Seit Jahrzehnten experimentiert der französische Architekt Jacques Rougerie mit schwimmenden Strukturen. Eine seiner bekanntesten Visionen sieht aus wie ein Rochen, der sich an die Meeresoberfläche verirrt hat – eine Stadt auf dem Wasser für 7000 Bewohner. Die Zukunft der Menschheit liegt seiner Überzeugung nach im Ozean mit seinem Potenzial als Lebensraum, Energie- und Nahrungsquelle. In seiner Cité des Mériens sollen Professoren und Studenten über einen langen Zeitraum auf dem Meer leben und dort die Artenvielfalt erkunden – autark. Die schwimmende Universität beherbergt in ihrem Zentrum eine Lagune mit Aquakulturen und einen Hafen für Expeditionsboote sowie Gewächshäuser an ihren Flügelenden.

Im Jahr 2050 werden laut Prognosen der UN 90 Prozent der größten Städte mit Überflutung zu kämpfen haben. Von den 33 heutigen Megacitys mit jeweils mehr als zehn Millionen Einwohnern befinden sich 21 an den Küsten der Weltmeere. Sie sind unmittelbar vom steigenden Meeresspiegel aufgrund des Klimawandels betroffen – und wachsen dennoch unaufhaltsam weiter, wie so viele andere, vornehmlich asiatische Küstenstädte auch.

Um Bauland zu schaffen, wird Sand ins Meer gekippt. Das hat häufig katastrophale Folgen. Wenn der natürliche Küstenschutz – zum Beispiel aus Mangroven und Korallenbänken – zerstört wird, ändert sich die Strömung und mit ihr die ganze Küstenlinie. Dazu kommt ein weiteres Problem: Sand wird knapp. Denn er wird nicht nur zur Aufschüttung von künstlichem Land verwendet, sondern ist auch Bestandteil von Beton, dem gebräuchlichsten Baumaterial. 50 Milliarden Tonnen Bausand werden jährlich verbraucht. Einige Länder Asiens wie Malaysia, Indonesien oder Vietnam haben inzwischen den Export der begehrten Ressource verboten. Die Folge: Sand wird illegal abgebaut und auf dem Schwarzmarkt gehandelt.

“Wir müssen Wasser als neuen Baugrund begreifen.”

Architekten entwickeln nun verstärkt Pläne, die Stadt neu zu erfinden und auf das Wasser auszuweichen. Sogar die Vereinten Nationen können sich schwimmende Metropolen vorstellen. Erst vergangenes Jahr hat UN-Habitat, das Wohn- und Siedlungsprogramm der Vereinten Nationen, in New York einen ersten runden Tisch zu dem Thema veranstaltet, mit Forschern und Experten des MIT Center for Ocean Engineering und Mitgliedern des Explorer Clubs. Die dänischen Architekten von BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group stellten dort Oceanix City vor, eine Blaupause für das Leben auf dem Meer, die sie zusammen mit der Firma Oceanix entworfen haben.

Die schwimmende Stadt ist aus sechseckigen Plattformen von je 20 000 Quadratmetern zusammengesetzt, die für jeweils bis zu 300 Menschen ausgelegt sind. Die Module werden am Meeresboden verankert und miteinander verbunden. So kann die Siedlung wachsen und sich an die Bedürfnisse ihrer Bewohner anpassen. Oceanix City ist als abfallfreies Kreislaufsystem konzipiert, das seine Bewohner mit Energie, Trinkwasser und Nahrung versorgen kann. Kein Gebäude ist höher als sieben Stockwerke. Dadurch bleibt der Schwerpunkt der Inseln niedrig und die Konstruktion kann auch heftigen Stürmen standhalten. Mit anderen Worten: sie kippt nicht, auch nicht bei starkem Wellengang. Sollte sich das Wetter langfristig verschlechtern, ließen sich die Module vom Meeresboden lösen und in ruhigere Gewässer transportieren.

