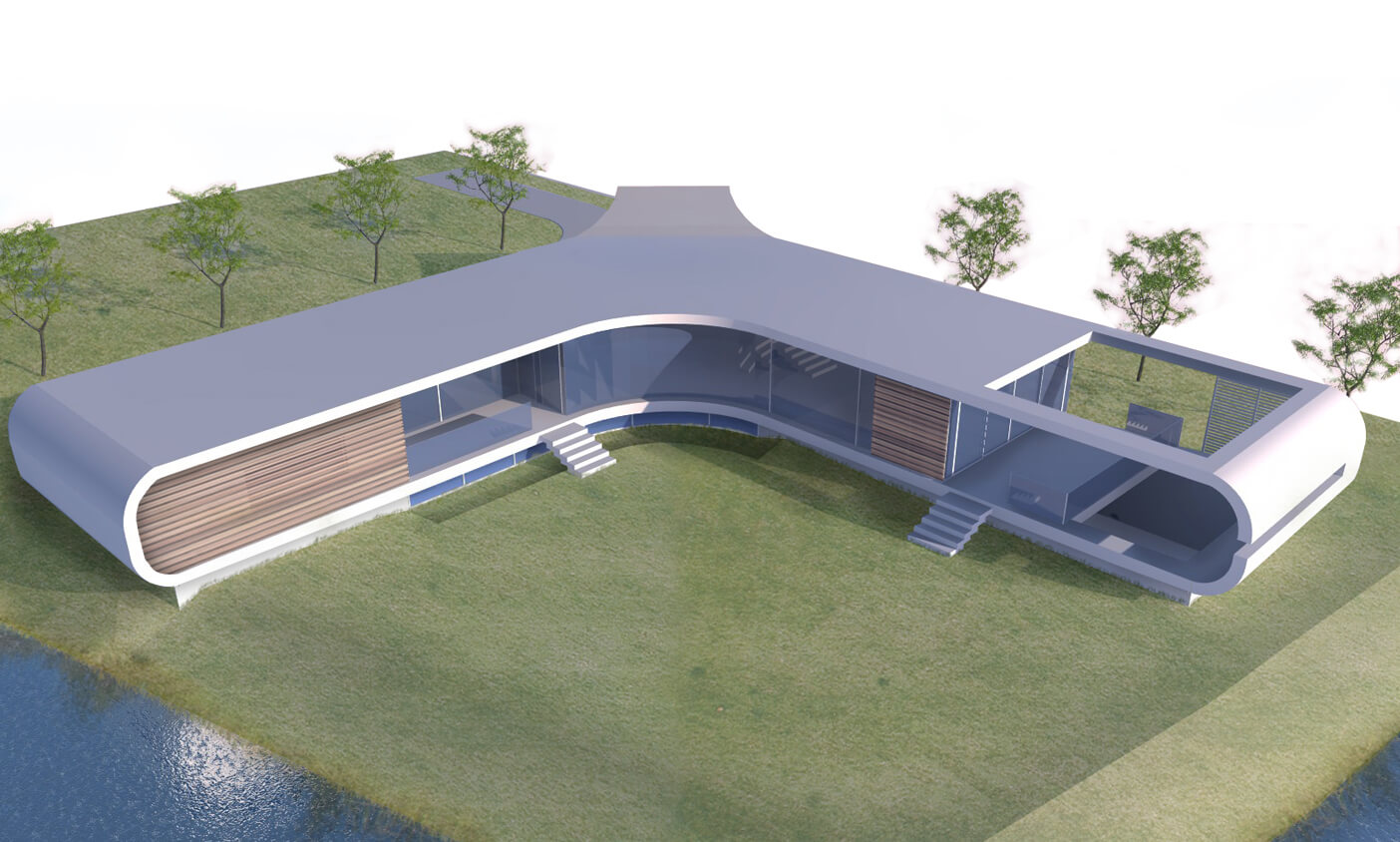

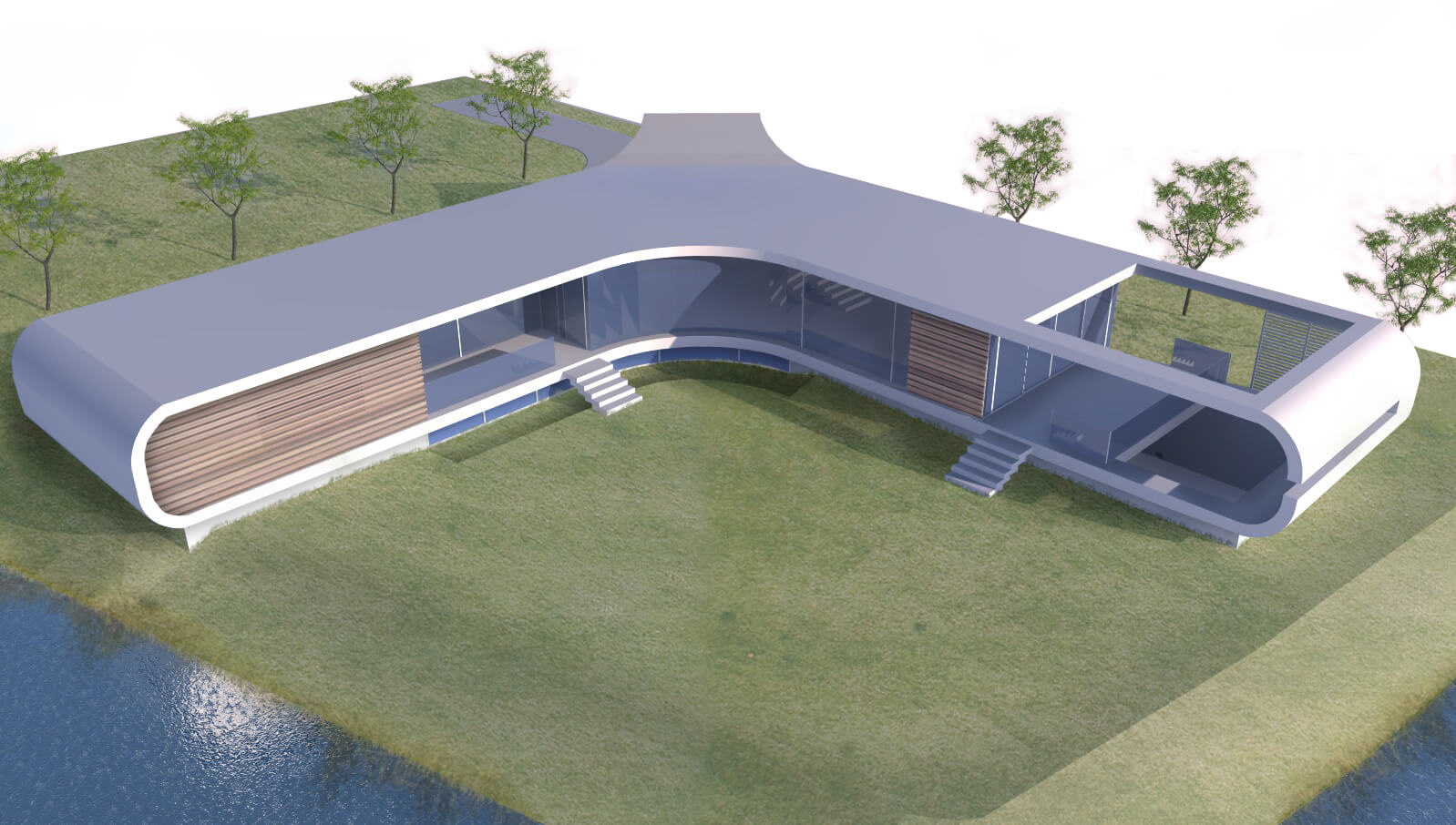

Construction Villa Naaldwijk at highest point

Construction of the villa in Naaldwijk which is part of The New Water urban plan reached its highest point.

The final shape and outlines of the villa are already recognizable.

Koen Olthuis speaks at NXT for energy and ideas

Koen Olthuis speaks at ZEVIJ NXT congress “for energy and ideas” on 13th June 2013 in Breda.

Bootbewoners Van Amsterdam

Jowi Schmitz & Friso Spoelstra, May 2013

Bootbewoners van Amsterdam Bizar maar waar: het was er nog niet, een boek over de bootbewoners van Amsterdam. Een boek waarin je naar binnen kunt kijken in die huishoudens die in de grachten dobberen. Twintig portretten in tekst en beeld. Van de eerste ‘wateryuppen’ tot de oude schippersfamilie die op een dag aanmeerde en nooit meer vertrok. Van het gezin dat jarenlang rondzwierf tot het eindelijk een ligplaats kreeg, tot de man die als student een huis bouwde op een rotte bak en er nu nog steeds woont, zonder douche en wc. Jowi Schmitz woont zelf op een schip en is gefascineerd door de verscheidenheid van al die bootmensen. Samen met fotograaf Friso Spoelstra trok ze langs zeker honderd boten om de bewoners te leren kennen. Friso spendeerde soms dagen aan boord van een schip. Jowi kreeg rondleidingen en een overvloed aan verhalen, meer dan ze op kon schrijven. Dit boek is voor iedereen met een hart voor water. En ook voor iedereen die zich afvraagt wat die mensen toch in die nattigheid te zoeken hebben. ‘Een steiger verderop zien we een schip dat wil vertrekken. Een ander schip moet ruimte maken. Eerst zit iedereen nog druk te praten en dan valt de een na de ander stil. Ten slotte zitten we met z’n allen een half uur naar die twee dansende schepen te kijken. Die schepen en verder niets. Nou, dat vind ik mooi.’ – Els Erwteman

Waterstudios villa Traverse is near completion

Villa Traverse is near completion, and the construction of another New Water Villa has started .

The construction of the first Traverse villa in The New Water is almost complete.

At this moment the facade builders are finishing the characteristic facade and the interior work will be completed this summer. On the other side of The New Water urban plan, the construction on another modern villa has started. The foundation piles are already in place and preparations on the construction of the basement floor is well ahead. The designs can easily be recognized by its modern and iconic architectural appearance.

Both villas are amongst the first that are equipped with a highly sustainable DuPont Corian facade, Waterstudio is the first office that uses this material in a large scale. It was selected by us because it is a fantastic material to use on and near the water. It also has a modern appearance, low maintenance and has the ability to thermally form the characteristic round and seamless corners of the design.

The materials used in these villas work as a test case for our water villas in the Maldives project.