“Wir können uns Lebensräume auf dem Wasser erschließen, ohne Meeresökosysteme zu zerstören”, sagt Marc Collins Chen, Chef von Oceanix. “Die Technik dazu ist vorhanden.” Er bezeichnet das Potenzial des Projekts vor allem in der Erweiterung bestehender Küstenstädte: “Schwimmende Siedlungen könnten die verletzlichsten Bevölkerungsgruppen schützen.”

Um die Baukosten niedrig zu halten, sollen die Oceanix-Module an Land vorgefertigt werden, die Plattformen aus Salzwasser-resistentem Spezialbeton, die Gebäude möglichst aus lokalen nachhaltigen Baumaterialien, etwa aus Bambus. Die einzelnen Module gelangen dann im Schlepptau von Schiffen an ihren Ankerplatz. Und da auf dem Meer “Baugrund” in großer Menge vorhanden ist, könnten auch die Miet- oder Kaufkosten niedrig gehalten werden. Das bedeutet: schnell erschlossener, günstiger Wohnraum, den viele Küstenmetropolen so dringend benötigen.

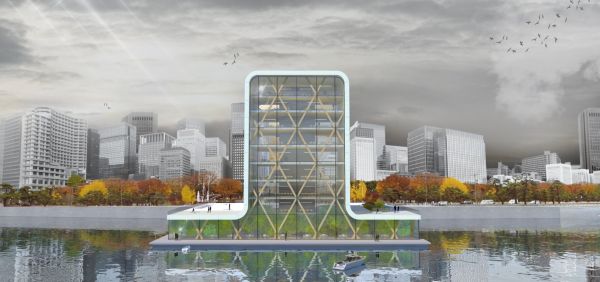

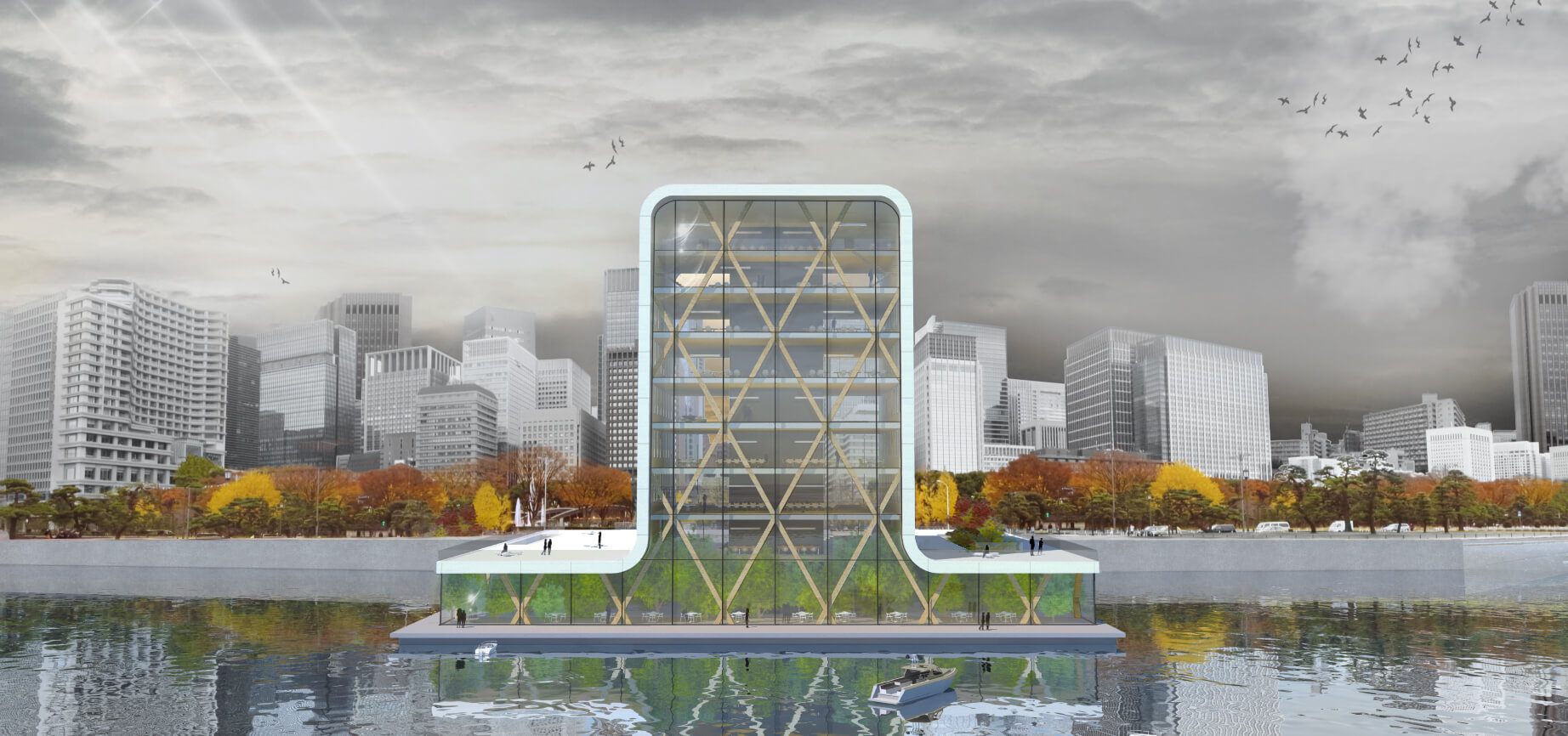

“Wir müssen Wasser als neuen Baugrund begreifen, der anders funktioniert als das Land”, sagt Koen Olthuis. Vor mehr als 15 Jahren begann der Niederländer, sich mit seinem Büro Waterstudio.NL mit dem Bauen auf dem Wasser zu beschäftigen. Inzwischen hat er verschiedenste Projekte umgesetzt – darunter zahlreiche schwimmende Einfamilienhäuser. Gerade hat er den weltweit ersten schwimmenden Turm mit einer Höhe von 40 Metern präsentiert. Er sieht die Vorteile maritimer Stadtteile in einer dynamischeren und effizienteren Urbanität. Schwimmende Gebäude könnten verschoben und temporär dorthin gebracht werden, wo sie am besten zu nutzen sind. “Eine Stadt könnte zum Beispiel ein Fußballstadion leasen. Warum sollte man viel Geld für den Bau ausgeben? Besser, man mietet es, wie ein Auto”, sagt Olthuis. Solche mobilen und flexiblen “Immobilien” könnten für Investoren interessant sein – und damit den Einstieg in den Bau schwimmender Städte auslösen.

Kleine schwimmende Communities in Küstennähe großer Städte brauchen nicht unbedingt autark zu sein. Große Metropolen auf dem Meer müssten sich allerdings zwingend selbst versorgen können, mit einem eigenen Kreislaufsystem für Strom, Wasser, Abwasser und Müll. Als brauchbare “Standorte” hat das Seasteading Institute in Kalifornien Unterwassergebirge ausgemacht. Eine Wassertiefe von nicht mehr als 250 Metern erleichtere die Verankerung am Meeresboden.

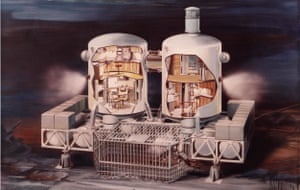

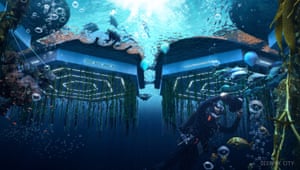

Im Gegensatz dazu macht sich die Ocean Spiral gezielt die Tiefsee zunutze. 500 Meter Durchmesser hat das mit einer Wabenstruktur verstärkte und mit Acrylglas ummantelte Kugelbauwerk für 4000 Bewohner. Der größte Teil liegt wie ein Eisberg unter Wasser. Gigantische Ballastbälle halten die Stadt im Gleichgewicht. Eine spiralförmige Konstruktion verankert sie am Meeresgrund in bis zu 4000 Meter Tiefe. Zur Energiegewinnung wird die Temperaturdifferenz zwischen der kalten Tiefsee und den wärmeren Wasserschichten weiter oben genutzt. Mikroorganismen, die am Meeresgrund leben, sollen Kohlendioxid in Methan, also ebenfalls Energie, umwandeln. Trinkwasser könnte über Umkehrosmose hergestellt werden. Dabei wird der hohe Druck in der Tiefsee zur Entsalzung des Meerwassers genutzt. Unterwasserfarmen in den oberen Meeresregionen versorgen die Bewohner mit Fisch, Krustentieren und Wasserpflanzen. Am Ende der Spirale wird auf dem Meeresgrund nach natürlichen Bodenschätzen gegraben. Was wie eine Utopie anmutet, könnte nach den Plänen der japanischen Baufirma Shimizu bereits in zehn Jahren Wirklichkeit sein.

Künstliche Inseln sind mobil. Was heißt das für die Nationalität ihrer Bewohner?

Einen anderen Ansatz verfolgt Bauingenieur Gianluca Santosuosso. In Teamarbeit mit LESS, dem Laboratory for Eco Sustainable Systems, hat er Hypercay entwickelt, eine im Meer treibende Siedlung, die sich selbst versorgt. Dank seiner beweglichen Wirbelkonstruktion kann sich das Objekt den wechselnden Strömungsverhältnissen natürlich anpassen. Sollte es nötig sein, erzeugen hydraulische Hubkolben genug Antriebskraft, um die Megastruktur wie einen Aal durch enge Passagen, in Häfen oder Buchten navigieren zu können. Das Herz des Projekts ist sein autarkes Versorgungssystem, unter anderem bestehend aus einem “Marine Garden”, wo Tiere und Pflanzen gezogen werden, Müllrecycling zur Erzeugung von Biogas und einer Meerwasser-Entsalzungsanlage. Strom wird aus Sonnen- und Wellenkraft erzeugt.

Ideen für schwimmende Städte gibt es einige. Dennoch wurde noch keine davon in die Realität umgesetzt. Hohe Kosten und Scheu vor dem Risiko dürften eine Rolle spielen. Und womöglich gibt es ein Problem mit der völkerrechtlichen Zuordnung. Denn der Staatsbegriff bezieht sich eindeutig auf das Festland und die Küsten. Das schließt zwar alle Inseln mit ein, jedoch keine freischwimmenden Konstruktionen. Aber ist eine am Meeresboden verankerte Siedlung, die wie Oceanix City an einen anderen Ort verbracht werden kann, nun eine Insel, oder muss sie als mobiles Objekt betrachtet werden? Und was passiert mit der Nationalität ihrer Bewohner bei einem Standortwechsel? Auf Schiffen in internationalen Gewässern wiederum gilt die Rechtsprechung des Landes, unter dessen Flagge sie fahren. Müsste eine freischwimmende Stadt nicht wie ein Schiff behandelt werden? Unter welcher Flagge wäre sie dann unterwegs? Am Seasteading Institute träumt man von politisch autonomen Siedlungen auf See. Das Konzept des Nationalstaats, das Staatlichkeit, Territorium und Volk als untrennbare Elemente sieht, wird infrage gestellt. “Die Welt braucht Orte, wo man experimentieren und neue Gesellschaften aufbauen kann”, heißt es in der Selbstdarstellung.

Die Vereinten Nationen scheinen sich nun jedenfalls ernsthaft mit dem Thema zu beschäftigen. Künftig soll sich ein Expertengremium regelmäßig treffen, um die konkreten nächsten Schritte für Oceanix City zu planen – und die Stadt zum Schwimmen zu bringen.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)